Dr Sushruti Santhanam combines her musical talent with an intellectual rigour on researching Indian art forms. Based in Pune, she founded the Centre for Arts, Society and Policy (CASP) www.casp.org.in which is a practitioner-initiated space looking at how art emerges in the interaction between aesthetic need and social life. She has worked for decades with artists from all over India.

This year, Dr Sushruti has initiated district level surveys of traditional performing artists (music, dance, storytelling and ritual arts) sponsored and promoted by patron and people’s group in each district. The pilot of this project Abhilekh has been launched in Solapur district of Maharashtra.

The second project she says is “creating a consultation with artists on ideas of ownership, stakeholdership and innovation, designed as a response from traditional artists to legal frameworks of IPR and copyright.” CASP will be organising a symposium in October as part of its annual series Talking with Tradition. This year’s theme is –Traditional Knowledge and Ownership. She spoke to INDICA about her music inherited from her illustrious mother, Sangita Kalanidhi R Vedavalli and her interest in research on the Indian arts.

What are the roots of your interest in the arts that led to the setting up of CASP

I have had the opportunity of being born in a family where everything revolved around music. In later years I had the absolute privilege of working closely with traditional artists and some artisans across three states. I also found some very unique and extraordinary teachers particularly Guruji Ravindra Sharma of Adilabad and scholar of handloom and craft knowledge, Dr. Annapurna Mamidipudi who helped shape my perspective on craft and art dimensions of Indian society. I became fascinated by how knowledge moved, how it worked in producing art forms that are at once old and new, at once intimate complex thought processes and a socially evocative phenomena and how artists both conserve their aesthetics while simultaneously responding to changing contexts.

Combined with my knowledge of Carnatic music and a ring side view of the professional life of Carnatic musicians, my attention was forced onto the relationship between art and society, art as a way of knowing techniques and as a way of knowing the samaj.

I studied the works of Ananda Coomaraswamy and it helped me understand arts practice as the basis of collective identity, a collective space of catharsis, a structured space of training the mind, a deep state of spiritual evocation and a resilient and long-lived profession.

It made me ask grainier questions about traditional knowledge, about its mechanics, about how it helped art shape social cognition. I studied tradition more as paddhati (modality) not just parampara (genealogy), as the workshop that forced artists to connect shastra and samaj.

I wanted to create a space where this conversation could be captured through research and work with artist communities, where practitioners, scholars and others who are invested in Indian performing arts, could share their insights and concerns.

What is the vision and mandate of your organization? Who are the stakeholders and how do you hope to create impact?

The challenge in theorising on Indian art is to bridge the gap between scholarly work and the language of its experience in society. The other big assumption that we need to fix, is the idea that the ‘performance’ in performing arts refers only to stage performances (to the extent that all forms of singing, dancing and story telling are today being brought on to the ubiquitous urban stage).

The primary provocative statement I made before setting up CASP is “Traditional art is not entertainment”. I hoped that this would make people ask, what else is it then. I looked for people who worked in the domain of performing arts who would resonate with this idea. And that is how I met Baithak Foundation’s Mandar Karanjkar and Dakshayani Athalye.

I had been working through my Dakshina Dvaraka Foundation (DDF) on public curation of the philosophical perspective of Ananda Coomaraswamy. He draws a very insightful picture about how Indian society nurtured arts practice as a knowledge system and theorized its processes while allowing for it to be expressed playfully and evocatively in the public sphere. DDF did a series of curated performances over a period of 5 years before covid lock down combining art and craft, history and design, to illustrate the unity of Indian aesthetic thought.

Baithak Foundation was deeply concerned about the loss of experience of traditional art forms in common spaces, especially focussing on the loss of access among children of underprivileged, migrant and rural communities. They run an arts appreciation program which they now manage in over 40 municipal and rural schools in Maharashtra.

We combined the two streams of work in art research and intervention and asked the questions about common social patronage for traditional arts practice in Indian society. CASP was then conceptualised as a kind of an R&D space for organisations that are seriously interested in making effective interventions in the field of Indian arts, going beyond archiving disappearing art forms or organising events.

We want to re-tell the story of Indian Arts traditions as being central to the social cognition of society, as a way of knowing the world. In our idealistic moments we would also dream of seeing local markets for art forms flourish so that Indian artists don’t become a charity case for government schemes and NGOs. We want to work with artists, traditional communities that patronise and use these art forms (across economic and social classes), urban organisations, support groups and policy makers.

