Lahange S M, Vikash B, Bhangare A N, Shailza B. A Critical Review Study on Contribution of Ayurveda to Modern Surgery. Open Access J Surg. 2017; 6(3): 555693. DOI: 10.19080/OAJS.2017.06.555693.

Abstract

Anatomy is broadly appreciated as being one of the cornerstones of medical education especially for surgery. Learning anatomy through the dissected cadaver is viewed as the uniquely defining feature of medical courses. Explosion of knowledge in the field of surgery was feasible only due to exploration of human body through human cadaver dissection. Sages of ancient India are still relevant as they not only gave the vision of happy social and personal life, with great sense of ecological balance but they also discovered many scientific facts and truth about human body. Such discoveries formed the basis of many sciences of present era. In this topic we will discuss specifically about the facts of modern surgery which were already described in very scientific manner by the seers of Āyurveda. Suśruta is considered as the father of surgery even today, but if we go through the Āyurveda text, essentials of human anatomy are very precisely described by Suśruta, so Suśruta should also considered as the father of human anatomy. Ācārya Suśruta has paid great attention towards the structural organization of the human body. This was emphasized to such an extent that no surgeon should start his surgical carrier unless he is well aware with human anatomy.

Introduction

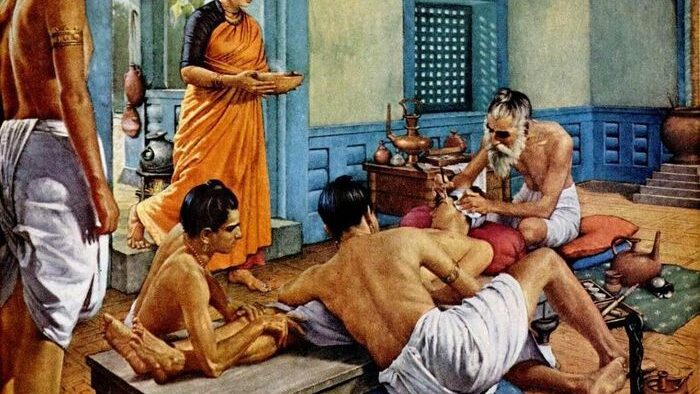

Ācārya Suśruta has not only mentioned the anatomical locations of various body structures but also given the detailed description right from development of various organs, intrauterine life of foetus, month wise development of foetus, nutrition of foetus, maternal health etc. Suśruta has separately explained the anatomical aspects of the body and one section of the Suśruta samhitā has been devoted exclusively for this, which is known as the Śārīr sthāna (section related to the study of human body). He planned to first deal with Sriṣtī utpattī kram, Embryology (Garbhāvakrānti Śārīr) and then anatomy of the human body. He also stressed on the importance of observational and practical experience in surgery. For this he mentioned a separate chapter named ‘Yogyā sūtrīya’ in Sūtra sthāna. He may be the first person to advocate dissection to gain the first hand knowledge of the human anatomy.

Suśruta was a strong supporter of human dissection as evident from his texts. His texts include a systematic method for the dissection of the human cadaver. They were mastered from extensive human dissection which they skilled despite religious interference. He considered that aspiring surgeons must first be an anatomist for skilful and successful practice. The physician or surgeon desiring to have the exact knowledge of Śalya śāstra should thoroughly examine all parts of dead body after its proper preservation. Practical knowledge along with theoretical knowledge is very essential for any practitioner. Although it is considered that Plastic Surgery is a relatively new branch of science but the origin of the plastic surgery had its roots more than 4000 years old in India, back to the Indus River Civilization.

