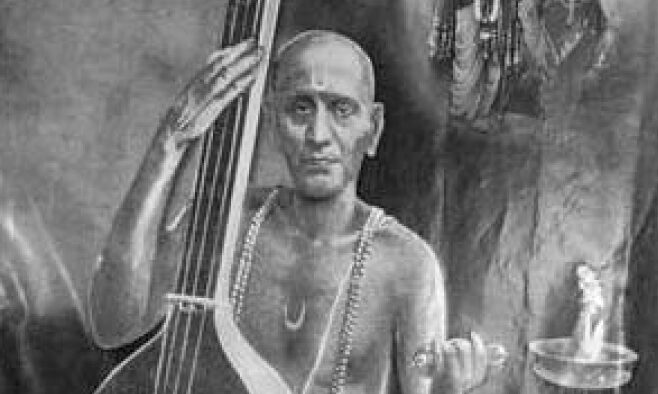

The raga is all around us. Kalyani, Shankarabharanam, Mohanam…. Their notes seem to waft in and out of our lives, elusive, yet ever present, snatches of music heard and unheard. Even those music lovers who have not been initiated into the phrasing and presentation of individual ragas are familiar with the names – as they are with the Karnatic Trinity, led by Thyagaraja (1767-1847).

The aradhana today gives us more opportunities to reflect on the colossal accomplishment and contribution of one of the world’s towering musical geniuses.

First, there is the sheer number of compositions. Legends credit him with “thousands.” Extant are around 682 krithis, with some being sung only in certain ‘sampradayas’ or lineage of disciples. The two other members of the Trinity, greats in their own right, Muthuswamy Dikshitar (1775-1835) and Shyama Sastri (1762-1827) have 380 and 70 respectively. Thyagaraja also composed some namasankirtanams, sung like bhajans in chorus and called Divyanamakirthanas, some utsava sampradyam songs and two operas Nauka Charitam and Prahalada Bhakti Vijayam.

All three of them were contemporaneous, born in the same city of Thiruvarur in houses within walking distance of each other. Before this period, saint poets like Purandharadasa and Annamacharya composed bhakthi poetry, hundreds of pieces, which were sung with ecstatic devotion in various musical modes, which evolved into the raga format. While a tradition of associating a particular song or poem with a raga developed later, it is not known if Purandharadasa actually intended them to be sung in that particular fashion, or even in that raga. For Purandharadasa and Annamacharya, the music perhaps was a vehicle to convey bhakthi, and their complete and unconditional surrender to God. Annamacharya’s krithis were not set to ragas till the early 20th century.

Purandharadhasa however is considered the father of Karnatic music, and is credited with many basic keerthanas taught even today in the beginning stages. He may have well paid more attention to the musicality of his lyrics then we may guess at today.

Be that as it may, there is no doubt that Thyagaraja ushered in a revolution. By closely integrating the raga and raga phrases into his lyrics, the sahithya, the emotion, the laya (beat) and the melody became inseparable. Research scholar Dr Lalitha Ramakrishnan puts it this way: “Thyagaraja was conscious of the inspiring quality of Karnatik ragas. All his krithis are set in the most simple everyday language, since he wanted classical music to be the mode of conversation with the supreme power…Thyagaraja’s krithis were set in easy tala structures, so that even rare ragas were assimilated and enjoyed by all.”

Musical masterpiece after masterpiece poured out in ecstatic fashion from his mouth, many, traditionalists aver, created with great spontaneity, and captured later and written down by his disciples. While that may well be true, the intricate musical phraseology and range also indicate a highly-skilled master craftsman at work, chiseling and polishing his creations to perfection.

Shankarabharanam was the raga most favoured by Thyagaraja and Muthuswamy Dikshitar, with the latter in fact composing 47 krithis to Thyagaraja’s 31. A sampoorna raga, with all seven notes used, symmetrical in the ascent and descent, it is also present in musical cultures world wide – it is the basic C major scale in Western music. Its heavy usage is perhaps a pointer not just to its appeal, but to its flexibility and range.