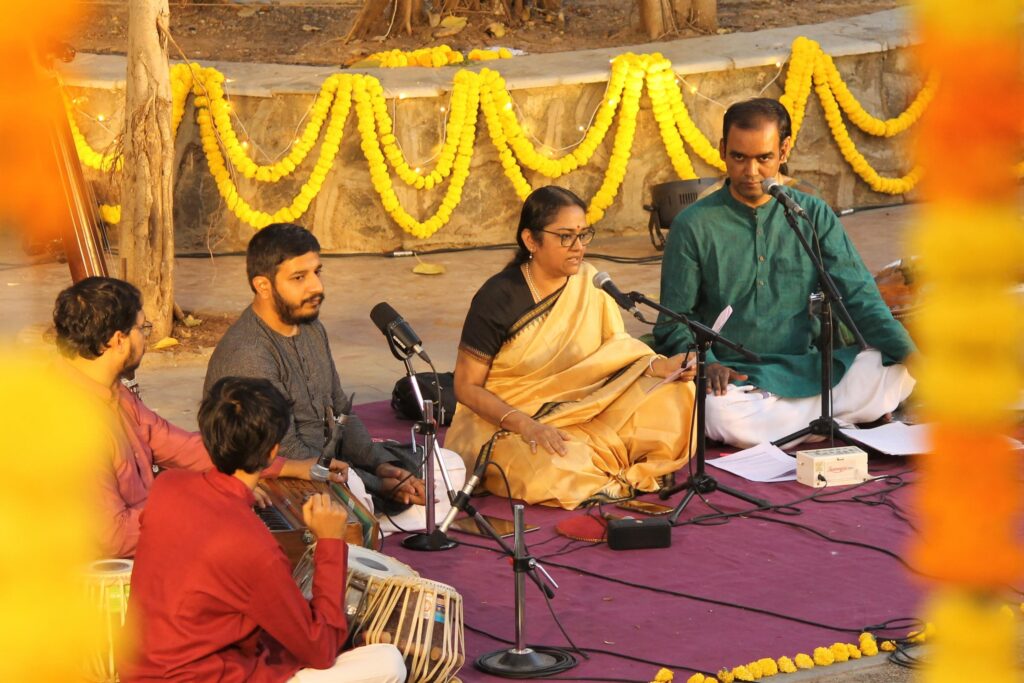

Photo Credit By Sri. S.Harpal Singh, Adilabad

As the daughter of an illustrious Carnatic musician, do you think that such a traditional art form can adapt to changes without impacting its core values? What according to you are the essential values which should be preserved.

There are two things about tradition. How we have come to perceive it and how it actually works. These two often do not coincide, especially in today’s public imagination of what tradition is. Tradition is somehow seen as unchanging and gets defined more through texts than through practice. Anything that is transmitted through aurality changes and the Guru Sishya parampara is more than just an aural mode. As a student of music, I was told to stick to the Guru’s way in more than just musical behaviour. But as a student of History, what I have learnt from watching my mother, her peers and her talented and committed students, is that traditional artists take on a mandate of keeping their art form relevant to contemporaneous contexts.

They have to secure the ground beneath their feet before they speak of values. This ofcourse each artist will do with varying degrees of understanding and conviction to the lineages they represent. The great traditionalists speak of dealing with change not rejecting the idea, slowing it down so that it may be moderated. Two dimensions of music help them, in the case of Raga Sangita, following the oral lineages and the ascriptions to shastra; the other, is social memory of the elements of the form. Both these anchors are referred to by the term ‘tradition’.

In both streams, adapting to change is mostly a technical process. I have watched my mother and several respected elders of Carnatic music speak of the tradition, dilution and realignment with the audience. They were technical discussions. The grammar and syntax of music anchored practice and the social compulsions and tastes pushed ahead the transgressions. This negotiation keeps the art form alive.

That action of negotiation is the core value of tradition.

These negotiations sometimes take place in relationship with an audience community, sometimes in the musicological space and sometimes through technology mediations. As long as there is negotiation there is engagement with the form of the art, from antiquity to now.