The ślokās (hymns) associated with this civilization were compiled in Sanskrit language in the form of Vedas, the oldest sacred books of the Hindu religion. This era is referred to as the Vedic period in Indian history during which the four Vedas, namely the Rigveda, the Sāmaveda, the Yajurveda, and the Atharvaveda were compiled. All the four Vedas are in the form of ślokās (hymns), verses, incantations and rites in Sanskrit language. ‘Suśruta Samhitā’ is believed to be a part of Atharvaveda. Perhaps the greatest contribution of Suśruta was the operation of rhinoplasty. The detailed description of the rhinoplasty operation in the Suśruta samhita is incredibly meticulous and comprehensive. There is evidence to show that his success in this kind of surgery was very high. This need not come as a surprise because surgery (Śastrakarma) is one of the eight branches of Āyurveda, the ancient Indian system of medicine. The oldest treatise dealing with surgery is the Suśruta samhitā. Suśruta was one of the first to study the human anatomy. Suśruta moved by his intense human approach to life and equipped with superb surgical skills, did the operation of rhinoplasty with remarkable skill, grace and success. The details of the steps of this operation, as recorded in the Suśruta samhitā, are amazingly similar to the steps that are followed even today in such advanced plastic surgery. The famous Indian Rhinoplasty (reproduced in the October 1794 issue of the Gentleman’s Magazine of London) is a modification of the ancient Rhinoplasty described by Suśruta. Even today forehead flap is referred to as the Indian flap.

Suśruta took surgery in medieval India to admirable heights and that era was later regarded as the Golden Age of Surgery in ancient India. Because of his numerous seminal contributions to the science and art of surgery in India, he is regarded as the ‘Father of Indian Surgery’ and the ‘Father of Indian Plastic Surgery’. In “The source book of plastic surgery”, Frank McDowell aptly described Suśruta as follows: “Through all of Suśruta’s flowery language, incantations and irrelevancies, there shines the unmistakable picture of a great surgeon. He attacked disease and deformity definitively, with reasoned and logical methods.” Suśruta, the father of Indian surgery has described the scientific technique of Rhinoplasty and Lobuloplasty (repairing of severed nose and lobes of ear in his treatise of Suśruta samhitā). It is evidently true that the modern surgery throughout the world has got inspiration from the ancient surgery of Suśruta and it has been quoted by Hersberg of Germany that “Our entire knowledge of Plastic Surgery took a new turn when these surgical techniques of India became known to us”.

Acārya Caraka studied the anatomy of the human body and various organs. He gave 360 as the total number of bones, including teeth, present in the human body. He also described the numbers of muscles, joints etc. in the Human body. He considered heart to be a controlling centre. He explained that the heart is connected to the entire body through 10 main channels. He also claimed that any obstruction in the main channels led to a disease or deformity in the body. He also described about the concept of body cavity. The object of present study is to trace out the most significant and valuable hidden treasures of anatomy and surgery practiced in the past. Attempt has been also made out to investigate the valuable materials of immense importance pertaining to anatomical surgical literature available in Āyurvedic literature.

Suśruta had depth understanding about various procedures which represents the equivalent of modern techniques used in plastic and reconstructive techniques and thus implies a good knowledge of human facial anatomy. The writings of many great eminent scholars passed from ancient India to Arabians after the invasion by Alexander the Great. From them it passed on to Greeks and Romans. Hence ancient India deserves the credit of origin of modern medicine rather than to Greece and Arabia. The paradox still persists why the achievements of this ancient Indian legendary was not in limelight.

Various Surgical Procedures Mention In Ayurveda

Aṣṭavidha śastra karma (Surgical procedures) (Su. Sū.5/5)

The Śastra karma (surgical procedures) is of eight types. They are: Chedya, Bhedya, Lekhya, Vedhya, Eṣya, Āhārya, Visrāvya and Sīvya [1-4].

- Types of Sadhyovraṇa (Traumatic wound) (Su. Ci.2/8-10)

Ancient Ācāryās have classified the traumatic wound of innumerable shapes with respect to their features into six types broadly:

- a) Chinna

- b) Bhinna

- c) Viddha

- d) kṣata

- e) Piccita

- f) ghṛṣṭa.

Yogyā sūtrīya (Principles of experimental surgery) (Su.Sū.9/4)

- Experiments of Chedana: The different experiments of Chedana should be demonstrated on pumpkin-gourd, bottle gourd, water-melon, cucumber, Eravāruka and Karkāruka. Chedana in the superior as well as inferior directions should also be implemented upon these.

