Sisters know and experience the nurturing dimensions of the same womb. Years later, when and if they pursue the arts, together, as learners

and performers, seekers and shapers, they revisit the experience of the womb of a different kind and fibre. The womb of the sacred arts. Dimensions occur to them in the same or different spaces, but they bring their own interpretations to art. Natalia Salgado and Patricia Salgado are dedicated to the propagation, teaching and performance of the classical dance forms of India in South America and Europe.

Their project and centre Güngur - based in Argentina and Spain - has institutionalised the imparting of training and performance of the Indic classical arts, collaboration, composing, and helping creators and learners connect with Indic knowledge systems through dance. The sisters share a bond of shaping one initiative, two nodes of the same institution on different lands, audience and students based in two countries, a direct engagement with the arts in three continents and a thriving audience.

They would select “Güngur” as the name for their cultural centre (its two shoots) in Argentina and Spain, signifying their bond with Indic aesthetics. The symbolism in the name is intrinsic to their journey. It reflects the unison and synchronicities in sound, creation, performance, the practice and propagation of Indic arts.

At the core of their work and creative process are three Indic dance forms: Bharatanatyam, Kuchipudi and Odissi. India, the source of their

art, their spiritual destination, is home to their gurus.

The inner spaces of Natalia's solitude with art are enveloped in the memory of India and her gurus. These memories surround her present

moment. Her memory and recollections are bound to the constant measure of laya and tala. They are cyclical. Rhythm sets her in motion with moments from the past that have contributed to her learning, practice, the emotional process of gathering the sights and sounds from India.

Natalia’s mindscape is attuned to the realisation of memory in dance in an indestructible connection with the touch, textures of fabrics and crafts that enrich the arts. The silk of her costumes brings to her present the memory of Mylapore (in Chennai). The diverse accessories, the gentle bearing and sweet sound of the ankle bells she endearingly addresses as “gungur”, become ‘vehicle’ of her travels to India, in thoughts or in the physical covering of the miles between the two continents. “Gungur” - the ankle bell tied to the dancer’s feet and her rhythm, would become synonymous with the identity and efforts of Natalia and Patricia in the propagation of Indian performing arts.

Inseparable is the dual force of nostalgia and memory and its penetration into centuries of creation synonymous with preserving wisdom. For Natalia, dance overpowers the “remoteness” in every offering of performance set to motion, rhythm and the sound of the ‘mardala’ (percussion instrument). As Natalia herself shares in one of her writings, the touch of silk (of costumes) on her fingers leaves gentle traces of journeys that have woven her bond with India.

She writes in one of the blogs: “I remember the little ‘gotipuas’ dancing and hanging around, the great Gangadar Pradhan saying to me and my sister ‘practice, practice’, the smell of that small kitchen, the dance hall with little light and the mardala marking our steps. I remember our wet sarees, our effort and our big smiles (sic).”

Memories of her training-years in India, where she surrendered herself to the practice of Odissi, Bharatanatyam and Kuchipudi, come fleetingly when she is moments away from entering the performing dais. At this moment, she is continents away from India, yet the ritualistic connection with memories - of how she learned a piece, builds up quickly in her mind.

One is tempted to wonder what the existing opportunities and/or platforms for watching, learning and exploring the arts were in Argentina when Natalia’s interest was soaring for the Indian performing arts. Natalia tells us that there was none -- until 2001. In order to perform without hindrances, to overcome the lack of or unavailability of helping hands adept at stitching and designing traditional costumes, Natalia and Patricia stitched their own costumes. So profound is the fabric of surrender to the Indic arts, Natalia’s artistic thought got threaded to every activity required to make ‘performance’ possible, meaningful, vibrant.

Years of dedication to the Indic arts came to them from two different tributaries of the same river.

The second tributary that shaped their course was the iconic Myrta Barvie – world-renowned Argentinian dancer who created the path for

Indic arts in Argentina after connecting Latin America with India for a timeless with the land and her learned. She was 17 when her iconic

performance in Argentina would be followed by the life-turning visit to India, for and to Kalakshetra.