In carnatic music for instance, one of the core values is the form and recognition of a raga and this process is, today, vested in the repertoire of the vaggeyakara, their predecessors and their sishya parampara (and those that followed that parampara impressionistically as well). The vaggeyakara compositions are like the early laboratories that combined the best of theoretical frameworks of ancient musical forms, with experiments in compositional form of kriti, that was later adapted to the ubiquitous kutcheri.

Questions of ownership with regards to the arts has so far been addressed along community and caste lines rather than in terms of individual ownership. Is this a shift brought about the economics of performance?

Ownership as authorship, yielding recognition and validation is an old debate. The more recent positions taken by historians and anthropologists largely highlighting inter caste dynamics as being at the core of an idea of ‘appropriation’ of knowledge and the gradual exclusion of some communities that were holders of art knowledge in the previous century from modern performance spaces, address very limited historical questions. I think many historians also are looking beyond these binaries to look at issues of technology mediations, sovereignty of economic practices etc. There certainly is an important conversation there, which society needs to have and resolve, regarding exclusion and appropriation of knowledge.

Appropriation is one way of looking at transgression of a knowledge genealogy. When we ask how musical knowledge passed through the 20th century, much as we may ask how did the knowledge of stock trading pass, we will encounter instances of linear progressions but also transgressions and complete discontinuities of practice. Knowledge will pass on between spaces and communities, as its systems transform. It is not the job of the Historian to judge these processes, merely describe them to the best of their methodological capacity.

Every era of History writing has some predominant social concerns which gain centrality for the Historian. In the past 2- 3 decades or so the foremost concerns of historians and sociologists of Indian society have been related to caste, religion and politics. It is not a surprise hence that these concerns reflect in writings on traditions of art practice.

Mandar Karanjkar, Dakshayani Athalye and Sushruti Santhanam (centre)

Sociological tools to study society are often inadequate in the arts. What new ways can we study Indian art performance and its changing nature today?

The answer to this continues from the previous one. Historians must also address the gaps and inadequacies in the basic theoretical framework within which academic writing happens, whether in history, anthropology or ethnomusicology. For instance, traditional arts practice in India challenges very basic working definitions and binaries like theory and practice, tradition and innovation which are commonly seen used in academic writing. In some sense this confusion has even entered institutionalised music instruction, where curricula are divided into theory papers and practical exams.

New tools and perspectives to study Indian art traditions are going to have to come from studying their techniques, not just those that are contained in texts, but those that are embodied as creative techniques and listening practices, as techniques that translate sound and vision into a collective of cognition of raga and hasta mudra. We have to also look at how these processes are entrenched in the vocabularies of communities that use and patronise art forms.

Indian art forms are very unique not just in content but also in their transmission. They can add value to largely Western models of AI and IPs. Should we evolve new laws which are more relevant to the Indian context?

The reason why I began looking at Intellectual Property Rights, copyrights, patents and GI, that are now being discussed in relation to the practice of traditional arts, relates precisely to your question. For centuries knowledge in the arts has been transmitted through processes of imitation, interpretation and experimentation. Should we not first understand how this was done before we claim to secure it through laws that were created elsewhere to suit the requirements of an entirely different social value system.

Consider this, applying copyright laws to music is a transference of laws from publishing to performing, which are two different modes of knowledge production. Even if we are to consider the music industry and reproduction of music as being aligned to publishing, there are vast differences in how we view authorship when it comes to traditional music/arts. Its modes of ascription, stakeholding, contributions, validations are very different and perhaps have been seminal in shaping the art forms as we see them today. Should we not ask what would happen to the art form if we change the modes of ownership without consultations and deliberations? That is the theme of this year’s edition of Talking with Tradition, our yearly conference.

A Pre-Event Huddle At The CASP- Baithak office

How are you documenting local art forms and how far have you progressed in your work?

Documenting art forms and making databases is one kind of work. The question that we ask is how can such a database benefit the practitioners? There are government schemes that benefit a few artists but the survival of any practice depends on the sustenance given from local markets.

We have just begun a project in Solapur where in collaboration with an eminent industrial house and the Solapur University, we are enabling students to do a survey of musicians, dancers, storytellers and such art practitioners in the district. The involvement of institutions and the community at the district level, would mean that they are invested in the data that is produced there. The visibility of the project we hope would create impetus to revive the market for the artists within the district.

Another project we are starting in the Northeast, helps communities document their own disappearing art and crafts practice.

Video Excerpt of the Interview