- Experiments of Bhedana: The experiments of Bhedana should be demonstrated on leather bag, urinary bladder of an animal and leathern bottle etc. full of water and slime.

- Experiments of Lekhana and Vedhana: The experiments of Lekhana should be demonstrated on a piece of skin which must be hairy and those of Vedhana on the vessels of dead animals and on the lotus stalks.

- Experiments of Eṣaṇa and Āharaṇa: The experiments of Eṣaṇa should be demonstrated on wood which must be eaten by moth, bamboos, reed tubes and mouth of a dried gourd; and those of Āharaṇa on jackfruit, Bimbī, the pulp of Bilva fruit and on the teeth of dead animals.

- Experiments of Visrāvaṇa and Sīvana: The procedure of Visrāvaṇa should be demonstrated on a piece of Śālmali wood coated with bees wax and Sīvana should be practised on the borders of fine, closely knitted cloths and on the borders of soft leather.

- Demonstration of Bandhana (bandaging): The procedure of bandaging should be demonstrated on different parts and subdivisions on the dummies made of cloth. Experiments of Agni and Kṣāra karma. The experiments of the use of Agni and Kṣāra should be demonstrated on soft muscle pieces. Plastic surgery of ear should be demonstrated on soft leather, muscle bellies and lotus stalks.

- Miscellaneous experiments: The experiments of applications of nozzles of enema apparatus and the wound irrigation should be demonstrated on the side hole of an earthen pot full of water and on the mouth of a gourd.

Karṇa bandha vidhi (Techniques of repairing the ear lobuloplasty) (Su.Sū.6/10)

There are fifteen techniques of the repair of the ear. They are as follows: Nemisandhānaka, utpalabhedyaka, vallūraka, āsaṅima, gaṅḍakarṇa, āhārya, nirvedhima, vyāyajima, kapāṭasandhika, ardhakapāṭasandhika, samkṣipta, hīnakarṅa, vallīkarṅa, yaṣṭikarṇa and Kākauṣṭhaka.

- Nemisandhānaka: Out of them the Nemi repair technique is indicated when both flaps of the divided ear are thick, wide and equal.

- Utpalabhedyaka: This technique is indicated when both flaps of the ear lobule are circular, wide and equal.

iii. Vallūraka: It is indicated when both flaps of the divided ear lobule are short, circular and equal.

- Āsaṅima: It is indicated when the inner fap of the divided ear lobule is long and the outer flap is almost negligible.

- Gaṅḍakarṇa: It is indicated when the outer flap of the divided ear lobule is long and the inner flap is almost negligible.

- Āhārya: His technique is indicated when both flaps of the divided ear lobule are absent.

vii. Nirvedhima: It is indicated when both flaps of the divided ear lobule are absent upto the root of the ear and it is repaired with the tragus as the base.

viii. Vyāyajima: This technique is indicated when one of the flaps of the divided ear lobule is thick, the other one is thin or one is regular and the other irregular.

- Kapāṭasandhika: It is indicated when the inner division is long and the outer one is short.

- : It is indicated when the outer division is long and the inner is short.

These above ten techniques of ear repair are curable. Their nomenclature is almost self-explanatory about pattern of the technique involved. The five techniques beginning with Samkṣipta etc. are not curable.

- Samkṣipta: It is indicated when the pinna is atrophied and one flap of the divided ear lobule is absent and the other one is very small.

- Hīnakarṇa: It is indicated when both flaps of the split ear lobule are devoid of a base and little musculature is present in and around the cheek.

iii. Vallīkarṇa: It is indicated when the ear lobule flaps are thin, unequal and short.

- Yaṣṭikarṇa: It is indicated when both flaps of the split lobule have keloids, are avascular and very small.

- Kākauṣṭhaka - It is indicated when the flaps of the split ear are devoid of musculature, have abridged ends and an insignificant blood supply.

