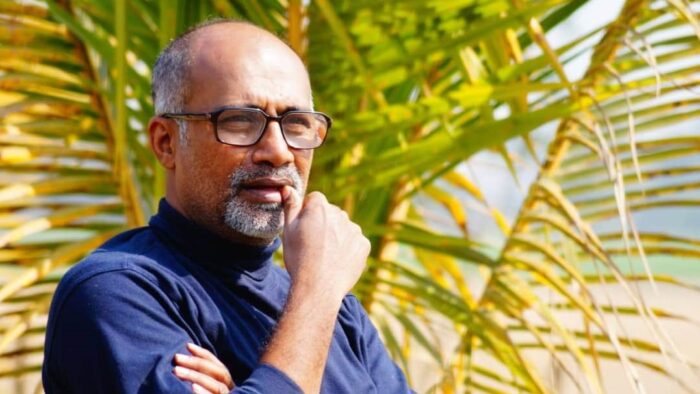

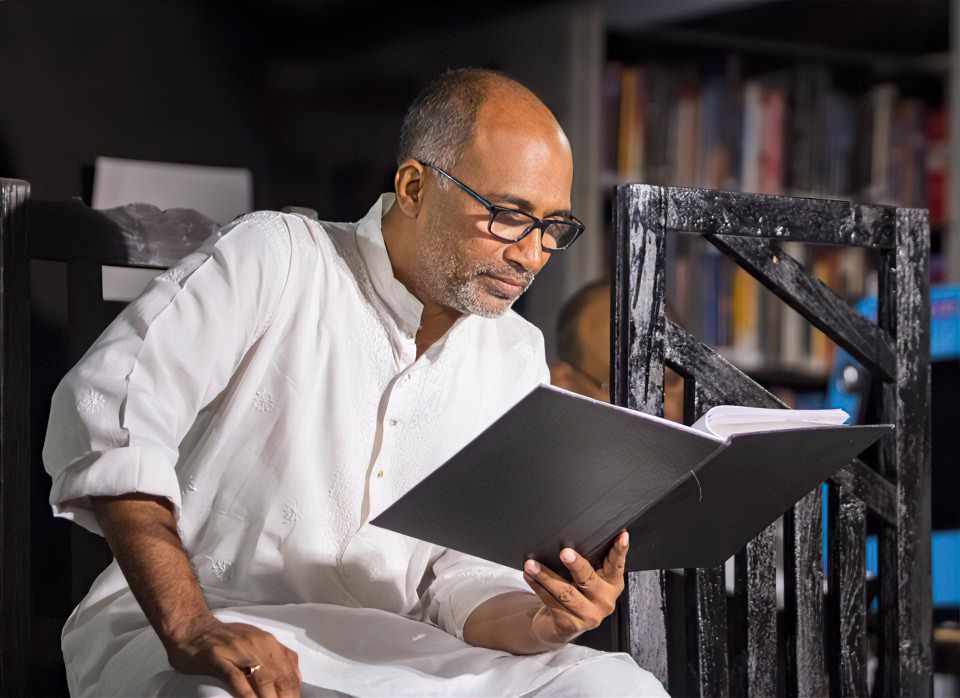

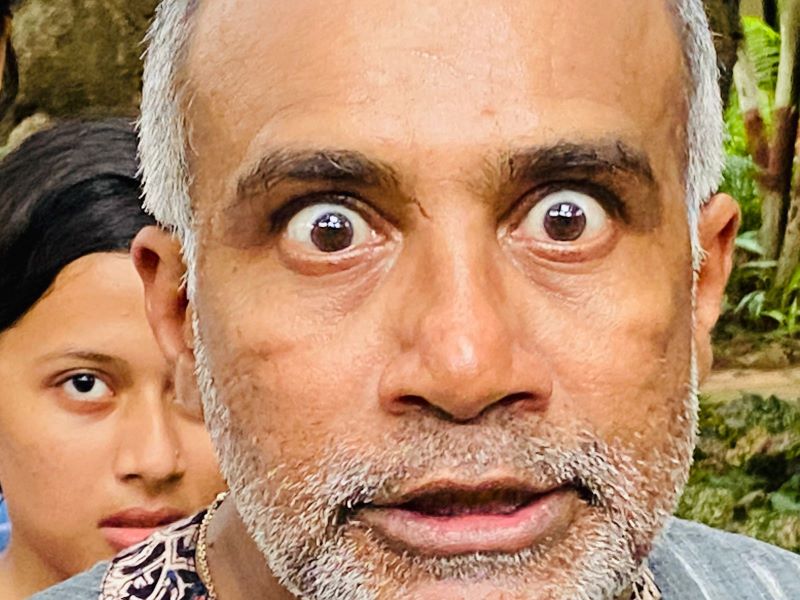

Dr Janardan Ghosh is a performing artist, academic, theatre director, fim actor, playwright, performance coach and storyteller (Katha ‘Koli, a new art of storytelling) whose practice includes the use of traditional theories, contemporary performance vocabulary, and interactive media. His research-based work engages the indigenous practice methods in urban spaces exploring the perspectives of historicity, spiritual consciousness, intertextual dialogue, and body-space dynamics of myths, tales and gossips.

He has trained and worked with several international and national theatre and film directors and is a critically acclaimed contemporary theatre practitioner in Bengal.