The next major raga is Todi, with 26 compositions by Thyagaraja. Todi is considered one of the most challenging of all ragas, with great scope for elaborate delineation and creative presentation. Sangeetha Kalanidhi R Vedavalli has written, “there are many ragas that are based on phrases or prayogas and improvising a raga alapana means elaborating and expanding these phrases. But Todi is very unique in that every swara is a jiva swara (life note) and nyasa swara (ending note). It allows the elaboration of every gamaka and every note.”

With 26 majestic compositions, Thyagaraja has unfolded every nuance of those notes, played with every phrase and every gamaka. “Many concepts like the development of the raga, kala pramana, and use of stayi are well delineated in Thyagaraja’s compositions, especially through the layers of sangati,” writes Vedavalli. She cites the examples of Endu Daginado and Varidhi. “The sangatis in these krithis also serve as lessons in effectively combining speeds while singing raga phrases.”

Todi is just one shining example of what Thyagaraja has done with the Karnatic raga, and the Karnatic composition, setting the gold standard for emotional impact and musical range in the modal form. There are over 20 ragas in which he has at least 10 compositions or more. Saveri, Kalyani, Bhairavi and Saurashtram have also received this elaborate treatment.

All three of the Trinity have magnificent compositions in the ever popular Kalyani. It is interesting that Kalyani is actually very close to Shankarabharanam, with all the notes being the same except for the ‘ma’ – suddha madhyama in Shankarabharam and prathi madhyama in Kalyani, which makes all the difference.

Those with only a passing familiarity with the Trinity’s oeuvre may in fact be surprised that these ragas are the ones most used. Where is Hindolam of Samaja Varagamana, where is Hamsadwani of Vatapi ganapatim bhaje, where is the Abheri of Nagumomu, they might wonder. The fact is that are just one or two krithis each in these ragas.

Which brings us to the other aspect of Thyagaraja’s range and contribution. Thyagaraja’s 680 krithis cover over 230 ragas. Many of the ragas, including some very popular ones, have only or two krithis composed with them. A testament to their uniqueness? Exhaustion of their possibilities in a single krithi? Lack of flexibility in providing range. May be a little bit of everything, may be just chance. But it is fact that many of these singletons or duos are absolute gems. Apart from Endaro Mahanubavulu, there is only two other in Shri Ragam – Nama Kusumamulache and Yuktamugadu. Of course Sriragam’s close associate is Madhyamavathi, in which Thyagaraja has composed 15 krithis. Nagumomu’s Abheri is the only one. And the lovely Ganamurte, one of the very few compositions in Sanskrit (sung only in some sampradayas), also stands alone in raga Ganamurthi. Then there are the popular krithis in rather unfamiliar or lesser used ragas – Brovabarama is in Bahudari and Teliya leru Rama is in Dhenuka.

Thyagaraja’s krithis show us the “nature and beginnings and development of the art of music, manifestation of the musical sound in the body, its cultivation, its role and its philosophy,’ writes the late Padmabhushan V Raghavan, whose commentaries on Thyagaraja are extensive and incisive.

Thyagaraja is also credited with fine-tuning the three-unit (pallavi, anupallavi and charanam) structure for krithis -- one can see the “rationale of the structure -- an opening idea, a development of the idea and an elaboration of the idea with other contributory ideas, similes, illustrations, and incidents that justify the landing idea of the song…When presenting feelings and mental states, his emotional pieces also follow this plan. It is paralleled by the technique of raga-development, which takes off at a characteristic or essential phrase and then is amplified somewhat and then taken to a full sweep,” writes Raghavan.

He adds: “All the earlier creative efforts led to Thyagarja and all that was created after Thyagaraja in the immediately following period or in the present century, is after his model.”

Thyagaraja’s music of course is also about spirituality and the Upanishadic search for the ultimate truth, not to mention great devotion to Lord Rama and a desire for union with that ultimate. The word Sudha Rasam has been used frequently by Thyagaraja. To him music was the path to Rama. In Raga Sudha in Andolika, he says if you sing a raga you will get moksham. In Svara Raga Sudha in Shankarabharanam he says swaram and ragam together give Bhakti. In inta saukhyamani in Kapi he adds laya as being the path to Bhakti. In Sogasuga Mrdanga in Sriranjani he says one who sings with the mridangam gets salvation. For him, the Bhakti rasa contains within itself all of the nava rasas. He even goes so far as to say if not through music, then Teliya Leru Rama Bhakti Margamunu.