Nāsikā sandhān vidhi (Rhinoplasty) (Su.Sū.16/27-31)

Suśruta describes the proper method of rhinoplasty when the nose has been cut off. Taking a tree leaf which must be of size similar to nose and placing it on the cheek, a flap should be raised of the same size from the side if the cheek maintaining its continuity; it should then be approximated to the front part of the nose after making the nose raw and then the surgeon should quickly suture the same by the correct technique. Having examined the nose which has been properly sutured and correctly shaped, the same should be fixed by two tubes and elevated. Then, the powder of Rakta candana, Madhūka and Rasāñjana should be sprinkled on the nose after elevating it. It should be dressed properly with cotton and should be soaked repeatedly with sesamum oil; Ghṛta should be administered to the patient after the previous meal has been properly digested and a purgative should be prescribed as instructed. When the graft has properly taken up, base of the same should be snapped. The short graft should be elongated and the long graft should be made uniform.

Auṣṭha sandhān vidhi (Su.Sū.16/32)

Plastic surgery of the cleft lip should be done similar to that of rhinoplasty but without the use of two tubes. Only he who knows these techniques, is entitles to be the royal physician.

Types of Sīvana karma (Suturing)(Su.Sū.25/22)

The edges of the wound should be sutured by Gophaṇikā, Tunnasevanī, and Ṛjugranthi and by other techniques of sutures as and where applicable [1-8].

Cikitsā of Baddhagudodara (Intestinal obstruction) and Parisrāvyuodara (Intestinal perforation) (Su. Ci.14/17)

Cases of Baddhagudodara (intestinal obstruction) and of Parisrāvyuodara (intestinal perforation) should be oleated, fomented and anointed and then their abdomen should be incised below the naval, four Aṅgula (Fingers) beyond the midline on the left side, and after bringing out the intestines four fingers in length at a time, they should be inspected and the stones, hair balls or faecoliths obstructing the intestines should be removed. After applying Madhu and Ghṛta the intestines should then be put back in their original position and the external abdominal wound should be sutured. Similarly in case of Parisrāvyuodara (perforation), after removing the foreign body and cleansing discharges, the edges of the hole in the intestine have been brought together should be got bitten by black ants. When the ants have bitten the intestines their body should be chopped off leaving the heads behind. Then suturing should be done as before and other reparative measures should be taken as described earlier. Black clay mixed with Madhuka should then be pasted and bandaging done. Thereafter, keeping the patient in a room without wind, further post operative instruction should be issued; he should be kept in a trough full of oil or Ghṛta and a diet of milk should be given.

Cikitsā of Dakodara (Ascites) (Su.Ci.14/18)

A patient of Dakodara (ascites) should first of all be managed with the Vāta alleviating oils and subjected to sudation therapy with warm water. He should sit and held firmly in the armpits by dependable persons surrounding him. A deep puncture as deep as a thumb breadth should be made by a trocar below the navel, four Aṅgula beyond midline on the left side. Then, a tubular instrument made of tin or of any similar metal or of quills and open at both ends should be introduced and the ascitic fluid should be removed. Thereafter, the canula should be removed, the wound anointed with oil and salt and then bandaged. All ascitic fluid should not be removed in one day. If removed all at once, it causes thirst, fever, body ache, diarrhoea, asthma, cough and a burning sensation in the foot; and the abdomen fills up again quickly in patients with lowered vitality [7-9].

Therefore, the ascitic fluid should be drained little by little at intervals of three, four, five, six, eight, ten, twelve or sixteen days. After the Doṣa (ascitic fluid) has been drained, firm bandaging by sheep’s wool, silk or leather should be done over the abdomen, so that gases may not cause distension. For six months the food should be taken with milk or Māmsa rasa of wild animals. Then for the next three months food should be given with milk, diluted with an equal quantity of water or with citrus fruit juices or with the meat juices of wild animals. For the remaining three months light and wholesome food should be taken. Thus in a year the patient gets free from the disease.

