Ammini Ramachandran’s aim has been to bring the threads of history, geography, religion, tradition, and personal history together to present the vegetarian cuisine of her region, Kerala.

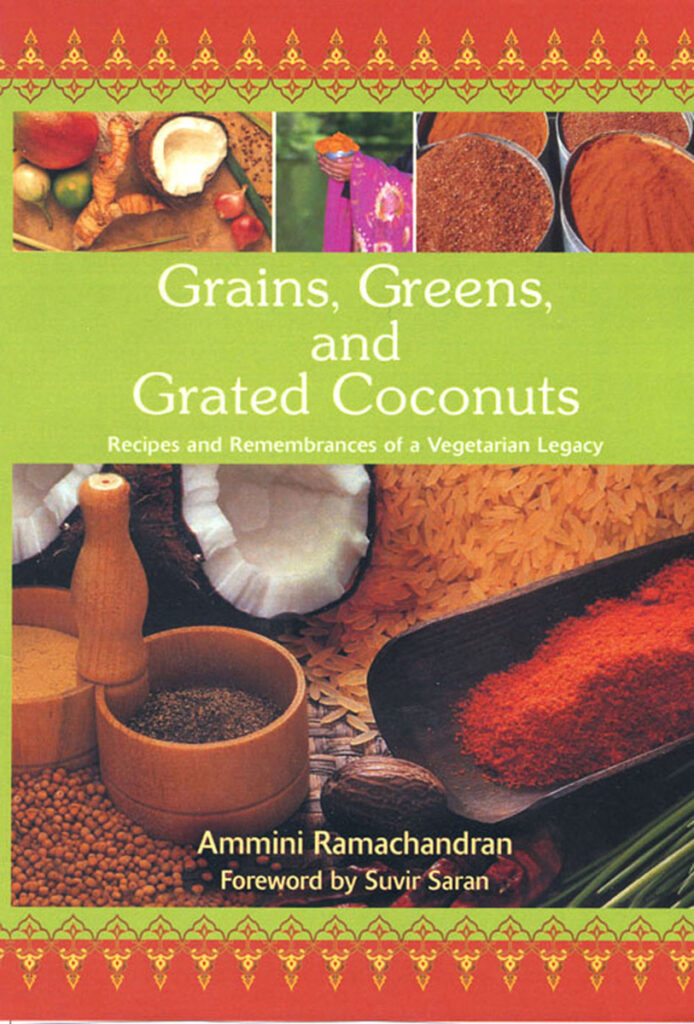

Based out of Texas, USA, Ammini is a food historian, a public speaker and an educator. She has also authored the book – Grains, Greens, and Grated Coconuts: Recipes and Remembrances of a Vegetarian Legacy, which was published in 2007.

Through her blog – Peppertrail, Ammini shares the cultural and culinary traditions of Kerala as well as the science, stories and recipes from ancient Indian literary texts. She also spoke on the Flavours and Fragrances in Culinary Traditions at the “Symposium on Indic Fragrances and Flavours,” organised by Center for Soft Power and Indica.

What motivated you to study and write about Kerala’s culinary heritage and culture?

With most of the younger generation in my family living abroad, I wanted them to remember the vegetarian cuisine of their ancestral home, its history, stories, and culture. So, I started writing a family journal, which eventually evolved into my first book Grains, Greens, and Grated Coconuts: Recipes and Remembrances of a Vegetarian Legacy.

Kerala’s history is intertwined with the ancient spice trade and the cultural, economic, and social changes it brought to the region.

I begin this book by describing the social and cultural aspects of the joint family I grew up in, the matrilineal system of descent, temple festivals and seasonal festivals, and the celebration of the life cycle.

The first chapter – Our History and Heritage, presents a brief account of the development of the ancient spice trade that began before the birth of Christ and lasted many centuries, greatly influencing our society. I elaborate on the social and cultural diversity of Kerala; its gradual colonization by foreign traders, including the Portuguese, the Dutch, and the British; the unification of Kerala after India gained independence from the British; and the influences of foreign trade on our agriculture and cuisine.

In the next chapter, I talk about ingredients, utensils, and cooking methods in a detailed manner, which is then followed by many recipes from the land.