He has acted in plays, webseries and award winning movies. He has been awarded for Performance in Education for Social change by Monash University, Australia and The Telegraph. A film where he played one of the leading reading role – Kalkokkho was selected for the competitive section of the Busan Film Festival, 2021.

How did you get interested and get your training in the regional and cultural theatre of West Bengal?

I was born in Dhanbad. My school and my father inspired me to peep into the world of theatre at my birthplace. I got initiated into Bengali theatre when I came to Kolkata for my higher studies. I started with a small group theatre named Taranga (North) and gradually got introduced to the mainstream group theatre movement through the extraordinary actor-director-singer Anjan Dutta, theatre director Jayati Bose and the legendary theatre activist Badal Sirkar. While Mr. Dutta and Ms. Bose trained me in the art of theatre, Badal Babu shaped my philosophical ideas. The popular Bengali theatre was influenced by Western theatre from its genesis. Kolkata theatre is very much Stanislavski, Brecht, Beckett and Grotowski. So, initially, I was groomed into Western techniques and theories and was extremely impressed by Badal Sirkar’s Third Theatre. Onstage, I explored Tagore, Shakespeare, Manoj Mitra, and some original texts written by me and in intimate spaces, we explored Badal Sirkar’s texts and various original texts from Jean Genet to Tantra to Ramayana.

However, gradually, from the elaborate stage performances, I shifted to minimalistic performances in intimate spaces and audiences in the round. I also had the opportunity to have an understanding of Forum theatre under the tutelage of Dr. Sanjay Ganguly and Jana Sanskriti. Thereafter, my academic research (PhD) on Spirituality in Performance ushered me into the world of indigenous performances and classical Indian theatre. I got extremely hooked on folk performances, especially storytelling performances, like Kathakatha, Palakirtan, Patachitra, Gambhira, etc (I interacted with Patachitra artists of Nayagram, Kirtaniyas from Nabadwip and Gambhira artists of Malda) and eventually tried to develop a storytelling performance named Kathabhinaya, adopting elements from my Western training (I got trained by Wulfgung Kolneder, Germany, Włodzimierz Staniewski, Poland and others) and the folk art forms from the practitioners.

Are there many explanations for the origin of Bengali theatre? Which according to you is the more far-reaching influence - Vedic or Folk? What evidence do we have of this?

Many theatre historians claim that Bengali theatre began in the 19th century during British rule in India. However, though it is true that the visibility of the form and technique in the theatre of Bengal increased with the English influence, various indigenous forms of theatres existed and thrived in Bengal for more than a thousand years. Scholars like Selim Al Deen and Manamathamohan Basu state that even the classical Sanskrit theatre had no role to play in shaping Bengali theatre, it was the folk theatre that flourished in ancient Bengal. In Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra, Pravṛtti has been mentioned as “nānādeśabeṣabhāṣācārāvārtāh”. Country-Dress-Language were the determinants of Pravṛtti. There are four Pravṛttis and Odramḡadhī represents the Pravṛtti of Bengal. Bhāratī and Kauśikī Vṛttis form the Odramāgadhī Pravṛtti. To perform Kauśikī Vṛtti, born out of Shiva’s dance, Lord Brahma created twenty-three Apsaras. The form is repleted with various gesticulations, songs and musical compositions (Bahunṭtagītvādya). There is a difference between Nṛtya and Nṛtta. While Nṛtya is the classical dance form, Nṛtta is folk gesticulations performed on the beats of music. The earliest Bengali performances yet discovered are found to be based on Nṛtta and the Kauśikī Vṛitti. Prof. Basu claims that from Nṛtta performance in Bengal evolved to Nṛtya to Nāṭya. I feel Bengali Nātok (Hereafter, I shall not use theatre, but the word Nātok. However, the word Nātok has a debatable origin. While some scholars claimed that Nātok came from Nātaka, a form mentioned in Daśarūpaka in Nāṭyaśāstra, others stated that it came from the word Nāṭya, which included dance and singing.

In ancient Bengal performances were termed as Kāc, Nāṭya, Līlā etc.) emanated from folk rituals related to the worship of Gods and Goddesses, like Shiva (known as Nataraj, Natesh, Natanath, Adinath etc.), Chandi, Manasa, Dharma etc. In Shatapata Brahman, it is mentioned that the fire of the Vedic Yajñas that originated from the banks of river Saraswati was blown off at the banks of river Sadanira (Karotoa river). Beyond the banks of Sadanira was Bengal or Vangadesh. So, the culture and art practice of Bengal grew without the influence of the Vedic culture. The Nātok grew from Shivotsav, Shiva rituals. We still have the residuals of those rituals in the form of Charok and Gajon. Gambhira performance, originating from Shivotsav still exists in greater Bengal. It is a three-day festival of performance, the first day is the beginning of dance and songs, followed by a Mask dance on the second day and on the third day we have dances of the ghosts and fire acrobatics etc. Many commentators have stated that Shiva’s drink named Siddhi in Bengal is similar to the Vedic drink Soma. The great poet Kriitibas in his Bengali Ramayan, mentions the popular episode of Shiva’s wedding in Uttarkanda. This episode is also found in old limericks. Bengali girls still worship Shiva for a husband as powerful as Shiva. Apart from such pieces of evidence, we do not have any substantial written text. The earliest Gītikāvya available is Shunyapuran. Ramai Pandit from the 10th century AD, during the reign of Dharmapal II, wrote it. The Bengali religious practice of that period was influenced by the Śunyavāda of the Buddhist tantra. The Shivotsav had then taken the form of Gambhira and Gajon festival of Dharmathakur. Dharmathakur was worshipped for having children. Shiva was then considered to be the prime devotee of Dharmathakur. This is a very common phenomenon in Bengali religious belief system, they never abandon Shiva. When Vaishnavism was in its prime Shiva became a great Vaishnava and would perform Haribhajan with his five mouths. Shiva is also shown as the mendicant asking for alms from Mother Annapurna, Shakti. It is well known that the Sun God Surya is replaced by Shiva. Shiva is a Dravidian word, meaning the colour of blood (raktavarna): the colour of the rising Sun. Shiva has interestingly changed his status in the Bengali pantheon but never lost his relevance. The shifting dynamics of Shiva were the source of many creative performances along with rituals. The stories of hope and human desire were the central themes of Gītikāvyas, which were popular among the common folks.

