“One of my pictures of divinity lies in the heart of a forest, where dense leaves are murmuring to the soil and waving to the winds, and the clouds are huddling up to hide, how fire of the sun moulds into water droplets, with a treepie bird on the right and a slithering snake on the left, and sambar deer, the prasadam lying in the front, the tiger is surrendering to the tigress as she embraces the earth and in the moments of one of the most impassioned courtships, there are no secrets; the whole forest must witness the godliness of a new forest in making,” writes Sudharshan Shaw, designer and artist, of his painting of a tiger.

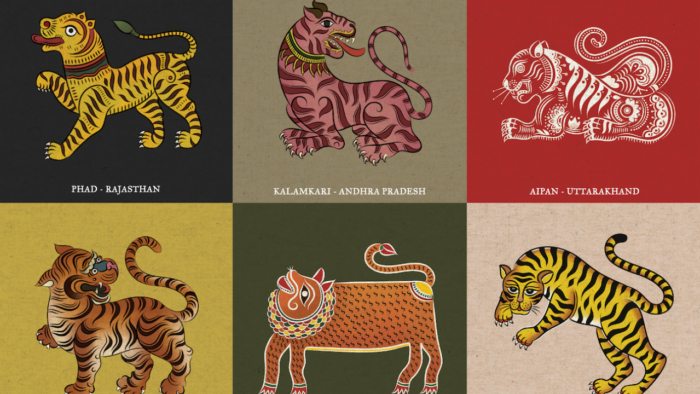

In conversation with CSP, Sudharshan says his mission is to create awareness of conservation through an Indic art lens. He is among a new crop of artists whose work is a visual menagerie, throbbing with life, at the juncture of nature and culture.

Originally from Orissa, Sudarshan says his inspiration comes from spending time in forests, villages and wild places. “I strongly believe that all species who have survived on earth for longer than us are much wiser and stronger in the truest sense. I like to forage for questions and wonder in the environment and then excavate historical documentations to look for all proposed answers quite often. And I like to share all these stories in a language that I am the most fluent at- the visual language called art, hence the union.”

His wildlife map of Odisha is inspired by the folk art of Pattachitra. The map says that Odisha is both the land of temples and tribes, and is a confluence of landscapes – forest to wetlands, waterfalls to lakes to mangroves, harbouring a wide range of flora and fauna. Home to the Olive Ridleys, Sudarshan’s map is compelling for its sheer beauty as well as for the dramatic information it presents. He says his representations of a few significant protected areas of Odisha – in Patachitra folk art, speaks for both the unique biodiversity of these wild spaces and the rich cultural heritage of the state.

He says when local art and everyday sciences come together, folk art is born. “This makes folk art a compelling communicator of complex sciences for common people. A stylized representation can serve accurate story-telling, its essence true to its land.”

His map of Andhra Pradesh, in a similar style, is inspired by the Kalamkari art of Srikalahasti in Chittoor. It is more extensive and goes beyond the scope of the Odisha map and includes the biodiversity, food and other elements of culture. While he does not claim to have learnt the art form traditionally, or completely, he says he hopes people will be curious about the various art forms on seeing his work.

Your art dives deep into the details...interpreting Indic culture and its values through the environment. Like in the Panchatantra, your creatures seem to have a thought process of their own. How do you express this artistically?

One of the most valuable Indic values is how all of us are small parts of one huge system. And the system is only as efficient as each and every life form who is a part of it. Our culture preaches cooperation over competition for survival. Animals have always been held in high regard, have symbolised divine prowess and inspired wonderful inventions and discoveries for ages. I believe I am fortunate to realise that the environment is an integral part of Indic practises and rituals. And I try my best to bring all of these into my art by representing the relationship of every organism I draw with their environment to start with. https://www.instagram.com/sudarshan_shaw/guide/my-picture-of-divinity_series/17842050671610150/

How do you intend to create an interest in India's vast and diverse art forms, by expanding their scope to include the primary caretakers of the environment - tribals?

India’s art forms are not just a representation of India’s diversity and vastness, these are resources that have the power to reshape a world that is going through a crisis of all sorts- from climate to leadership or health. A documentation of ancestral experiences, a storehouse of ancient wisdom and values, these artforms can connect us to the leaders of tomorrow - the tribals. Through Indian folk art, one of the most profound languages of these tribes, I am trying to make some space for crucial conversations and exchange of knowledge with them on a global level.

John Berger examines the evolution of our relationship with animals and how they went from muses for the very first human art, as cavemen and women adorned their stone walls with drawings of animals painted with animal blood, to spiritual deities to captive entertainment. In India too this has been the way we perceive the animal world. Do you think it has changed in modern times?

I think all of the above-mentioned kinds of relationships have existed and continue to exist simultaneously in India. There are tribes in remote corners of our country who still draw animals on their walls. They live in close proximity to wildlife and develop strong bonds with them. They revere them as wise ancestors, borrowing all of their ways of survival from the ways of the wild. There are communities in towns and cities who worship animals as associates of their human gods & goddesses and believe in serving them. There are sections of the society who, like some ancient kingdoms and empires, captivate and train animals for entertainment in various forms. There is definitely an emerging section who believe in becoming a ‘voice for the speechless animals’ and protect them. While the intent is thoroughly noble, it doesn't take away from the fact the approach comes from a place of superiority and mercifulness.

I have come to believe that only first-hand experiences in truly wild spaces can have mind-altering and humbling impact on us. And this is the reason why I feel tribes and communities who have lived in and around the forests for millions of years can best lead the conversations on our relationship with wildlife and conservation today.

Beasts of India and Waterlife are two books trying to create a narrative around nature and culture in the India context. What are the stories you are trying to tell through your work? Is the focus on relationships between man and nature or between art and science?

First of all thank you for introducing me to these brilliant works by Tara books. These are profound and inspiring indeed.

Through my work, I am trying to share my own explorations of wild spaces. I hope for people to understand relationships in general, how anything is related to everything and that there could be no such thing as individuality. I hope, together we all discover new ways and perspectives in natural systems, look up to the wild and embrace vastness and uncertainties without fear.

How does it feel when art is taken seriously, when scientists and Forest Departments asked you to join hands with them in conservation work? Is the message more powerful when expressed through art?

I am grateful to scientists and organisations who, unlike most institutions, strive to make science and law accessible to the masses in the first place. That is exactly when they would turn to art, a language that cuts across all kinds of limitations of other languages. The message is definitely simpler and much more inclusive when expressed through art.

What are the common threads in Indic art that you have used? How do regional differences come in visually?

Indic art has an inherent sense of community and a spirit of celebration. There is a rich culture of metaphorical interpretations. Geometry and details are sacred. I like to borrow all these for my artworks.

Indic art forms are very true to their motherland or their local environment and that is how diversity secures its expression. It feels like the strokes follow the wind and colours flow like the nearest river.

What is your message to the world about your work?

I hope that every painted canvas I share with the world, becomes a vast piece of wild land, that invites people to see the beauty in interconnectedness and oneness and how divinity lies in everyday wonder and magnificence.