Kerala cuisine is known for its varied non-vegetarian food and strict vegetarians are a minority in Kerala. Many of these simple vegetarian recipes were not documented and my attempt was to document them. The recipes are mostly satvic, except for two or three that use onions.

How can one understand the evolution of India’s culinary heritage over time?

While researching for my book, I read several food-related books for guidance. I came across K. T. Achaya’s magnum opus, Indian Food: A Historical Companion and it was an eye-opener for me. Ever since I published my book, I have spent hours researching and writing about the history and evolution of Indian cuisine on my website.

The cuisines of ancient India were deeply rooted in ethical and medical principles. Ancient texts also discussed various aspects of food from the perspective of Indian herbal medicine Ayurveda. Another major feature of these works was they compiled a lot of information from earlier works.

During the early medieval period, regional kingdoms of India were flourishing and kings, as well as temples, were decisive shapers of regional cultures. Literature enjoyed generous royal support and patronage. Many culinary texts were authored by kings themselves or by their court poets and the food described them was not always the food of the common people.

The cooking processes described in the ancient texts are elaborate, time-consuming and labour intensive. Cooking was done mostly on wood-burning stoves.

What I found most fascinating was that in earlier times though content with native ingredients, ancient cuisine went out of its way to treat, transform, and prepare them in a variety of ways. These recipes speak volumes about the expertise in high-class cuisine that was prevalent in ancient India. What was equally fascinating is the fact that the new spices, plants, and ingredients that later arrived through the trade routes, were all completely integrated into India’s agriculture and cuisines.

The foods, techniques, and culinary heritage of the past should be certainly recorded and preserved. While reviving them in their original form may not be practical, adaptations of some of the recipes and techniques could certainly be done.

What makes Indian gastronomy distinct from others in the world

The complexity of Indian cuisine and the masterful use of spices work together to bring to the table the best of India. While dishes vary by region, the typical Indian dish contains several different ingredients and an infinite array of fresh spices, each bringing its own unique aroma.

Another thing that sets Indian food apart is its use of whole spices instead of powdered ones. Indians are experts in combining herbs and spices. Most Indian cooks take pride in their very own spice mixes.

How did India’s spice trade influence its economic and cultural relations with the world?

Ever since ancient times, the monsoon-soaked rain forests of south India, home to several spices—including the world’s most widely used spice, black pepper—were a prime destination for many explorers. The abundant black pepper attracted Arabs, Greeks, Romans, Portuguese, Dutch, and British from the west and Southeast Asians and Chinese from the east.

Despite the fame of overland trade along the Silk Road, much of the significant trade between Europe and Asia was carried out in specific sailing seasons along the Indian Ocean. The pre-Islamic tribes of Central Asia, along with Indian and Southeast Asian merchants, were active traders and intermediaries in the early Indian Ocean trade.

Along these trade routes, they collected silk from China; cloves, nutmeg, pearls, and tortoise shells from Indonesia; and cinnamon, ivory, and tortoise shells from Sri Lanka. These commodities were transported to Muziris and other ports along India’s southwestern coast. Muziris became one of the main trans-shipment ports for goods from the east. The most important was pepper, which was always shipped as a large bulk commodity; followed by cinnamon, ginger, and cloves.

Spice traders took these native spices across the great expanse of the Indian Ocean to Africa and Arabia, and from there, to points farther west. The tradition of maritime trade expanded to unprecedented levels with the introduction of spices to the West.

It is impossible to fathom the economic benefits to the nation as a whole from the export of spices. The spice trade not only influenced cuisine but also left an indelible imprint on our culture. When foreign traders arrived at the port of Muziris, near the capital of the Chera kings, the reigning kings treated them with respect, extending facilities for their settlement and the establishment of their faiths in the land.

Could you tell us the importance of pepper in the spice trade?

For almost 2,000 years black pepper dominated world trade and played an important role in promoting trade between the East and the West. Pepper was known in Greece by the 4th century BCE and was an integral part of the Roman diet by 30 BCE. It remained a force in Europe until 1750 CE.

