I think it is amazing that these people (Bauls) have managed to find a safe space where they can interact and exchange ideas and have shared experiences. It has been going on for hundreds and hundreds of years, and the fact that this landscape is in clear danger of being destroyed is upsetting. My aim is to see how we can protect that landscape, where people from different cultures, with different visions or different voices, can have safe conversation without hitting each other over the head with a stick. The differences that separate us are what makes us interesting. I believe in that freedom, and I feel that freedom has been in danger for a long time - London based Bangladeshi Enamul Hoque

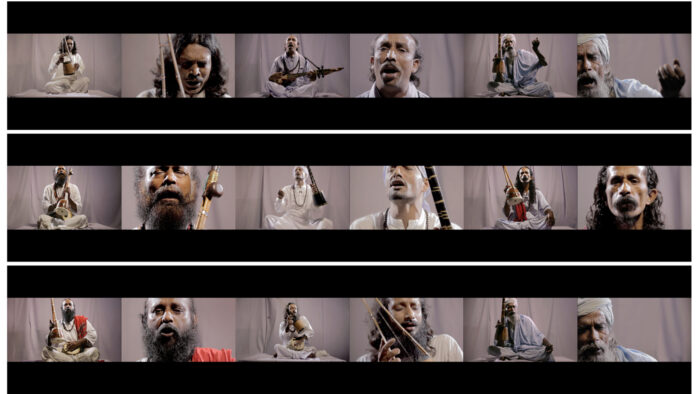

“What is it of the Baul tradition that may lead us towards study? Why should the world take notice of a cult activity almost exclusive to Bengal, practiced by only a minute fraction of a population?” Enamul Hoque asks in his digitised work - Portrait of Baul.

Enamul has played a leading role in ensuring that the traditions and philosophies of Baul, so eloquently expressed in their music, do not fade away. He has spent over two decades exploring and archiving Baul songs and performances in a collection of audio, video and photographic recordings. To date he has collected over 350 songs performed by Bauls. See video: Portrait of Baul by Enamul Hoque on Vimeo

London-based Bangladeshi artist Enamul avers he is not an expert on Baul music. To him, it is ‘a personal story. "It is really a love letter to my family and my mother. Collecting the songs was a tool to talk to my mother. This was a tradition that belonged to her childhood."

It is March 2021 and into the second year of Covid; many of us are far from our loved ones, unable to make trips back home. Meanwhile, India and Bangladesh are mending political fences in a realm far removed from the Baul music that Enamul loves.

A world-renowned photographer, he has been travelling to Bangladesh every year since he was 10 years old. He says he’s a bit distant from his own Bangla community as he came to the UK when he was very young, the first of his family to have an upbringing in the West. “There grew a distance between me and how I communicated with my family. We went through a period where I couldn't explain myself in a manner that they understood.”

When he first started the Baul project, Enamul felt it was something that would help him deal with some of his own inner issues. “It was helping me as an artist and as a creative in the UK, because I’ve never done a project based around my own Bangla identity. When I was going to school in the ’80s there was a lot of racism. We weren't exactly made to feel welcome. So you have this little seed inside your head that yes, you're British but you're not British or you're British but you're not English. Ultimately, if you don't belong you have lots of issues. You feel like your voice is not being heard.”

It was the sound - of the drums specifically - which initially appealed to him more than the lyrics, which he studied later. “In my way of processing information, whether it's creating music, books, films, I'm stuck in between two separate cultures - one being an Englishman, another being a Bengali. The funny thing is I don't feel I belong in either of them. I experience the best of everything, but at the end of the day I don't really feel like I belong anywhere. I feel like a tourist within the Bangla community. When I go home they treat me like an Englishman and when I'm here, they treat me like a Bengali.” he muses ruefully.

Enamul brought his work as a commercial photographer (he has been taking pictures from the age of 10) to the Baul project - the same high standards and professional specifications used in his work with popular household brands in the UK such as Nike and British Airways. The aesthetic he learned in the West rather than south Asia, but this helped in projecting this ancient music on to screens larger than life.

Recordings were done in the natural landscape of the Bauls, but Enamul says he’s a fussy professional and often asked for retakes. “I sometimes got them to do two or three takes before the sound was perfect in a particular song, and the Bauls kept asking me why, why?”

The Call of Baul

Fakir Lalon Shah, was a Bengali Baul saint, mystic, songwriter, social reformer and thinker (1772 – 1890). When Enamul came across a Lalon song by accident, he felt “it expressed what I was feeling. It took me on a journey that continues today.” For him the Baul project was a personal enquiry. The focus was on Fakir Lalon Shah, though the tradition goes back farther.