Cikitsā of the Mūḍha garbha (Mal presenting foetus) (Su.Ci.15/9), (Su.Ci.15/3)

The procedure of bringing out a mal presenting foetus is difficult than any other procedure. In this condition the procedures have to be carried out only by palpation (bimanual pressure) between the vagina and the liver, spleen, intestinal canal as well as the uterus. Pushing up or pulling down of the foetus, version, cutting up, incision, excision, pressure, straightening and tearing of the foetus have to be carried out by one hand only, avoiding injury to the pregnant woman and to the foetus. Therefore, after due permission from the king, all procedure should be carried out with the utmost care. The medicines should also be given. In case the foetus is dead, the pregnant woman should lie in supine position with her thighs flexed and her waist raised by a pad of clothes. Then the hand of the surgeon lubricated with the latex of Dhanvana, nagavṛttikā, śālmalī, clay and Ghṛta should be introduced into the vagina and the foetus should be manipulated. In case of presentation of legs, the foetus should be pulled downwards by its legs.

In case only one leg is presenting, the other leg should also be extended and delivered. In case of breech presentation, the hips should be pushed up along with the foetus and it should be delivered by extending the legs. In transverse presentation where the foetus is lying across like a transverse iron bar used for closing the door, the lower posterior half of the foetus should be pushed up and the upper half should be brought down straight into the delivery passage and delivered. In case of the head being bent to one side, the shoulders should be pressed and pushed upwards, and delivery of the head is completed by bringing it down in the parturient passage. When the arms are presenting, the shoulders should be pushed upwards and the foetus is delivered by pulling down the head along its normal course. The last two mal presentations are incurable; therefore when the above measures fail, surgery should be employed for them. Cutting of the dead foetus should be done by Maṇdalāgra śastra (circular knife) not by sharp pointed Vṛddhipatra śastra as it will hurt the mother.

Arś (Haemorrhoid) Cikitsā(Su.Ci.6/4)

According to Suśruta the patient suffering from piles should be oleated and sudated. Thereafter, the patient, who has been suffering from various types of pain due to Vāta, should take unctuous and warm food consisting mainly of liquids and less of cereals so that the pain may be relieved. The patient should then be made to sit in a covered and clean place in moderate climatic condition and on a flat plank or on a bed. The anus should be facing towards the sun with the patient in the supine position and the upper part of his body held in someone else’s lap. The waist should be raised a little by a bundle of cloth or a blanket under it. The neck and the legs should be firmly fixed by a strap of cloth and the patient is held firmly by assistants so that movements are not possible. Then his anus should be lubricated with Ghṛta and a well lubricated (rectal speculum) instrument should be inserted straight into the rectum along its passage little by little while the patient is straining.

After its insertion, the piles should be visualised (examined); thereafter the pile mass should be pressed by a probe, wiped with a cotton swab or a piece of cloth and caustic applied. As soon as the caustic has been applied, the opening of the instrument should be covered by the hand of the surgeon and he should wait until the counting of one hundred. Then after wiping, the caustic may be applied again, taking into consideration the strength of the caustic and severity of the disease. The applications of caustic should be stopped when the piles begin to acquire the colour of the ripen Jambū fruit and get depressed and shrunken. The caustics should then be washed away by sour gruel, yoghurt, butter milk, vinegar or by the juice of citrus fruits. The pile mass should be mollified by the application of Ghṛta mixed with Madhuka and the instrument should be taken out. Thereafter the patient should be made to get up and sit in warm water, whereas cold water should be sprinkled over him [9,10].

According to some, warm water should be sprinkled. Then he should be taken into a room free from direct approach of wind and nursing instructions are given. The pile remnant may have to be cauterized again. Thus, the pile should be treated one by one at intervals of seven nights each. In case of multiple piles the right one should be managed first; after the right the left one and after that left posterior one; lastly the anterior ones should be treated. According to Acharya Vāgbhatta after being evacuated by taking enema, the person should sit either on a cot or plank. With the upper portion of the body placed a little high, the anus should face towards the sun, the region of the waist must be raised up, the thighs and neck restrained, by tying them with cloth and placed straight and held tight by attendants.

Aśmarī (Renal calculi) cikitsā (Su.Ci.7/30)

The patient should be oleated, when the Doṣās are eliminated and body weight reduced a little. He should be massaged with oil, sudated and given a feed; then, after finishing sacrificial offerings while the priests should chant auspicious Mantrās wishing welfare and after collecting all things mentioned in Agropaharaṇīya chapter he should be reassured.