Myrta’s contribution to the propagation of Indic culture is not only defined by her own prowess[s1] in the arts, the technique she developed with her practice of the dance forms, her body of work, but also in her efforts to expand the base of “viewing” performance. Her role in connecting the propagation of the sacred arts to the exploration of beauty as a pursuit -- with performers who speak different languages in their verbal and visual expressions -- is an ode to the Indic feminine beauty and the feminine body. Its value to two different cultures she bridged in the arts can be felt in the current work and efforts undertaken in Güngur. The centre is the direct outcome and an indirect extension of her own success as a guru.

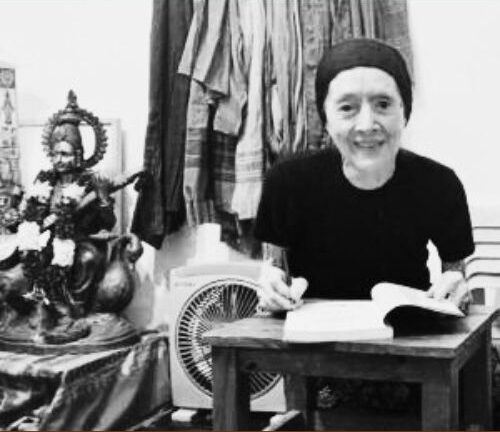

The timelessness of Myrta’s contribution is well-represented in photographs shot in India during her learning years with her great gurus. Her image provides a moving foreground to architecture and the visually-engulfing geometry and perfection of the chakras at the temples she has visited.

Myrta, as seen in the static postures over those moments, represents a tradition that has redefined past, and ‘presence’ in the sense of time, also signifying the motion of the wheels of creation and creativity that the feminine sets in form, geometry, and memory. There are other stills showing her engrossed in her lessons and performance. These are valuable residues of her complete surrender to knowledge through dance as journey and destination.

These stills give a glimpse of moments, hours and years spent in gaining wisdom from the gurus. Meeting Myrta exposed Natalia to a philosophy in expressing life and beauty in dance. More importantly, she was guided to the path and process to meaningfully seek ‘the

Indic’ in India and in the land of her birth through the arts -- by Myrta herself.

Thus, two different generations of dancers from Argentina would give Indic arts new platforms, new practitioners, new learners, -- feet,

mind, imagination and interpretation.

In their efforts to sculpt their creative appetite, artistes born outside India travel great distances to overcome geographical barriers, language hurdles and cultural boundaries. In the case of Natalia and Patricia, their journeys as siblings gifted a new vision for performance. For the learning of the dance forms, they took a courageous leap across material circumstances that were always not aligned with their needs as performers, or their requirements as artistes.

Their performance, teaching and learning of the Indic dance forms, are offered to an audience that often makes that first attempt at connecting with ideas, devotion and perspectives on the divine – which are inseparable with the sacred arts. The audience’s perspectives may

not always be aligned to the viewing of the performing arts from the devotee’s eye. They are not always birthed by a vision nurtured or trained to the viewing of the performing arts as a fountain of the celebration of the temples, temple architecture, music exclusive to the celebration of the art form or the deity. This is where Natalia’s role in connecting with the Indic, the Indic “classical”, devotion to

the deities, India and India’s soft power, comes in.

The archival value of Natalia’s performance bears the heightened emotive response to a civilisation which is not their own, but a civilisation discovered over the individual effort in a unified response to the arts. These arts themselves become subject and medium of exploration of the civilisation. They infuse life into the portraits of artistes, who, in the process of becoming one with the art, mingle and merge into two different and distant landscapes – the landscape where art has shaped over the centuries, and the other landscape, where it surrounds new efforts in preservation of the ancient belonging to the “other”.

As an institution, Güngur is not just another performance or learning space. It is a banyan tree of confluences supporting vibrant art ecology. It is home to interactions in the art where costumes, themes, subjects that offer a diversity of themes, music, musical instruments, and different bodies of work shaped and constructed with sweat, Indic aesthetic-oriented composition in dance and music, exist in collaborative demeanour. If dug deeply and directly, each journey in the performing arts at Güngur would present a personal diary in creative discoveries that are connecting with new audiences in Spain and Argentina.

She has trained more than 100 students over the meticulous process of weaving an art-inspired relationship with India. Her belief in the guru-shishya system of learning for the preservation of the Indic performing arts is felt in how she encourages students to travel to India to learn from the gurus -- after she has imparted the basic lessons. She also encourages institutional collaboration under Güngur as her “project”.