Are there tales to support this, like the one you mention about Suryayi and Gowri. Did this kind of conversational song-based dialogue lead to a particular kind of theatre?

Yes, like Suryamangala songs many short and long “performance songs” were there which are lost. From these folk songs grew the Mangalkāvyas. The 17th-century Kāistha poet, Ramkrishnadev wrote the Brihat Shivayan Kāvya, which was influenced by Sanskrit Kāvya and Puran. However, around the 18th century, Rameshwar Bhattacharya, a Hindu Brahman, wrote another Shivayan portraying Shiva as a farmer, showing folk songs' influence. Hence the Gītikāvyas were not only emerging and evolving from indigenous folk songs but also had strong influences of Sanskrit Puranas, Itihās and Kāvyas. Both the above-mentioned sources were equally dramatic. During the Buddhist Tantric period, Dharmathakur rose to greater importance than Shiva and many Dharmamngal Kāvya were constructed. Apart from those Kāvyas, many other Kāvyas and Kāhinīs were written on the lives of Gorokkhanatha and his wise and powerful disciples. Among those Gītikāvyas the stories of Bengal’s King Manikchandra, his queen Maynamoti, and their sons Govindachandra and Gopichandra became the most popular and well travelled performative songs. It is assumed that Manikchandra ruled Bengal in the late 11th century. Queen Maynamoti was the disciple of Mahāyogi Gorakkhanath. By His grace, Maynamoti was empowered with potent magical powers; one call, “Tuṛu tuṛu koriā hunkār”, and the thirty-three crores of Devatās along with Ramlakshman, Panchapandavas, and Munirishis would drop down from heaven. Even Yama was scared of her. Shiva as usual features in this tale as the guardian of the farmers. When Manikchand started exploiting and torturing the farmers —

“Āchila ḍeṛ buṛi khājnā loilo ponār ganḍā.

Lāngal becāy jongol becāy āro becāy fāl.

Khājnā tāpete becāy dudher chāoāl.”

— they came to Shiva for help. Shiva consoled them and told them not to worry as Manikchandra was fated to die after six more months. However, He warned them to keep it a secret and Maināmoti should not know or else she would destroy his Kailasha, “Kailāś Bhuvan mor koirbe lanḍa bhanḑa.” This narrative song was full of drama and action, this story gained popularity because human beings were shown as more powerful than the Gods and they could obtain this power through Sādhana. In these Gītikāvyas, the performative aspect and the dramatic elements were in abundance. Among the ancient theatre scripts discovered in Nepal, Gopīchandra Nātok is a prominent one. The Mangalkāvyas of the Middle Ages had dramatic episodes and characters like Chandsadagar, Behula, Kalketu, Khullona, Shrimanta, and Bhanṛu Datta. Elements were profusely drawn from Ramayan, Mahabharata, Shrimadbhagavat and other Puranas.

Pieces of evidence of Śrī Kṛṣṇakīrtan are found in the middle ages, which are interspersed with dialogues between Kṛṣṇa, and Baṛāi. The padas are examples of Aṇu-nāṭya. Baṛucanḍīdās was a specialist in creating such dialogues. Canḍīdās was also a puppeteer.

You are trained in indigenous practice methods exploring the perspectives of historicity, spiritual consciousness, intertextual dialogue, and body-space dynamics of myths, tales, etc. Did any of Indian traditional performative elements influence Western theatre?

Rasa theory has impacted a lot on Western performers and theatre practitioners. From Richard Schechner to Philip Zarilli to Peter Brook all tried their best to comprehend and use the theory of Rasa in their performance idioms. Chapter six of The Nāṭyaśāstra provides a thorough listing and description of the eight rasas, which include, Vīra (courage), Bhibhatsa (disgust), Bhayānaka (fear), Sringara (erotic, love), Hāsya (humour), Raudra (rage), Karuṇa (compassion, pity), and adbhuta (wonder, awe) and Abhinavagupta added the ninth rasa Śānta (peace). “Rasa iti koh padārthā. ucyate āsvādyatwāt”. According to Dr. Nagendra, the word Rasa in the sense of aesthetic delight came to be used probably during the fifth century B.C. to the second century, B. C. Abhinavagupta stated that the purpose of performance is bliss or pure pleasure: “Rasa consists of pleasure, and rasa alone is drama, and drama alone is the Veda” (Masson and Patwardhan). According to Abhinavagupta, rasa is not merely a psychological experience but a transcendental one, which involves “the return of consciousness to its own innate and universal but immediate ecstatic nature” (Gnoli). Schechner devised a system to explore Rasa named Rasa Boxes around 1980-90s. It was designed to allow performers to explore and use their feelings and emotions in various performances. It claims to integrate ancient Indian theory with contemporary emotion research: termed as Brain in the Belly, facial expressions, neuroscience and performance theory. It is very much Visceral. Rasaboxes exercises are considered to engage the whole mind and body, it is psychophysical. However, I find the exercise and the Rasabox concept a little constricted.

