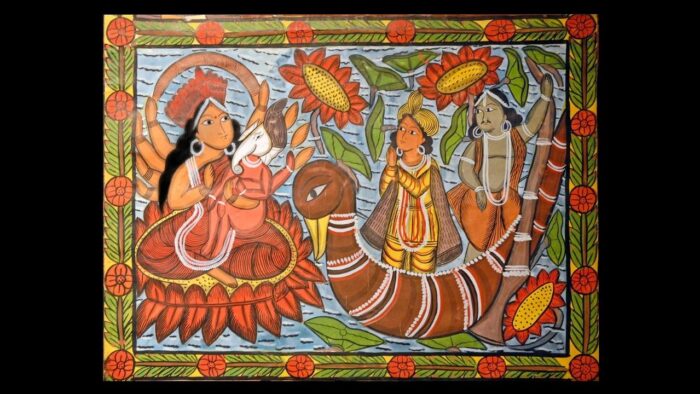

The wisdom of the ancients was passed down from one generation to another through stories. Indians have used various forms of art to make sure this wisdom was never lost. Each region in the country developed its own mode to portray different kinds of stories. Tribal and folk art in India are till date repositories of knowledge of ancient traditions, events, festivals and more.

Indigenous tribes protect and maintain the last few remaining pieces of wilderness. Tribal art is empowering because it enables a diversity of voices. In communities that lack a written form of language, art helps to voice out and share knowledge.

Tribes from different places in India shouldered the responsibility of keeping our rich culture and heritage alive. They drew narratives from the epics, Puranas, nature, the day-to-day activities, and other travellers. Some forms of folk art were also accompanied by music and dance. For instance, Pattachitra art of Odisha. Those days the king commissioned the paintings. He would ask for two sets; one would be for the palace, and the other would be given to the community. Each vocation would be given one scroll, and at night, the community would gather to listent to the stories. The potters would narrate the story from the scroll given to them. Then, the weavers would narrate from their scroll and the whole community spent precious time together, knowing and understanding the Ramayana, Mahabharata and more.

Many of the artforms date back to two thousand years and it is heartening to see some of them alive till today. Artists not only drew inspiration from nature but made sure that they used natural resources to make their art. This made sure their art was eco-friendly and sustainable. That was the wealth of knowledge each artwork possessed.

Another sustainable folk artform is Tholu Bommalata from Andhra Pradesh which originated more than twenty centuries ago. Made from antelope or goat skin, the puppets are placed behind a screen such that the audience are able to only see the shadow of the puppets. Each body part of the puppet is separated by leather and joined together by a thin cotton string. The Sutra Dhar or the puppeteer holds them on a cane stick. The entire puppet is filled with holes of varying shapes and sizes, so that light can pass through thereby producing an effect of lights and shadows.

The play with lights and colours definitely sounds incredible. What is more incredible is how the puppet makers achieved the right colours for different characters. Hues of blues were used for male characters like Rama and Krishna, while tones of orange and red were used for females.. The puppets were also varnished with either coconut oil or neem oil and this helped in the preservation of the puppets for years.

Stories from the Ramayana and Mahabharata were depicted using these puppets. Today, the puppeteers use these puppets to showcase other aspects such as environmental issues. One other form of folk art, which was showcased in Glasgow Museum’s World Culture collection, is Warli art.

Warli art is a folk art that originated in the Warli region of Maharashtra. The artform uses geometric patterns to depict the lives and beliefs of the Warli tribe. Warli paintings were depicted on walls, especially during special occasions like marriage. A very striking feature of Warli art is that one can see a spiral chain of humans around one central motif. This signifies that cycle of life, and that it has no beginning or no end.

A Warli artwork by Rajesh Vangad was one of the many indigenous artworks from across the world that was exhibited in the Glasgow Museum of World Cultures. This was later chosen at a panel discussion on Ancient Knowledge and Modern Thinking: Climate Perspectives in Folk Art. Rajesh Vangad presented his artwork along with a short film on Warli art. His work specifically focused on the effects of climate change.

The Warli tribe live in close proximity to Mumbai, and this impacts on their way of life, their environment and health. Rajesh in his artwork depicts urban landscapes such as skyscrapers and other tall buildings, and he also expresses the allure to big cities by portraying his community walking towards Mumbai by foot. In all of his portrayals of urban life, he has made small representations of nature. This to say that nature is not just in faraway places but is in close proximity to us. Rajesh has also shared health messages in his artwork by illustrating the large coronavirus, face masks, and hand-washes.

Prof Advaith Siddharthan, one of the panel members at this discussion, is a professor of computer science with his research interests lying in citizen science, artificial intelligence and data science. At his university, they explore methods for informal learning and knowledge sharing, especially through citizen science. The university have set up a unique platform known as iSpot for sharing records and knowledge around biodiversity.

They have looked at cities and science from a data perspective, recorded and monitored the environment, and quantified the benefits to the environment and the economy. Prof Siddharthan pointed out that, while doing so, they have missed out on opportunities to engage with people associated with nature at a more emotional level. Currently, they are looking at ways in which arts-based methods can be incorporated into citizen science.

For instance, if a herb garden or a wildflower meadow is planted in a school, a whole new sensory experience in school is developed. Besides, this also creates new opportunities to learn science outside classrooms. Now, if the students observe a particular type of butterfly in the garden in a particular season, there are many ways to record that data. An illustration of the butterfly creates an emotional attachment to it when compared to clicking a picture. So arts can act as a bridge that connects science and its societal relevance to the public.

Today, in the Indian Institute of Sciences, one of the topics offered for the undergraduate students is ‘Mapping India with the Folk Arts’, where they explore indigenous knowledge with a focus on the different forms of Indian Folk Art. The humanities subjects were incorporated in the academic curriculum of IISc, when the Bachelor of Science (Research) programme began. The institution believes that these subjects provide a socio-cultural background to learning and understanding science. Students have used folk art to present complex scientific concepts in their assignments. Some of the folk art traditions that were used are Dollu Kunita and Chittara art. Theatrical performances were also held such as “Sway with Science”, and “Jal Jungle Zameen and Science”. Indian folk arts not only relay stories of the past, but also play a role in science-storytelling, making it more fun.

Even though the challenges of the current day seem large and intractable, Prof Siddharthan believes that by taking small local actions with the help of these arts-based methods, they can empower people, and cumulatively, these actions can make a difference.