The soft chaos of the buzzing traffic in Buenos Aires is an aspect easily subdued and overpowered by her immersion in practice. The scenes of Argentinian urban life, visible from the practice-space at Güngur, and the moments that go into the performing, learning, teaching and fining of steps, stance, vocabulary and grammar making Kuchipudi and Bharatanatyam, are portions of the two worlds she has brought together. A depiction of Natraja looks over the practice space. Also present is the divine depiction of Jagannath, Balbhadra and Subhadra -- deities central to Indic devotion and devotees in Odisha, and the vast fraternity of preservers of the sacred arts. At Güngur, the divine presence of these deities seems to extend a spiritual purpose to the dancers, who have, or one day, will, follow their devotion, creative instincts and response in the arts, by walking to temples that are abodes to these deities -- in India.

Natalia has a unique way of looking at Indic performing arts. It is: dance as a communication with body, postures, balance and stance. The

slow and gradual process of learning steps and technique became “a way of life”. The nritta aspect of Indian classical dance forms would become a point of focus in Myrta’s art and practice, and develop into a facet of tradition that Myrta carefully-moulded in training Natalia.

India exists in every frame, every corner, of Natalia’s practice space. The interpretation and meaning of ‘foreign’ and ‘own’ get rearranged in this room each, with or without the presence of its occupants. Dolls and textures representing Indian handicraft and weaving; a framed photograph of Gotipuas; other objects signifying India and ‘Indianness’-- are glimpses intrinsic to her own journey. Gotipua-life finds fond mention in her recollections of India.

Natalia works on her own art; trains dancers over recollections of her own lessons under the guidance of her gurus in India. The milestones

in shaping her disciples’ practice are marked by memories of her learning in India. With a belief -- that the proof of practice resides in the quality of the sound of the ‘ghunghru’, she continues to teach and learn, learning from teaching, teaching as she learns, in order to achieve that finest moment and their finest sound. In an email interview with Sumati Mehrishi, she delves into her journey as a practitioner of the Indic dance forms in Latin America and Europe.

1) When did you get the first glimpse of Indian art, Indian performing arts and expressions, and what impression did they leave on you?

It was in 2001. I saw my first guru Ms. Ranga Vivekanandan performing and I thought it was the most exquisite art form I had seen in my

entire life. Sophisticated, elegant, dynamic, I felt in love immediately.

2) What aspects of Indian dance forms, music and expressions drove you towards learning and exploring them?

The sum of all these aspects drove me towards learning and exploring them. When I started learning the first steps, something inside me

burned with flames of enthusiasm. I could not believe that so many aspects could become part of one single training. I love exploring

rhythmic patterns.

3) What does ‘Indian aesthetic’ mean to you?

It means (an amalgamation of) visual, artistic, and design elements that are characteristic of Indian culture and heritage. I also define it as a way of passing by history through a singular way of presenting ourselves -- before dancing. I feel that when we ornament ourselves, when we put on our costumes, when we put on makeup, when we select colours we use (in presentation and performance), when we wear the costumes and accessories, we become somebody else. I forget about myself and connect with the history, believing that the same costumes

and ornaments have been used for decades. I energise myself with all these thoughts and reflections before coming to the stage.

4) How did meeting Ranga Vivekanandan ji change the course of your life and journey in Indian performing arts?

Ranga ji was a pioneer in Argentina. She was the first one to teach, share, and patiently instruct on Kuchipudi. For us, dancing was quite

easy in the beginning. We found difficulty in learning the steps, but we could go with the flow, as if we had dance in our blood. Dance

became an ally. It showed and keeps showing me exactly how I am, the things I can do the right way, the things I need to focus on the most.

It opened a whole new world of possibilities.

When I started learning Kuchipudi, it was a hobby. I used to work in a multinational company, and for many years, I built a professional

career. However, after my first trip to India, I connected differently with dance and felt that I needed to share the art with others like me

who were seeking “an ally” in life.

5) Please tell us about the contribution of maestro late Myrta Barvié to your learning and performance.

Myrta ji was the greatest mentor we could ever dream of having. She told us the real story of classical Indian dance lived by her own body. As she had studied dance from Smt. Rukmini Devi, Master Kelucharan Mohapatra and Master Vempati Chinna Satyam, she advised us on where we should study dance when we visit India. She encouraged us to travel. She presented us to the Indian Embassy in Buenos Aires. She

instructed us on how to demand rights as dancers, and most importantly, she inspired us to develop respect for the artforms and respect the artforms - always.