Rasa is a complete experience, not fragmented between performer and audience. Rasa is an indescribable phenomenon, binding it to a structured formula narrows the scope of comprehending the vastness and subtlety of the happening. Schechner’s Rasaesthetics provide a comprehensive and simplistic understanding of the Rasa theory but not the essential experience. Rasa happens. The conception of rasa is based on experience. Bharata has established the colour and the presiding deities of the different rasas as they were handed down by tradition. He has provided the vibhāvas, anubhāvas and vyabhicāribhāvas for all eight sentiments. Bharata also introduces abhinaya (acting and more, which I will discuss later) for expressing the anubhāvas. The vibhāvas, according to Bharata, are to be dealt with by the poet, and are to be expressed by creating an ambience either through verbal renditions or other means. The anubhāvas are to be expressed through gestures, which would eventually lead the spectator to deduce the sentiment or rasa. Thus the actors in a performance, which has an appropriate ambience and characters (vibhavas), use appropriate gestures expressing the mental states (anubhāvas) and the transitory moods (vyabhicāribhāvas) to produce the rasa within the spectator as depicted by the poet.

The vibhāvas or determinants are the conditions and objects which give rise to the emotions. For example, in Rāmāyaṇa, the determinants of the emotions within the Rāmlīlā performance are Daśaratha’s hasty decision to give two boons to Kaikeyī, Mantharā’s advice to Kaikeyī, Sūrpaṇakhā’s sudden visit to the forest and an unexpected meeting with Lakṣmaṇa. These factors dramatically generate the story of the performance.

The anubhāvas include the performer’s gestures and other means of expressing emotional states. These may be involuntary such as sweating, shivering and trembling or voluntary such as deliberate actions and gestures. For example: Hanumān’s unexpected bodily growth, Rāvaṇa’s anger during Rāma’s exile.

The vyabhicāribhāvas are the ‘Complementary Psychological States’ which exist temporarily in a performance, but contribute to the overall emotional tone of the play. In Rāmāyaṇa, Sugrīva’s initial doubt about Rāma, Rāma’s army not believing Vibhīṣaṇa’s change of sides, Bharata’s angry outburst at his mother, sarcastic attitude towards the king Daśaratha, Rāma’s helplessness and despair at the loss of Sītā, are some of the fleeting emotions which contribute to the major theme of the play.

The inner idea of the poet is made to permeate the mind of the spectator by means of chanting words, gesticulation, facial colour, and the representation of the temperament. The mental states are the cause of the manifestation of the sentiments (rasa) in the performance.

These mental states are known as bhāvas.There are forty-nine bhāvas (8 sthāyibhāvas, 33 vyabhicāribhāvas, and 8 sāttvikabhāvas), which are capable of exploring the vast range of human behaviours.

Sāttvikabhāvas are the temperaments which are achieved through concentration of mind. The bhāvas originate in the mind. The sāttvikabhavas are as follows—Stambha (paralysis), Sveda (perspiration), Romāñca (horripilation), Svara-bheda (change of voice), Vepathu (trembling), Vaivarṇya (change of colour), Aśru (weeping) and Pralaya (fainting). The temperament is required to represent experiences since they are the imitation of human nature. These are artificial representations created by the actor by imagining the situation and acting it out. The effect of the powerful mood is not reflected in the physical body of the actor until and unless the actor is one with a particular mood. The actor may not suffer a sad mood but has to show the suffering of the character if needed through his physical appearance. This requires special mental training which will affect the physicality of the actor as per the required mood. This special effect of the mental state is known as sattva. This entire gamut of physical acting, mental state and more, is known as abhinaya in Nāṭya Śāstra.The sentiment of the play is conveyed to the spectator through Abhinaya. According to Bharata, abhinaya is of four kinds: Sāttvika (temperamental), Āṅgika (physical), Vācika (verbal) and Āhārya (dress, makeup, etc.).

Bharata’s own summary of his dramatic theory is as follows: “The combination called nāṭya is a mixture of rasas, bhāvas, abhinayas, dharmīs, vṛttis, pravṛttis, siddhi, svaras, instruments, song and theatre-house”.

While Western practitioners usually tend to structure everything for its utilisation, Art practitioners in the East cross the threshold of the comprehensible constructed level to a state of esoteric obscurity beyond the well-structured and rehearsed material. I believe that a big leap leads to the experience. A leap is indispensable.

I found Eugenio Barba deeper in his search and use of Indigenous methods or techniques. One of his passages on Indian Art practices endorses my views. He writes, “Continuity in the arts relies on human beings. Written texts may record certain principles, but the belief in the efficacy of the living teacher goes back to the time of the ancient sage/teacher, Narada: ‘What is learnt from reliance on books and is not learnt from a teacher does not shine in an assembly’.” Most of the crucial knowledge is transferred through non-verbal means and their nuances of expression exist beyond words.