- Positioning of the patient: Then the patient, who is strong enough and is not nervous, should sit down with the upper part of his body resting in the lap of another person sitting on a knee high plank facing east; the patient waist should be raised by cushions and his knees and elbows flexed and tied together by ropes or straps [11-13].

- Preoperative manipulation of the stone: Then, after massaging the left side of the well-oiled umbilical region, pressure should be applied by a fist below the naval until the stone comes down. The lubricated index and middle fingers, whose nails must be slimmed off then it, should be introduced

into the rectum and brought below the perineal raphe; thereafter, with manipulation and force the stones should be brought between the rectum and the penis. Keeping the bladder tense and distended so as to obliterate the folds, the stones should be pressed hard by fingers so that they become prominent like a tumour.

Management of Asthi bhagna (Su.Ci.3/18-19)

The surgeon should reduce all the movable and immovable dislocated joints of the body by the methods of reduction as traction, pressure, compression and bandaging [14].

Procedure of Arma chedana (Su.U.15/4-9)

The Arma thus irritated, should be fomented quickly and mobilized by the surgeon. The patient should then be asked to look laterally and the Arma should be lifted with the help of a hook at a point where it has become wrinkled. Then it should be held with a pair of forceps (Mucuṇḍi) or with the help of sutures and elevated without lifting it hurriedly. The lids should be held apart tightly because of the risk of being hurt by the instrument. The Arma thus weakened and suspended by the three instruments (viz. Hook, pair of forceps and anchor sutures), should be separated from all sides with the help of a sharp circular knife (Maṇḍalāgra). After it has been freed from all sides and also from the cornea and the sclera, it should be dissected as far as its attachment to the vicinity of the inner canthus where it should be excised, sparing the canthus carefully. If one fourth of the tissue at its attachment is left intact, there is no danger of injury to the eye. In case if there is any injury to the inner canthus, there will be haemorrhage or a sinus may be produced later on [15].

Cikitsā of Pakṣmakopa (Su.U.16/3-6)

Pakṣmakopa is a relievable disease of the lids. A person afflicted with it, should undergo oleation measures and be made to sit in a proper position. The skin of his eyelid should be excised obliquely in the shape and size of a barley-corn with the help of a sharp instrument, at a point two parts below the eye brow and one part away from the eye lashes, equidistant from the outer and the inner canthi. The surgeon should then carefully stitch the margins with horse’s hair. The part should be treated with Ghṛta and honey followed by the subsequent measures as described for wounds. One end of the stitch should be fixed by a bandage over the forehead and the other end should also be held there by the same bandage. When the surgeon has ascertained the scar of operated wound to have firmly united, he should remove the stitches of hair.

Cikitsā of linga nāśa (Su.U.17/57-60)

In neither too hot nor too cold weather, the patient should be subjected to oleation and sudation therapies. Then he should be made to sit and positioned properly after which he should be asked to fix his gaze towards his own nose continuously. Then the surgeon should hold a barley-shaped śalākā instrument between the thumb, middle finger and index finger of his right hand and should open the eyes and puncture the eyeball properly with confidence towards the temporal canthus avoiding two parts of the white part of eye from the cornea. The puncture should be made neither too high nor too low, nor at the sides and saving the network of veins. Then it should be directed towards the natural orifice. The surgeon should operate with his right hand on the left eye and with his left hand on the right eye.

Cikitsā of Lekhya Roga(Su.U.13/3-8)

Lekhana (Scraping) is mentioned in nine diseases of eye [15- 20]. Now it’s common technique is being given. The patient, after having oleation, emesis and purgating therapies, should be made to lie down supine in a room free from the sun and the wind, and held firmly in position by reliable persons. The lid should then be everted by holding it between the left thumb and a finger and fomentation applied to it with a pad of cloth dipped in lukewarm water. The lid should be kept carefully averted between the thumb and the finger by a piece of gauze so that it may neither move nor slip. It should then be swabbed with a piece of gauze, marked with a sharp instrument and finally scraped by it or by leaves. When bleeding ceases, fomentation should be done, and the lid should be rubbed with a fine powder of Manaḥśilā, trikaṭu, rasāñjana and Saindhava mixed with honey. The lid should then be washed with warm water, irrigated with Ghṛta and treated like a wound. Fomentation and Avapīḍa nasya should be applied from the third day onwards.