6) Myrta Barvié ji shared a profound relationship with India, Kalakshetra, and contributed immensely to Bharatnatyam, its learning, performance, and propagation in South America. How did her connection with the two cultures, people and traditions, get passed on and help you as a performer?

When I met Myrta ji, she had already stopped performing. I believe that in learning from her, we became her ongoing mediums to dance and

her continuing practice. Through us, her disciples, she could choreograph, she could go out on stage and present the items to be performed. She came to our rehearsals, she advised us on the costumes to wear, and we had meetings, where she shared her stories and knowledge. When we opened schools to teach, she encouraged and supported us to pursue the arts with the mission of expanding classical Indian dance to western culture.

Myrta ji wrote two books, the first one, “India and its classical dances” in Spanish. She also wrote a beautiful novel. We helped her a lot in achieving her own goals. We were like daughters to her.

7) Share with us some memorable moments of performing at Myrta Barvié ji's dance company.

She admired my technique and said I was a fast-learner. I used to perform “Ganapati Koutuvam” -- a wonderful item in Kuchipudi. She loved it. Every time I perform this piece, inside my heart, I am dedicating the performance to her. Oh, there were so many memorable moments. We performed together for many years. There are fond memories of having dinner together in an elegant hotel room after a performance. It was a room she demanded, strictly, so we could change properly, and then she asked for room service! She was great.

8) You have learned Bharatanatyam, Kuchipuddi, and Odishi. Why did learning the three forms become important for you in your journey as a dancer and artiste?

Through the years, I understood that I not only wanted to become a serious and committed practitioner of dance and tried to perform properly, I found great pleasure in teaching. It seems as if it is part of my mission in this life. Learning three styles gave me all-rounded knowledge of the basics and technique. The art forms are very different from each other and they are suitable for different bodies and different souls. Knowing this, I can advise students on the path to follow in dance. Some students are more suitable for Odissi because of how the energy flows. Some students are more dynamic and more aligned with Bharatantayam. I teach the basics and encourage them to continue on the path with the renowned masters of India. To me, as a performer, the basics of the dance forms have been complementary.

For example, the torso that we practice so hard in Odissi has been of great help for some steps in Kuchipudi. The‘bangis’ that I am able to

perform are so much better with this technique.

9) Bharatanatyam, Kuchipudi, Odishi, bring different realms of grammar, postures, body stance, percussion, musical composition and music. How do they flow into your dance journey when you are thinking composition and choreography?

In Argentina, when I have to work with musicians, I always choose Odissi because we have mainly sitarists and tabla artsites here. Carnatic music is not so developed in my country. However, when I have to do rhythmic compositions, kuchipudi bols and jathis come immediately to my mind and inspiration. Also, according to where I am invited to perform, I choose the style. For example, if it is a big festival and I have little time, I probably would choose a Bharatanatyam item. If we are invited to perform in the Ratha Yatra, I will choose a Kuchipudi or Odissi item. They are longer, but the public has the patience to appreciate a full, long, piece. Knowing the three styles allows me to do beautiful jugalbandis (and) between them (the dance forms).

10) Güngur brings up and hosts an exciting mix of different facets of Indian art, performing arts, Yoga, spirituality, cinema and culture. What prompted you to build a platform and audience for multi-faceted viewing and absorption of Indic culture, heritage and knowledge systems?

Being an entrepreneur in Argentina demands you to constantly keep changing, evolving, adjusting and reinventing yourself to keep on truck. Otherwise, the country and its difficult economy push you to move in another direction. I have always been creative and having a corporate background gives me tools to run Güngur.

Also, many professionals have reached out to me to offer their experience. I help them expand their work. These include photographers, art directors, musicians, language specialists, Ayurveda and Yoga professionals. So many people come close to Güngur. As (the person behind) a cultural centre, I have the mission and responsibility to give them all an opportunity to showcase what they do. Having a restaurant inside Güngur attracts lots of people and most of these wonderful experiences are completed by tasteful gastronomy.

11) Why is it important for dancers to connect with Indian thought, Indian sacred texts, spirituality; Yoga, and food?

It is important because this is actually the source of what we do. We need to understand, study, and connect to the tradition in order to

translate it through our own bodies. The steps are to be learned and mastered, but what reaches the audience, goes beyond the technique.