What is the Sanskrit influence on Bengali theatre and is it restricted to a particular region?

Many Nāṭyaśalās built by the Hindu Kings were destroyed with the advent of the Muslim conquerors. A few pieces of evidence of the performance spaces constructed by the last Hindu ruler Lakshman Sen are found. During his reign, the poet Jayadeva wrote Gītgovinda in Sanskrit, however, it has elements of folk performances. Dr Ajit Kumar Ghosh argues that though the Gītgovinda was written in Sanskrit the form and performative element present in it is that of a Gītināṭya. We know that William Jones had defined this work as a pastoral drama. A similar trend is observed in Caryā Padas. On the other hand, the folk performances were found to adopt elements from Sanskrit Drama. Lord Caitanya’s performances described by Vrindavan Das in Caitanyabhāgavad are important examples of such an amalgamation of the classic and the folk culture in Bengal. Caiatanya’s disciple Rupa Goswamin wrote plays in Sanskrit, like Bidagdha Madhava, Lalita Madhava and others. He strictly followed the norms of Sanskrit Drama in his plays. He constructed a Bhāṇikā named Dankeli Koumudi. Swarup Damodar and Rai Ramananda were the other two disciples who accompanied Caitanya in his theatrical ventures. Rai Ramananda was an experienced and expert theatre director. He directed the play Jagannath Ballava. Sanskrit theatre thrived in Bengal during the Vaiṣṇava period.

After the introduction of Western English plays in Bengal, people desired to have something similar in their own language. However, there were no Bengali plays as such, so, Sanskrit plays were translated in Bengali. A six-act Rupaka play named Prabodhchandrodaya was translated into Bengali as Atmatatwakaumudi in the year 1822. The same year, another Prahasan was translated from Sanskrit Hasyarnab, it is assumed that it might be a translation of Jagadishwara’s Hasyarnab. In the year 1828, Ramchandra Tarkalankar translated another Prahasan named Koutuksarvasya. Twenty years later, Ramtarak Bhattacharya translated Abhigyana Shakuntalam and Nilmoni Pal translated Shri Harsha’s Ratnabali in the year 1849. Two original plays were written in the year 1852, Bhadrarjun and Kirtivilas and had elements of Sanskrit plays along with Shakespearean influences. They were five-act plays, but Kirtivilas began with Nandi and then Sutradhar took over.

The translation and performance of Abhigyana Shakuntalam by Nandakumar Rai in the year 1855 was a historical moment, as it is considered to be the beginning of Bengali theatre. Later Bengali playwrights like Ramnarayan Tarkaratna and Michael Madhushudan Datta were strongly influenced by Sanskrit plays. Ramnarayan’s first play Kulinkulasarvasya can be classified as a Sanskrit Rupaka play and he wrote three Prahasanas. Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar translated Bhavabhuti’s Uttarramcharit and Abhigyan Shakuntalam. Kaliprasanna Singha translated Vikramorvashi and Malati Madhava. Dinabandhu Mitra, Jyotirindranath Tagore, Girishchandra Ghosh and Dwijendralal Roy translated many other Sanskrit Plays.

What is the connection between Performance and Spirituality in Bengali theatre? Is this to be found in any other genre of theatre around the world?

We have already seen that Bengali theatre is born out of religious rituals. However, the experience of the performer and the audience can be investigated to locate its Spiritual facet. The religious rituals like Shivotsav had a spiritual goal for the practitioners, which percolated into the performance idiom. Shiva’s romance, meditation, anger, affection, farming, weaving, acrobatics, music, theatre and dance all were the ingredients of early Bengali theatre. In the contemporary Gajon festival, we find remnants of those rituals. The participants reach a state of trance, walk on sharp blades and jump on fire beds. Gambhira performance includes the mask dance; wherein the performers use masks of Kalika, Chamunda, Shiva, Ram Lakshman, Hanuman and others. The folk origin of Bengali theatre carries the spiritual virtue in its later contemporary forms. Later, we have more structured performances like Dharma Mangal and Gītgovinda. Dr Manamathamohan Ghosh mentions that the ‘Bhagavatprem’ has entered the system of the Bengali race to such an extent that it cannot be destroyed without rubbing out the entire race itself. He gives an example of a family play ‘Lilavati’, where she sings a song

“Who says my Kānāi is not in Gokul

I get his fragrance at all times

His ankles tinkle in my heart

It makes the ‘runu jhunu’ sound, you all please listen…”

From Dinabandhu Mitra to Maharaj Durgacharan Laha all started weeping profusely. The spiritual bhāvā was predominant in early Bengali theatre. Then there was an abundance of religious and Puranic plays to provoke spiritual emotions in the audience. However, many considered them to be of no greater quality and essentially melodramatic. These scholars avoided noticing that the Indian ethos is essentially spiritual. As the legendary theatre critic commented about passion Plays: “The moving force behind it— the thing which kept the audience silent and spellbound on hard seats for eight hours, unmindful of cramped limbs and aching bones—was the force of tradition rather than dramatic virtuosity, of emotion rather than judgement, of religious awe rather than artistic appreciation.”