Before the days of refrigeration and the invention of other methods of preservation, pepper and salt were the only preservatives available to man. During much of the Middle Ages pepper was considered a symbol of wealth and affluence. It was a status symbol of fine cookery and a description of a lavish feast invariably mentioned pepper, if not other spices.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Arabs held the control of spice trade for a long time. In the 10th century both Venice and Genoa began to prosper through trade in the Levant. Over the centuries, a bitter rivalry developed between the two that culminated in the naval war in which Venice defeated Genoa and secured a monopoly of trade in the Middle East for the next century. Arab traders took their merchandise to Alexandria and the Venetians dominated in the distribution of pepper and other spices from the Mid-east to Western Europe. Major market centers were Constantinople and Alexandria.

From the 12th to the 17th centuries, spices constituted the most profitable and dynamic element in European trade and Venice made exorbitant profits by trading spices with buyer-distributors from northern and western Europe. With these monopolies, pepper prices skyrocketed and only the rich were able to afford it.

Although the origins of spices were known throughout Europe by the Middle Ages, no ruler proved capable of breaking the Venetian hold on the trade routes. The higher prices frustrated other European nations and towards the end of the 15th century, the Spanish and Portuguese began to build ships and venture abroad in search of new ways to reach the spice-producing regions. The famous Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama arrived in Kerala in 1498 A.D. This marked the beginning of the Portuguese dominance of the lucrative spice trade from India. This totally ended the Arab and Venetian monopoly of the pepper trade.

Besides playing a key role in trade, how was pepper used in the social and cultural lives of people?

The consumption of pepper grew astonishingly in the days of the Roman Empire and pepper became the most typical spice in medieval Europe.

Pepper was equivalent to money and people stored it under and lock and key. In 408 A.D. when Alaric, the King of Visigoths, besieged Rome he demanded a stiff price for sparing the city, which included fine garments, gold, silver and 3000 kilograms of pepper. A “proper bribe” from a merchant in Venice to a tax collector included among other things a pound of pepper. In the early 11th century, King Ethelred collected tolls in the form of bags of pepper from ships that landed at Billingsgate. In 1101 A.D. soldiers of Genoa were rewarded with one kilogram of pepper each for their victory in a war.

One of the oldest guilds in the City of London is the Guild of Pepperers, registered as Grosserii, or wholesalers, in 1328 A.D. And in France, a pound of pepper could free a slave. In Germany, a nickname for the rich was “pepper sacks”. When an English ship that sank in 1545 A.D. was raised from the ocean in the 1980s, nearly every sailor’s body was found to have a bunch of peppercorns, the most portable valuable, in his possession.

In Renaissance Italy, pasta dishes served at banquets were sprinkled with abundant quantities of black pepper and cinnamon, as a symbol of prosperity. Around that time, miniature ships of precious metal, inlaid with gems and filled with spices were used as table decorations. The princely houses of Europe had developed a passion for pepper that led to ostentatious display. In the 15th century, Charles the Brave of Burgundy had 289 pounds of pepper brought to his table for his wedding banquet.

As a food historian, you have studied and revived many ancient Indian recipes. Do you have a favourite recipe?

My favorite ancient recipe is a simple side dish made with fresh pomegranate. It is from a poem in the ancient Sangam literature of South India that dates back to 300 BC and 300 AD. These poems started as an oral tradition, and several were lost. In the 19th century, poems written by 473 poets were collected and published in ten volumes of longer poems, Pattuppattu (Ten Idylls) and eight volumes of short poems in Ettuthogai (Eight Anthologies).

In one of the oldest poems, Perumpaanattuppadai, in Pathuppattu a bard recommends to his fellow bards to seek the help of his patron, the ruler of Kanchi. The poem graphically recounts the things the bards would see and get to eat as they travel through various landscapes on the way to the capital city Kanchi.

He tells them when they get to the Brahmin settlements at sunset, they will get well-cooked rice that bears the name of a bird along with fresh pomegranate cooked with butter made from the milk of red skinned cows, fresh curry leaves, and black pepper along with fragrant pickles made with tender green mangoes.

Although it is not practical to get butter from the milk of red-skinned cows, this simple recipe that combines the slight tartness of pomegranate, citrusy notes of curry leaves, and the sharp spiciness of black pepper, is simply delicious.