Discussion

All the eight types of surgical procedures mentioned in Āyurveda are practiced in modern science also. The first one is Chedana (excision) means complete removal of an organ; Bhedana (incision) usually refers to a cut made during surgery; Lekhana (scraping) means to remove from surface by forceful strokes of an edged or rough instrument; Vedhana (puncture) is a act of piercing or perforating with pointed instrument; Eṣaṇa (probing) means a slender, flexible surgical instrument used to explore a wound or body cavity; Āharaṇa (extraction) means to draw out or to pull out; Visrāvaṇa (draining) means to remove liquid from cavity by letting it flow away or out and Sīvana (suturing) is used for the purpose of wound healing. All these technique are not new but are known procedures since ancient era [20-23].

The concept of practical training mentioned in Yogyā sūtrīya adhyāya of Śārīr sthāna of Suśruta is still relevant. This is followed by the modern medical practitioners by performing the procedures of surgery like excision, incision, scraping, puncturing, probing etc. on dummies and natural objects which are having the same features. Before entering in the field of practice, the training at internship serves the same purpose which was proposed by Suśruta many years back. Basically this was the concept of anatomical workshops to enhance the surgical skills of surgeons. Even today such teaching methodology is followed by prominent medical institutes in the world. The necessary tool for performing any sort of reconstructive surgery specially related to face the profound knowledge of anatomy and dimensions of that specific part is must for a surgeon.

Suśruta has mentioned the procedure of Nāsika sandhān, karṇa sandhān and auśtha sandhān. Here he had not mentioned clear anatomy of nose, ear and lips but in Sutra sthāna where he described Pramāṇa śārīr, he described various Pramāṇa of these organs which further helps in doing sandhān (reconstructive procedures) [24-27]. Those are-Nāsāputa of two Aṅgula, breadth of Nāsāputa is one Aṅgula. By this description we can consider that Suśruta was known about the anatomy of these organs because without pursuing the knowledge of anatomy and dimensions, one cannot perform any surgery. In modern science, for medico-legal purpose, injuries caused by mechanical violence are divided into bruises or contusions, abrasions, lacerated wounds, incised or slash wound, punctured or stab wound and perforating wound. Similarly, ancient clinicians have classified the Sadhyovraṇa (traumatic wound) in view of their features into six types broadly. In both these sciences similarities can be seen accordingly.

Conclusion

Suśruta was the first person who resorted to human dissection to understand the structures of the body in detail. By the unique method of scraping the body layer by layer he also noted the features of various structures and described them accurately. The concept and procedure of reconstructive surgery has been explained in classics as Karṇa bandha vidhi, nāsika sandhān vidhi and Auṣṭha sandhān vidhi. All the eight types of surgical procedures and suturing techniques mentioned in Āyurveda are practiced in modern science also. With advancement of time, science is expanding its wings in every field but basic principles remain always unchanged. That’s why modern science also follows all these ancient principles so the knowledge generally found in modern medical literature is nothing but the amendment of Āyurvedic knowledge or literature.

References

- Caraka samhitā English translation by Priyavrat Śarmā Cikitsā sthāna to Siddhi sthāna, Chaukhambhā orientalia, Vārānasi, 2.

- Caraka samhitā English translation by Priyavrat Śarmā Sūtra sthāna to Indriya sthāna, Chaukhambhā orientalia, Vārānasi, 1.

- (1996) Caraka samhitā with Vidyotīnī hindī commentary by Kāśīnāth Śāstri, Gorakhanātha Chaturvedī, Part-1&2, Published by Chaukhambhā Bhārati Academy Vārānasi, (22ndEdn.).

- Diagnostic consideration in ancient Indian surgery based on Nidāna sthāna of Suśruta samhitā part 3 by GD Singhal, LM Singh, KP Singh, Chaukhambhā surbhārati prakāśan, Vārānasi.