There was a rise in the popularity of Puranic plays during the life and times of Girish Chandra

Ghosh in the early part of the 19th century. His plays like Ravan Badh, Sitar Banobas, Lakkhan Barjan, Ramer Banobas and others evolved out of Krittivasa’s Ramayan and explored Dharmabhāva and Devamahātmya. He also wrote, directed and enacted plays based on Mahabharata and other Puranic tales like Abhimanyu Badh, Pandav Gourav, Dhruva Charitra, Kamale Kamini, Nal-Damayanti and many others. His two plays Chaitanyalila and Bilvamangal were deeply rooted in spiritual understandings. Sri Ramakrishna went to see these plays. Thereafter, he became Sri Ramakrishna’s devotee and was significantly influenced by Sri Ramakrishna’s philosophy, teachings and style of conversation. Many of the plays he wrote after Caitanyalila (1884) show traces of Sri Ramakrishna’s influence. Performers like Binodini Dasi, Vidya Sundar and others were praised and blessed by Sri Ramakrishna for their extraordinary performances. Sri Ramakrishna assured the performers that they would be able to reach God through their performances. Gradually there was a decline in plays containing spiritual essence and Bengali theatre was flooded with political and social plays.

Later in the 20th century, we find a brief revival of Bengali Puranic plays with playwrights Manmatha Rai (Karagar, Devasur, Savitri, Chandsadagar), Jogeshchandra Choudhuri (Sita), Mahendra Gupta and others. In the 21st century, we rarely have plays reflecting spiritual comprehension. However, we have tried to explore the spiritual nuances through our performances like The Otherness of Being based on Raganuga Bhakti Sādhana, Digambarim exploring the power of Śakti Sādhana, Paramahamsa based on life and teachings of Sri Ramakrishna and the present production based on a folk retelling of Ramayana, Ramayan: Fractured, Fixed and Foretold.

I feel the dividing line between art and spirituality is so narrow and so easily crossed. Goethe says, “ Art rests upon a kind of religious sense; it is deeply and ineradicably in earnest.” For me going to the performance space is similar to going to the temple.

In your interactions with foreign theatre groups, do you see an interest in these religious/spiritual theatre themes?

When we talk about the sacred drama, what do we mean in particular? To a layman, sacred drama includes plays based on religious themes and hagiographic tales of saints and all performances with religious implications. However, I believe all performances irrespective of themes and tales must generate spiritual resonances to be considered sacred drama. Hence, we can enlist a host of theatre practitioners and experts who have contributed to the shaping and enriching of the sacred drama.

Ralph Yarrow is known for his seminal book called Sacred Theatre. I met him in person and had a long discussion on his book when he was in India and have borrowed ideas and information from his collection of essays to frame my concept of sacred drama from the West. He writes, “Theatre has the ability always to come up with something unexpected, and it is important to explore precisely the forms and scope of that unexpectedness. They may be both profound and perverse: after all, those who have speculated about the nature of the sacred in theatre range from Abhinavagupta to Zeami, from Jean Cocteau to Peter Brook, from Antonin Artaud to Shakespeare (not forgetting Maurice Maeterlinck, Aleister Crowley, Rabindranath Tagore, Kavalam Pannikar and Nicolas Nunes)”. Peter Malekin, while writing about sacred drama and early Greek ritual forms, made it clear that the sacred does not “exist...in subject matter...but in a mode of being”.

Yarrow also said that many practitioners claim that the heart chakra is activated by Noh drama, or by ancient Egyptian and Indian statues, and that at times, all the chakras are fired by the chanting of the Ṛg Veda. Grotowski himself practised the sacred art of unlocking impulses to stimulate organic responses during performances and training. Jennifer Kumiega writes: What the Laboratory Theatre team were seeking in these particular exercises, then, was the possibility of an organic response, rooted in the body, and realized in accomplishment through precise details. Grotowski in fact went so far as to locate the organic source point of the creative impulse –- in the area of the body called in Polish ‘cross’. This, which Grotowski called ‘the organic base of bodily reaction’, is located at the base of the vertebral column including the lower pelvic area of the abdomen. There is a connection here worth noting, with kundalini yoga: according to this tradition, there is a concentration of life energy, represented as a serpent coiled three and a half times, which is dormant at the base of the spine.

Grotowski’s search for the “cross” and Brook’s exploration of the Holy theatre indicates the strong presence of the sacred in drama. Grotowski, in his influential book, The Poor Theatre, claims that when theatre was still a part of religion, “it liberated the spiritual energy of the congregation or tribe by incorporating myth and profaning or rather transcending it”. Grotowski sincerely believed that one can reach the inner core of the self through performance, and he believed in the spiritual energy of performance. Yarrow states that the individual performer of a sacred drama and the spectator feel “complete” in the sense of being in command of and able to call upon an extended range of thought and action.