The inside world of the dancer has to be beautifully-fed with love and knowledge for this ancient and rich culture.

12) Two destinations in two different continents – that’s a vast geography bridged by Güngur and Spanish. How do the staff, artistes, students and audience connect with each other and how does Spanish help in the cultural-bridging?

We learn a lot from each other and we understand that Argentineans are different from Spanish people. India is closer to Spain. The (aspect

of) exotic in Argentina is not there (in Spain). So, the proposals are different for each country. Regarding students, as dance is a common

language, we really enjoy collaborating and supporting each other. My sister Patricia is a wonderful designer. She brings beauty to all

images of Güngur. Social media and events like the congresses that we have been doing for three consecutive years, offer the possibility to

interact with the extended Güngur family.

13) What do the staff, artistes, students and audience, think about India as an ancient civilisation and a parent cradle of the knowledge systems?

We all love India deeply. As if she is a mother for all the countries of this world. India takes care of humans by teaching how to breathe,

meditate, do Yoga, understand our bodies, and eat well. Regarding dance, India has given to history the source of all dances. Everything

is involved in a classical Indian form, and even though we are very far away from India, when we perform here, the audience gets to

connect with the ancient civilisation.

14) Tell us about some of the memorable interactions with Indian artistes who have visited Güngur.

I remember hosting Ms. Sarita Mishra (an exponent of Odissi performance and preservation) at my house, after my second baby was

born. We were all running around like crazy people playing with the babies and trying to do rehearsals for a performance. I also remember

having a wonderful conversation with Dr. Janaki Rangarajan about my concerns of being a dancer and mother at the same time. I have

experienced and shared many beautiful moments in my interaction with wonderful artistes. I believe this is the universe saying: ‘Hey, nati!

Continue, you are on the correct path.’

15) Do you aim to connect the Indian audience with Güngur dance repertoire?

Yes. I have a dream and maybe, one day, this dream will become true. I have never performed in India - on a stage. I have travelled four

times, but the moments spent there were mainly to study and learn as much as possible. So, yes, before I am too old to perform, I would

love to dance there one day. Meanwhile, I try to do online events, so my students can share dance (and performance) with the Indian audience.

16) How often do you visit India and what do you rediscover about yourself each time you visit India?

I have travelled four times: in 2007, 2009, 2012 and 2014. In 2016, my first baby was born. I could not travel after that. Now, I take classes virtually, so it helps a lot. Each time I visit India, I reaffirm that I am doing the right thing with my life. As if a part of me belongs to this ancient civilisation and I am just following indications to expand the civilisation’s beauty in South America.

17) Which expressions of Indian visual art draw you towards form, aesthetic, and posture?

I have to mention the ‘karanas’ for Bharatanatyam and the sculptures of the Sun Temple in Konark. Pathfinder, a book on Odissi, contains

drawings of dancers performing still points and mobile points. These have inspired me a lot.

18) Does the celebration of the Divine Feminine and the feminine in the Indian classical dance-forms appeal to students of Indian classical dance in Argentina and Spain? b) What role can this celebration play in connecting audience to Indian dance forms, story-telling and themes?

Yes, absolutely, themes related to the Divine Feminine and the feminine experience resonate with people from various cultures, as they often explore universal emotions, relationships, and human experiences. These themes can evoke empathy and understanding in students and audiences from different backgrounds. Themes related to the Divine Feminine add depth and emotional resonance to these stories, making them more captivating and relatable to audiences worldwide.

19) What is the most valuable and long-lasting aspect of Indian soft power?

I believe that it is cultural heritage and diversity. The cultural richness has a profound impact on how India is perceived and admired globally. I can tell you from my experience. Each Friday, I host approximately 30 people at Güngur. Some of them, maybe, know a little

bit about India, others do not. The minute the music begins and the dancer appears (on the dais), their mind forgets about what they were

doing earlier, they forget about their concerns and their problems.

For a few minutes, they become one with the dancer and the tradition, passing by with a movement, a hstha mudra or a swara. After the performance, they sit down and eat a samosa, a navratan korma, and a pistachio burfi. These flavours invade their hearts and bodies with

spices that travel from so far away. These 30 people leave Güngur with smiles on their faces, they have travelled to India for a little while

(via the performance), the tradition and the richness will reach their souls and bodies.