- (2011) Essential Orthopaediccs, by J Maheshwari, published by Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers, New Delhi, edition 3 revised, 7threprint.

- Fundamental and plastic surgery considerations in Ancient Indian surgery based on Suśruta samhitā part 1 by GD Singhal, SN Tripāthī, GN Chaturvedī, Chaukhambhā surbhārati prakāśan, Vārānasi.

- John V Basmajian, Charles E Slonecker Grants method of anatomy. (11thEdn.), Williams and Wilkins, US.

- Peter L Williams Gray’s Anatomy. (38th Edn.), Chairman editorial board, churchill Livingstone, British Library, London, UK.

- Chaurasia BD (2004) Human Anatomy. (4thEdn.), Satish Kumar Jain for CBS publications and distributors, Darya Ganj, New Delhi, India, 2.

- Human Anatomy. (3rdedn.), Macminns.

- Non operative considerations in Ancient Indian surgery based on Suśruta samhitā part 6 by GD Singhal, RH Śuklā, KP Singh, Chaukhambhā surbhārati prakāśan, Vārānasi.

- Ophthalmic and otorhinolaryngological considerations in ancient Indian surgery based on Uttar tantra of Suśruta samhitā part 8 by GD Singhal, KR Śarmā, Chaukhambhā surbhārati prakāśan, Vārānasi.

- Pāriṣādyam Śabdārth Śārīram, Pandit Dāmodar Śarmā Gaur (1964) (1stEdn.), Śri Baidyanāth Āyurveda Bhawan Pvt. Ltd, Calcutta, India.

- Diagnostic consideration in ancient Indian surgery based on Nidāna sthāna of Suśruta samhitā part 3 by GD Singhal, LM Singh, KP Singh, Chaukhambhā surbhārati prakāśan, Vārānasi.

- (2011) Essential Orthopaediccs, by J Maheshwari, published by Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers, New Delhi, 3rdedn revised, 7threprint.

- Fundamental and plastic surgery considerations in Ancient Indian surgery based on Suśruta samhitā part 1 by GD Singhal, SN Tripāthī, GN Chaturvedī, Chaukhambhā surbhārati prakāśan, Vārānasi.

- John V Basmajian, Charles E Slonecker Grants method of anatomy. (11thEdn.), Williams and Wilkins, US.

- Peter L Williams Gray’s Anatomy. (38thEdn.), churchill Livingstone, British Library, London, UK.

- (2004), Chaurasia BD Human Anatomy. (4thedn.), Satish Kumar Jain for CBS publications and distributors, Darya Ganj, New Delhi, 2.

- Human Anatomy. (3rdedn.), Macminns.

- Non operative considerations in Ancient Indian surgery based on Suśruta samhitā part 6 by GD Singhal, RH Śuklā, KP Singh, Chaukhambhā surbhārati prakāśan, Vārānasi.

- Ophthalmic and otorhinolaryngological considerations in ancient Indian surgery based on Uttar tantra of Suśruta samhitā part 8 by GD Singhal, KR Śarmā, Chaukhambhā surbhārati prakāśan, Vārānasi.

- (1964) Pāriṣādyam Śabdārth Śārīram, Pandit Dāmodar Śarmā Gaur (1stEdn.), Śri Baidyanāth Āyurveda Bhawan Pvt. Ltd, Calcutta, India.

- Suśruta Samhitā English translation by KR Śrīkantha MurthyŚārīr sthāna, Chaukhambhā orientalia, Vārānasi, 2.

- Suśruta Samhitā English translation by KR Śrikantha Murthy, Sutra sthāna, Nidāna sthāna, Chaukhambhā orientalia, Vārānasi, 1.

- Suśruta Samhitā English translation by KR Śrīkantha Murthy, Uttara sthāna, Chaukhambhā orientalia, Vārānasi, 3.

- (1995) Suśruta Samhitā of Suśruta with Āyurveda Tatva Sandipīkā hindī commentary by Kavirāja Ambikā Dutta Śāstri, Chaukhambhā Sanskrit Sansthān Vārānasi, Part 1-2 (9thEdn.).