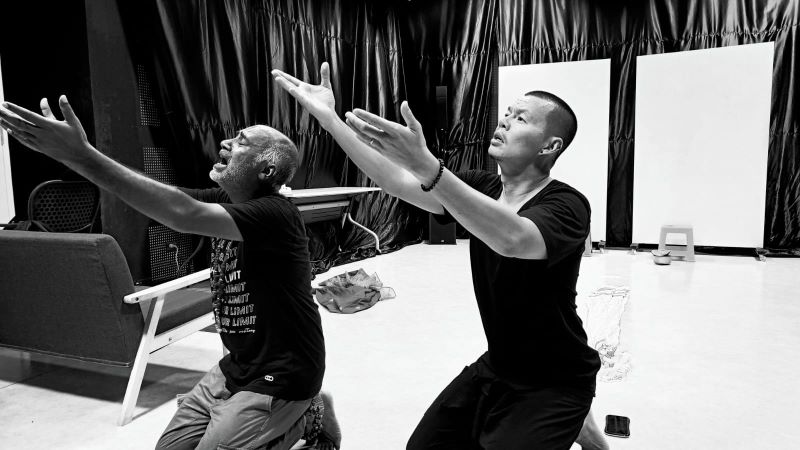

I worked with the legendary Polish director Włodzimierz Staniewski who was with Grotowski from the beginning of his theatre journey. We did Ibsen’s Master Builder together. I had felt his earnest search for a spiritual experience through his performances. When I went to Gardzienice Centre for Theatre Practices, in Poland, I saw their performances and realised their work to be ritualistic and extremely transcendental. The performers would elevate to a different realm.

Sati Gio is a Korean Butoh Dancer. We did a performance named Kali’s Child and Sick Dancing Princess together. Interacting and working with her, I felt that she had this desire to connect with the unknown through performance. Zeami said there are many eyes of a performer. I could see that in Gio’s body. Butoh dancer looks deep inside to create a movement.

How can Rasa theory be used to understand the universal emotions of Spirituality and Art? Abhinavagupta gives a spiritual interpretation to rasa theory, saying the ability to appreciate the universal essences of emotions depends on the audience member’s transcendence of one's ego. Rasa can be attained only by the person who is detached from personal motives and interests and identifies with the supreme universal.

Abhinavagupta interpreted rasa philosophically, claiming that it is samvid-viśrānti (equanimity and composure) or camatkāra (extraordinary phenomenon), which underscored the essential need for specific roles and motives of different artistic media and techniques of within the arts. While Abhinavagupta evolved rasa into a universally recognized aesthetic quality, it was Bhaṭṭanāyaka, Abhinavagupta’s teacher, who had initially brought out the universal character of this subjective experience/feeling. Bhaṭṭanāyaka claimed that drama had a special power. Bhaṭṭanāyaka was the first scholar to explore aesthetic experience in terms of the audience’s inward experience. He argued that the aesthetic experience of a spectator is similar to the experience of having an absolute realization (āsvāda of Brahman) (Gnoli 48).

Mason and Patwardhan remark: “It may well be that Bhaṭṭanāyaka was the first person to make the famous comparison of yogic ecstasy and aesthetic experience”. Abhinavagupta was deeply influenced by these claims of his guru Bhaṭṭanāyaka and he philosophically established rasa as the very soul of drama. For Abhinavagupta, rasa takes a prime position in exploring art and artists and he interprets these experiences as religious experiences. He insists that rasa transcends time and space for both the spectator and the actor and it also goes beyond the limited world of desires and the ego-bound life. Enjoyment of rasa is blissful, and this aesthetic bliss is akin to the spiritual bliss of realizing one’s own identity with the absolute Brahman. Abhinavagupta maintained that the aesthetic experience (rasa) consists of tasting (āsvāda) devoid of any obstacles (vighnas): it is an undisturbed relish. Mason and Patwardhan comment that all of Abhinavagupta’s efforts focus on one important need: i.e. to crack the hard shell of the empirical ‘I’ and allow the higher self to automatically identify with everyone and everything around. So, in the study of Indian aesthetics, Abhinavagupta added a new dimension of spirituality.

An aesthetic experience, according to Abhinavagupta, passes through certain levels, firstly the spectator is introduced to the artistic work, which evokes in the receiver a state of wakefulness. The spectator accepts the imaginary world of performance to be true. Then the spectator is excited, and consequently the emotional situation described in the performance creates “sparks” in the spectator’s consciousness, leading to the revival of traces of his own experiences. The impressions that are enlivened this way come from a whole repertoire of experiences and not just from one particular concrete experience. At the same time, these impressions do not produce any attachment towards the artistic work. Thus, the emotional response is a positive reorientation in the receiver and gradually the receiver abandons the thoughts and concerns of daily life and gets immersed in the act of performance through rasa. The experience purifies the thoughts, will and emotions of the receiver or spectator. Secondly, the full dedication and involvement in perceiving the emotional signals received from the performance create an immersive feeling for the spectator, an out-of-the-world experience (alaukika).

Could you tell us how Sri Chaitanya Prabhu influenced Bengali theatre and how theatre influenced the Bhakti movement?

The stories of Kṛṣṇa were spread extensively through theatre and performances by the Vaiṣṇavas in an extraordinary way. The essential element of Vaiṣṇava philosophy is ‘Kṛṣṇa Bhakti’. Bhakti or devotion was fostered by dancing, singing and playing of music by the Vaiṣṇavas; Sri Caitanya improvised the form of Kīrtan to Nagarkīrtan, which included congregation, procession, music, dance, ecstasy and devotion. Caitanya’s Gauḍiya Vaiṣṇavism also offered the conjoint involvement of the ‘Dhārmic’ practice and Theatre in the same holy space. Caitanya used to arrange for various theatrical performances on different ‘tithis’ and would act different characters himself. He understood the power of theatre and used it best to reach the common people.

