By Ian Lockwood

Several years ago my family and I took an eye opening day trip to the Sholai School just down the hill from Kodaikanal. The visit has helped me think about ecological teaching and learning as well as themes that are at the center of my work as an educator, photographer and writer. I entered the teaching profession in order to make a living learning and teaching about the planet with a special focus on South Asia. Increasingly, as I was reminded of on this trip, the idea of sustainability has come to be a central theme in my professional and personal life.

The Sholai School, also known as the Center for Learning Organic Agriculture and Appropriate Technology (CLOAAT), was set up by Brian Jenkins in 1989. It has grown slowly and now has considerable land area and a broad range of educational goals that it addresses. The school size is small-only about 40 students- but it addresses a range of ecological and sustainability themes. Students actively participate in their living, food production and the maintenance of the school.

Brian Jenkins the founder, principal and man behind the Sholai School vision. Seen here collecting rubbish at the school’s landmark footbridge.

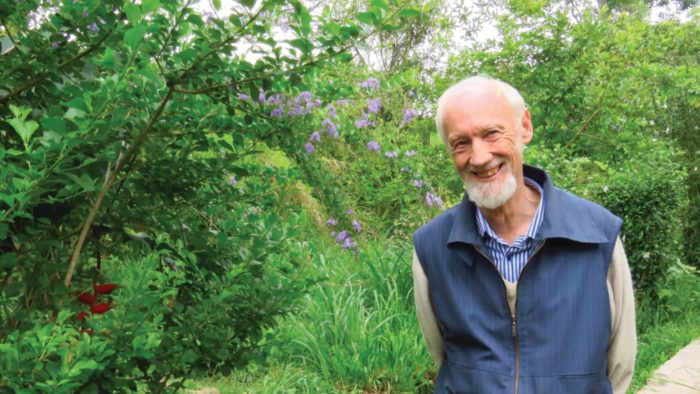

The teaching of J. Krishnamurti have been instrumental in shaping Brian’s world view and the pedagogical focus of the Sholai School. Brian is an old family friend who I first met when he spoke to our senior auto maintenance class at Kodaikanal International School in early 1988. The Sholai School also owns a Stirling Dynamics (India) ST-5 biomass-fueled engine which my father Merrick spent time looking at and advising Brian on.

During the course of our visit we were able to see most of the campus and enjoyed a personal tour from Brian. The school was not in session but the staff was working on various projects and the fields. The Petupari Valley, where the school is located, is known for its coffee, fruit production, home-made cheeses and idiosyncratic people looking to make something different in the world. With an altitude of 1,000-1,400 meters it is a less extreme environment than the upper Palani Hills plateau. This is well suited for agricultural experiments and has the “goldilocks” just-right feel to its weather. Effective water management is a crucial aspect enabling success of the Sholai School experiment. The school uses surface water from streams, collects rain water and also has several wells, such that they are self-sufficient and free of any municipal or government water supply. They are independent of grid electricity and generate power through photovoltaic panels and a micro-hydroelectric turbine. Cooking is done on biogas (fed by waste from cows and the campus toilets) and wood collected from the large compound. The campus includes numerous plots of agricultural land where the community grows much of their own food using organic methods. The buildings, built of stone and covered with tiled roofs, are aesthetically pleasing and look similar to the nearby village hamlets.

We weren’t able to observe classes in session but the critical aspect of the curriculum involves teaching students the practical skills for living sustainably. The Gandhian ashram ideal has influenced the planning and the whole community participates in daily maintenance (seva) of basic needs. Although Brian has had his differences with neighbours there is clearly an attempt to break down barriers and invite the local community to participate in the experiment. I appreciate this, remembering how so many international schools that I have been associated with function as bubbles of elitism in their communities.

At the Sholai School there is an emphasis on hands on learning that primarily focuses on providing healthy, organic food. Brian has a special interest in mechanical learning and there are automotive and wood workshops, reminiscent to me of Johnny Auroville’s place. Brian’s historic 1930s Austin 7, the vehicle that our class had inspected in 1988, is still working and Sholai students get a chance to work on it and several other vehicles. Place-based pedagogies are important and the students learn about the area’s biodiversity, the traditions of the Tamil villages and the history of the area. I was thrilled to see that they have a GIS lab and have done interesting work in map the watershed that their streams are fed by. The school offers students a chance to sit for the Cambridge (IGCE) exams, which allows them a chance to re-enter the other world and attend university. There are also opportunities for older “mature students” (university age) to spend time learning at the Sholai School. Clearly the Sholai School faces its set of challenges: recruiting and retaining faculty and staff is difficult and it takes a special teenager to take on the challenge of living and learning in its isolated valley. Brian is charismatic, headstrong and clearly eccentric, but he is a passionate voice for sustainability in the wilderness.

Further up the hill from Sholai School is Kodaikanal International School (KIS), now moving into its 118th year. It is an established school that played a historic role in introducing the International Baccalaureate into India and the South Asian region. Ideas of critical thinking, service to the community, an appreciation of the idea of India and learning based on values are important elements of the KIS educational philosophy. As students many of us were exposed to ecological and conservation issues through weekend outings and explorations into the Palani Hills. In my experience, our self-awareness and spiritual growth was nurtured not in the church pew or classroom, but by these outside experiences and the interaction with friends of diverse backgrounds all in a unique, south Indian mountain landscape.

The Ganga Campus of KIS, site of the primary and middle schools. The large area gives a sense of the “old kodai”- cool, spacious and green.

KIS has its roots in American Christian missions that used to send their children from across Asia to attend what was then a small residential school in a very sleepy, unknown Indian hill-station. My parents were both amongst those children, travelling from Madhya Pradesh and Ceylon to a far off place called Kodai. All that has changed now and the school caters to a largely urban Indian/global clientele.

The town has grown into a small urban area with year-round tourist traffic (think of Daytona Beach crossed with a picaresque hill station, set to a pulsating Bollywood dance number!). The school is physically surrounded by this growth, though it has some of the largest, green pieces of property in the township. The school maintains excellent academic standards, places students in outstanding world universities and has produced citizens that seek to change the world in a positive way. Service to the local and global communities are important values in KIS but students are nevertheless pampered.

Many of the students come from extremely privileged backgrounds and a large, hard- working support staff helps to keep the campus fed, clean and running. Environmental education is thus far limited to a classroom, service projects and the hiking program and there is room to explore ideas of sustainability. As an educator and KIS graduate it seems that there is much to be learned from the Sholai School experiment just down the ghat road. 21st Century learning, an evolving pedagogical idea of our times, will have to extend itself from using media and technology in learning to addressing the pressing ecological needs of our times. Sustainability and how we as a species can thrive and survive without destroying our life support systems is a fundamental focus need for education. As KIS and other residential schools in India look to empower students with ecological world views and a greater understanding of sustainability, the Sholai School experiment offers a small-scale case study of a possible pathway.

(Ian Lockwood is an educator, photographer, and writer with a life long interest in the ecology, landscapes and cultures of South Asia. He has a special interest in tropical forests, obscure mountain peaks and conservation themes in the Western Ghats/Sri Lanka biodiversity hotspot.)