The Baul 'wandering-minstrel' tradition is truly ancient, over 1000 years old, and predates Mughal rule in India by several centuries. In his Portrait of Baul, Enamul describes the Baul as a “spiritual sect of travelling minstrels who wander through Bengal from village to village, performing songs in exchange for hospitality or small rewards.”

When he first heard these songs, Enamul didn’t quite understand what they meant, but they resonated within him as the sound of home. “Despite the transient nature of Baul performances, the extraordinary qualities of their music and Lalon’s lyrics leave lasting memories with those who hear them – so much so that people of Bengali origins now living far away find them strongly evocative of ‘home’ where once they were inextricably part of the fabric of life,” he writes.

Enamul is not an academic, he’s a fan. “I don't consider myself a Lalon or a Baul expert. I think I'm a Lalon fan. I feel what he has to say is fundamentally important for all humanity.”

In a song sung by Baul Pagla Babla, recorded by Enamul, the words translated go -

Rich in rhythms and sweetness and spice,

I’m blown way out of my mind -- oh wow!

What magic is there in these songs of Bengal...

Oh wow! Oh my!

The joys of prem juri, the ektara’s pulse,

The vigours of Baul in songs and dance,

The lilting pulse of udara mudara tara,

And all in a single tune sometime!

Oh wow! Oh my!

Most nations boast a bardic tradition, where the song writers pour forth songs of nature, philosophy, devotion and detachment and, in modern times, songs of social change to the accompaniment of native instruments. In Bangla, the sounds of the ektara or dotara are haunting, and the lines that accompany them invoke great emotion.

The Bauls embrace many backgrounds - Hinduism, Buddhism and Sufism. There are images and pictures of them, says Enamul. dating to several centuries back.

“Fakir Lalon Shah was around during the times of the British, and I understand he was a bit problematic; the British probably didn’t know how to manage or control him. They probably just saw him as a fakir in a village. He was there around 140 to 150 years ago, so not as old as the Indian Baul heritage. I became greatly interested in his work.”

The Bauls were truly minimalistic, much before it became a fad, never seeking more than the next meal. Their search was for the “Unknown Bird’ – the ‘Man of the Heart’ who resides within each one of us, much like Advaitan philosophy, and clearly related the Buddhist concept of the deeper self within every individual. It is on offer for anyone who can walk the difficult path to comprehend it. The word 'baul' in ancient Sanskrit means 'madness', and their way of contemplative life is a kind of crazy, obsessive desire to find inner meaning.

Says Enamul, “It's the madness of letting go of everything that you're connected to. Letting go of your material needs, letting go of your greed. It's dancing within a tune or a song; when you close your eyes you can still see the pictures of the song. Most people are not capable of letting go because there's always something that's holding them back - whether it is attachment to family or to property or to money. We're always attached to something, so the madness of letting go is difficult to do. Only a few people can do it in their lifetime - if they're lucky! This project allowed me to let go from time to time, when I am with the Bauls three to four weeks a year over a period of two decades.” Enamul finds that Baul singers today have “a hard time surviving because they haven't kept up with modernity or technology.” See Video: PORTRAIT OF BAUL - Enamul Hoque on Vimeo

It takes six to seven years to become a proper Baul musician. “Most people who go into the Baul tradition probably don't have that many choices or opportunities. Within the Bauls there's a hierarchy - who's seen as a guru, who's seen as a sanyasi, who’s seen as a student. It's a huge commitment. I've spoken to people who come to listen to these songs and I usually find that something has happened to them in their own personal lives for which they need comfort. So the Baul perform a service to the villagers or whoever listens to them, but I don't think they are appreciated or understood in that manner.”

The songs of Fakir Lalon Shah deal with soft subjects in a very simple manner. “He tells us how to treat our mothers, how to treat oneself, how to be kind. At times, I saw the world becoming a little bit mean with capitalism and materialism changing humans. Don't get me wrong - I'm a materialist myself and I like to have nice cars, expensive cameras, expensive computers and fine clothes. What a lot of people haven’t understood is that we've been conditioned into becoming good capitalists. We've been conditioned, ever since we were born, into being good taxpayers, but we haven't been trained to really look after our souls, or our minds. This is where Lalon trains us.”

Enamul’s research started around two decades ago when he would spend a month at a time traveling across all of India, Bangladesh and Pakistan. He says the research was more in Bangladesh as his mother lives there. He has covered all the districts in Bangladesh, but not so much in India. Mostly the Bauls from India came via invitations from other Bauls in Bangladesh.

“The Bauls obviously go back and forth across the border. So they would have other Bauls who they would recommend to me from time to time. I would ask them to invite those from India to come to my home in Bangladesh. They would come and stay with me for five days or a week .”