During his stay in Nadia, Caitanya directed and acted in many plays, which later enriched and revived the folk form ‘Jātrā’ in Bengal. Śrī Caitanya’s theatrical performances were inspired by the poetic works of Canḍīdās, Jayadeva, Vidyāpati and other early poets of Eastern India. Kṛṣṇadās Kavirāj writes, “Canḍīdās Vidyāpati Rāyer Nāṭakgīti / Karṇāmṛta Śrīgītagovinda / Svarūp Rāmānanda Sane Mahāprabhu Rātri Dine / Gāy Śune Parama Ānanda” (Śrī Śrī Caitanyacaritāmṛta). The Gosvamins and other contemporary followers of Caitanya were equally adept and accomplished in the field of theatre. Śrī Caitanya encouraged his followers and associates to explore the art of performance and write and perform plays and use theatre as a medium to develop and promote Vaiṣṇavism. Life and works of Nityānanda Prabhu, Rūpa Gosvāmin, Rāi Rāmananda, Kavi Karnapura and many others reiterate the claim. The unique Rāganūraga Bhakti Sādhana of Gauḍiya Vaiṣṇavism is based on rasa theory.

Prof. Darshan Choudhury states a few significant points on the style and form of Caitanya’s theatre performance, which I feel might have influenced later Bengali theatre. He states that Caitanya performed ‘Rukmini Haran’ and ‘Vrajalīlā’ in Nadia and performed ‘Vrajalīlā’ and ‘Rāvanbadh’ in Neelachal, Orissa. He enlists the following features:

- The performance used to happen in an open space

- The play was not written or well-rehearsed, only the theme of the play was fixed

- The songs were well prepared and rehearsed

- Dialogues were instantly improvised to complement the theme and include dance.

- The male actors played all the roles.

- The older characters created humour and played comic roles.

- Make-up and costume were important.

- There was entry and exit in the performance.

- Religious feelings and devotion were the raison d’ ětre of the performance

There is a strong debate on the form and style of Caitanya’s performance. While Jātrā is a common feature of his performance, scholars propose three different possibilities from the statement of Caitanya: ‘Āji Nṛtya karibāñ ANKAer bidhāne’ [We shall perform according to the rules of ‘anka’]: a. ‘Anka’ as the Assamese Ankīyā Nat, b. ‘Anka’ being one of the ten Rūpakas from Nāṭyaśāstra and c. ‘Anka’ is used as a term for scene division. While Dr Sukumar Sen claims it to be as per the style of Assamese Ankīyā Nat and the form of Sanskrit play, Bhāna, Hossain asserts the claim to be flawed. Hossain points out the difference in a particular word used by Sen in Caitanya’s statement; Sen uses the word ‘Bandhane’, which means bound by rules, whereas Satyendranath Basu uses the word ‘Bidhane’ as per rules. Moreover, the description provided by Virindāvandās gives emphasis on the emotional [Bhakti Bhāva] content of the performance than the technical aspect of the Play. So, Hossain is unable to decipher the style and form and suggests an influence of the Sanskrit play on Caitanya’s performance and an amalgamation of various folk forms of performances with Jātrā. Śankardeva’s Ankīyā Nat is also considered to be a form of Jātrā. The above arguments prompt us to assume that Caitanya’s performance cannot be pocketed in a single form or style, it was extremely dynamic and experimental. The Bengali theatre which had such a dynamic starting point like Caitanya’s performance rarely took the legacy forward and got potentially diluted by the influence of European theatre. However, one can notice the richness that Caitanya provided through his extraordinary form of performance that evolved out of traditional Jātrā.

Caitanya’s performance can be termed Performance Art in modern-day parlance.

What is the role of theatre according to you, is it to elevate the consciousness of the sadhaka to the level of the divine, or is it to be disconnected from any over-expression of religiosity and restrict itself to the aesthetic of performance?

Yes, for me role of theatre is to help an individual evolve, and elevate her or him to a higher realm of understanding the Self. I believe that it raises the consciousness of the performer (sādhaka) to the level of the divine. When an actor or an audience comes out of a performance he or she is purer than before. Performance can lead you to Mokṡa. Sri Ramakrishna is my greatest inspiration and point of anchorage.

Performance played a very important role in Sri Ramakrishna’s life, beginning as far back as his childhood days when he enacted roles and often surprised the villagers with his performances, which will be discussed later in this chapter. The common womenfolk of the village were unable to recognize him when he dressed as a woman and slipped into their homes. While playing the roles of different gods and goddesses, he would go into samādhi at times, as well as when he saw someone performing such roles. In fact, many of his performances culminated in spiritual realization. I will provide the details later in the chapter. Later, during his period of sādhana, Sri Ramakrishna practised a special kind of vaiṣṇava bhakti incorporating elements of theatrical performances, which I have discussed in earlier chapters. Sri Ramakrishna also was well-known for his storytelling; however, the inherent theatrical skills in his storytelling have rarely been explored. His narrative style and painting of characters while telling a story were unparalleled; the audience was undeniably affected by the stories and some people were even brought to a state of spiritual realization. He also used to sing bhajans, which mesmerized the devotees. And while singing quite often he would go into samādhi (KMG 100,126). Sri Ramakrishna’s storytelling, histrionics and performances as his other creative expressions and involvement were more than a mere artistic creation; they had the power to awaken one’s dormant spiritual consciousness.