TTB - Teatro Tascabile di Bergamo - is a theatre company in Italy founded by Rezo Vescovi in 1973. It is housed in the former Monastero del Carmine, with a fading, rundown facade. When Indian Bharatanatyam dancer Praveen Kumar entered the ancient monastery with trepidation, little did he envision a beautiful theatrical laboratory with a library with rows of Indian theatre-dance texts including the Ramayana and Mahabharata, 12th century poet Jayadeva’s Geet Govindam, the Natyashastra and the Mahakavyas.

Vescovi was highly influenced by the techniques and theatrical tradition of one of Europe’s greatest theatre directors, Poland’s Jerzy Grotowski, who was so connected to India that his ashes were brought to India and scattered on Arunachala Hill.

Grotowski was a leading light of theatrical Avant-garde movement of the 20th century. His mother gave him books to read and among his favourites was “Search in Secret India” by Paul Brunton. He was instrumental in creating the notion of ‘poor theatre’ – literally meaning stripping away the unnecessary, leaving the actor standing on his own.

Author Viktor Adorjan in his book on Grotowski describes his life in India in 1970. During his stay, he had kept notes and in one he says, “let us touch the state of the human being where one is not divided into body and soul, thoughts and feelings, active creator and passive receptor thereby giving the possibility for all to drop the masks of everyday life.”

Greatly influenced by Grotowski, Vescovi guided TTB eastwards. In one corner of the monastery is a tamburi, in another a mridangam and on one side is a traditional manjira. Theatre artist Tiziana Barbiero sits reciting the Ashtapadis, which she knows by heart, learnt with the meaning, so “as to be able to articulate the bhava. I can’t dance Odissi without knowing everything about Jayadeva’s Geetha Govindam,” she says.

Praveen who teaches two Italian actors - Alessia Baldassari and Caterina Scotti - says, “In their theatre it is not just about learning the art form but about being aware of every aspect of it. Though they are away from India and working with their respective teachers, they are constantly in an ambience of that particular art form.”

Tiziana Barbiero says traditional European theatre relied heavily on texts with the actor only speaking and not moving the body. “So we were fascinated by this ‘strange’ Indian theatre where they were not using texts, but were working on the body. This was very attractive to us because we had a great hunger not just for technique but also the ethic of Asian theatre which required the negation of the individual ego in favour of the artistic work. Spirituality for us is the keeping away of the ego of the actor. This was something very different from our theatre culture.”

Having grown up in a convent till the age of 14, Tiziana says that for her the stories of Christ as a child are not very different from that of Krishna. “So there are always things that you can relate to from your own culture and transpose into another one. We study Indian spirituality for the dance. ”

A big UNESCO sponsored festival held at Bergamo in 1977 saw more than 200 theatre artistes converge at the one-time monastery, including dancers from India. For the first time in Italy, Oriental masters from India, Bali and Japan were seen on stage. “This meeting was a kind of a cultural shock for us because we were doing Western theatre and for the first time we understood that theatre could exist even without theatrical texts,” says Tiziana in an interview to CSP in Bangalore.

Since then, she and her fellow artists have been visiting India on a trot for 42 years, to learn different dance forms - Odissi, Bharatanatyam and Kathakali. “Of course there was a great fascination for what I can only call “the pure beauty” of Indian dance. But the real reason was that we needed techniques for actors which were absolutely absent in Europe. We wanted to start from the basics of theatre which lies in India in the Sanskrit text Natyashastra and in Sanskrit theatre,” adds Tiziana.

She says the transmission of craftsmanship in their culture is similar to the guru-shishya parampara of India. They have not learnt dance anywhere except India. Tiziana learns Odissi from her guru Aloka Panikar in Delhi and three actors are learning Kathakali in Kerala from a traditional guru.

Praveen has observed that they always work in a group. Everyone sits and discusses everything right from the conceptualisation stage. If Tiziana is performing Odissi, the Kathakali dancers are involved in some way. “Even if she is doing a solo, everybody is a part of it. They are aware of her journey and are a part of her learnings/teachings. I have been going there for the last six years, and I have seen that whoever comes here goes back and shares their learning of Indian dance with everyone.”

Every dancer is also a technician, a costume designer, puts away the chairs, sweeps, cleans, in short does everything. They quote the Natyashastra which mentions that all the process have to be experienced for it to be a complete art form.

Praveen says that when they do the costuming they study the details and go with the tradition and not on ‘what looks nice on me’. When they dance Kathakali, they do their own make up complete with the kajal with kobri enne (dried coconut oil).

TTB includes all kinds of theatre including street and open air theatre, not confined to conventional auditoriums. But the Indian dances are not confused in their performances. “The lines are separate but the basis of Indian theatre is strongly used in our dramaturgy,” says Tiziana.

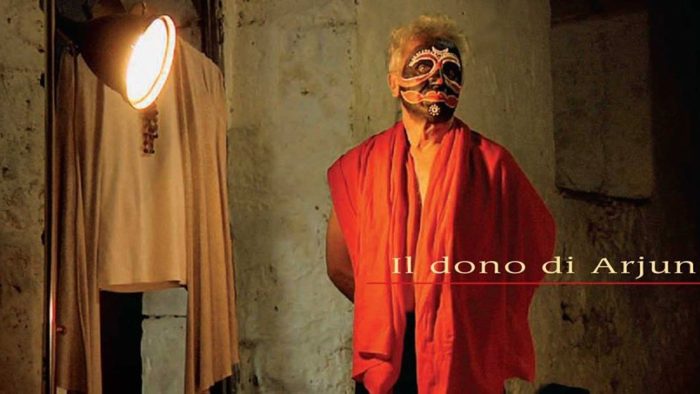

“On the tortoise shell” is a show whose title recalls the churning of the universe. This is a travelogue written by apparitions, sounds, drama and wonders. Characters and scenes from the East intertwine: a dancer performs a traditional Indian song. Other characters on stilts come up, from the deep end of the square. In this dimension where fables seem to be coming true, Kathakali performers dance with their famous wooden crowns with inlaid gold illuminated by flaming torches, while a shower of multi-coloured confetti settles on the scene and the public

When Praveen dances in Italy, audiences are told about the concept of the song being sung, and if it is an Ashtapadi they talk about Krishna, then about Jayadeva, and about the particular scene being performed - whether Radha is angry or flirting. “Because of the explanations, I can see that the audience is able to relate to what I am performing,” says Praveen.

TTB artistes perform in South America, Europe and are now moving to organising art activities. They have organised an all-night Kathakali performance in Budapest on May 25 as a part of Hungary’s traditional festival scene. Two of their artistes will be dancing with the Kalamandalam artistes. They joke that whenever they call their Italian colleague, he says he is busy, “reading the script” in Kerala.

It was as far back as 1545 that Italian scholar Sebastiano Serlio published his Trattato de architettura, a work that concentrated entirely on the practical stage of the early 16th century. One of the items in his treatise refers to the stage, where instead of the Roman acting platform, he introduced a raked platform, slanted upward towards the rear.

TTB has such a raked stage and when a troupe of Odissi dancers from India along with TTB artistes were doing a Pallavi, with the full orchestra playing, the dancers began to slide. Spinning the Bhramari, round and round, the dancers Indian and Italian, slid to the end of the stage. To calls for an encore.