Has the music changed across our borders? Enamul says that there is a slight difference. He hesitates, not wishing to bring religion into the conversation. “While most of the Bauls from the India side are probably more Hindu-leaning, in Bangladesh they are probably Muslim- or Sufi-leaning. I think it is amazing that these people have managed to find a safe space where they can interact and exchange ideas and have shared experiences. It has been going on for hundreds and hundreds of years, and the fact that this landscape is in clear danger of being destroyed is upsetting. My aim is to see how we can protect that landscape, where people from different cultures, with different visions or different voices, can have safe conversation without hitting each other over the head with a stick. The differences that separate us are what makes us interesting. I believe in that freedom, and I feel that freedom has been in danger for a long time.”

The songs are odes to oneness, but initially difficult to comprehend. “You have to listen to them over and over again, understand the Bangla first and then translate into English, finding the right form of the narrative. Sometimes even the people who are singing the songs, can’t fully explain or describe what they are telling us about.”

He would go back to the singers every year and it took a long time to develop their trust and friendship, “but now they see me as part of themselves.” At first, he found himself stumbling around trying to find out how to interact with them, how to talk to them, wondering how they could talk to him in ways other than the music.

Enamul says it took a while to speak the same language. “Big institutions have tried to do projects of this nature, but they have failed because they became like a dinosaur. When they dealt with these people, the relationship was never equal. While my relationship with them is not one of equals, I have tried to come down to their space, rather than having them look up to me. It took me a couple years to understand that. All of a sudden, I have become a caretaker for a great number of people, which can prove quite difficult at times.”

Not all Baul singers are the same. For some it has become a trade, to make money performing on stage and TV; those who are really concerned about Baul philosophy are few and far between, says Enamul.

It is the message in the songs, the simplicity of their lives which holds enduring appeal. “Even practicing Bauls can't understand the whole of the philosophy or live that philosophy. In some respects, I'm trying to be a modern-day Baul, almost a digital Baul, wandering from place to place, taking a few pictures and videos, expressing myself through visual imagery. Sometimes doing things even if people don't pay me.”

Enamul talks about the voice inside our heads talking to us all the time. “Experiencing Baul and Lalon has given me tools to make friends with the voice inside my head. This whole project has cost me - and others - quite a lot of money and it's taken a lot of time from me, but what it's given me in return is immeasurable.”

While the notion of the wandering mistral is romantic, it is a hard life in modern times. Enamul says that he has met many bourgeois Bangla families, both in India and Bangladesh, who feel the Bauls are amazing, “but whenever they enter their house they're always very careful about where they can go and what they can do.”

Having seen them close up, Enamul knows “these Bauls lead a very difficult life. I think if we want to have them around then we should think about building infrastructure for them to exist. Most Bauls don't have health care. They live on a day-to-day basis by begging. If we want them to exist in the manner that they do, we have to help them survive.”

It is important to build infrastructure both in India and Bangladesh, says Enamul, for them to exist either in an arts or a cultural sphere. “Sometimes they are not safe in the gatherings they have in villages. They are at the mercy of the local zamindars or local politicians, and often are not free to say what they want to say. We need people in powerful organizations to develop that safe space for them to have those conversations, because, through their songs and through their lifestyle, they raise very big questions that we need to consider - and answer.”

The project has been better accepted by Westerners than by his Bangla friends - much the same way that a lot of south Asian culture is consumed and owned. “We have to remember that a lot of non-Indians are looking at it in a somewhat academic way. If a British person came across this project, he or she would do a little bit of research on their own - about who was Fakir Lalon Shah, what is the 'caged bird'. They will do some academic research to get to the bottom of the subject so that they can fully grasp it.”

The Bengali people themselves are experiencing the music, and not engaging in intellectual research exploration, says Enamul. “For them it is a very raw emotion and because it’s Bengali, they feel it's their own. For me I had the best of both worlds. The first time I heard a Lalon song, I didn’t understand it, but I burst into tears. I didn't know why I was crying. I didn't know why it had that impact on me.”

“The only reason that I’m still around is because I went to their land so it wasn't that they came to me. I went there, I went to see where they lived. I went to stay in their shacks or their tents. I shared their spaces to sleep, I ate with them and I joked with them. If the world was perfect I would want this project to grow so that I can take them around the world. UNICEF gave these people recognition as a 'Masterpiece of Intangible Oral Heritage of Humanity' in 2005, but I think UNICEF as an organization has had a difficulty in connecting with them because the Bauls have so very different a way of being and working. They need a crazy person like me,” he says, “who's an independent creative to support them.”

CREDITS

Portrait of Baul is a project, conceived and created by Enamul Hoque, produced by Abbas Nokhasteh, and funded by OpenVizor with additional support from the British Library. Design direction has been given by Matt Moate, Technology Support by Event Projection and texts have been assembled by John Baker with invaluable help from many colleagues and friends.

Pictures courtesy Enamul Hoque