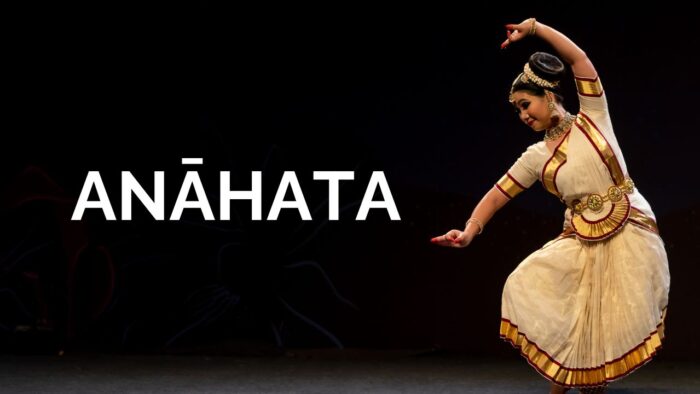

Malavika Menon a Mohiniyattam dancer talks of Anāhata as a state of being, a place of silence and liberation. Her project Anāhata – Seeking the Inner chord of Music delves into the different shades of bhakti. Drawing from compositions of some of the great bhakti saints, she will explore their expression through Mohiniyattam, bringing together different threads of bhakti from across India.

She says the project takes inspiration from the comment of poet and translator, A.K. Ramanujan - “A bhakta is not content to worship a God in word and ritual, nor is he content to grasp him in a theology; he needs to possess him and be possessed by him. He also needs to sing, to dance, to make poetry, painting, shrines, sculpture; to embody him in every possible way.” Says Malavika, “The bhakti saints had the most unconventional relationships of utmost intimacy, where every tone of rebuke, rage, humor, love, desperation was permissible. God was sacred, divine and beautiful, but he was also family!”

The poets whose work will be featured are Annamacharya, Akka Mahadevi, Nammalvar, Kabir, Marathi saint poets, Sree Narayana Guru, Lal Ded and Jayadeva.

Malavika is a Mohiniyattam dancer, choreographer and teacher, who has been learning and practicing the artform for over 18 years. She is a senior disciple of Guru Vinitha Nedungadi, who is one of the foremost practitioners of Mohiniyattam, from Palakkad, Kerala.

Malavika has been an active solo performer in this dance form and has performed at several notable art festivals in the country. She is also known for her work - Lāsya Mukharika, which was an endeavor to document the history, growth and development of Mohiniyattam through a series of interviews with more than twenty senior practitioners of the artform as well as some senior dance critics who have witnessed the evolution of Mohiniyattam from its early stages. This was an attempt to develop and archive informative material for the usage of dance students, researchers and art enthusiasts.

Do you find that Mohiniyattam has inherent qualities that make it suitable to show the ecstasy of bhakti? How is the expression different from say other Indian dances?

All Indian classical dances are stylised forms of art that have a nature of its own. Mohiniyattam’s inherent quality is the unhurried nature and slow paced movements that are filled with lāsya, or graceful lyrical movements. Bhakti comes in different forms, but the underlying emotion is the same across all regions of the world, irrespective of any language, region etc. Bhakti being a universal emotion definitely finds an important space in any classical artform. Dance is an offering in itself to a divine energy, and the aspect of bhakti is deeply rooted in all Indian classical artforms.

What drew you to Mohiniyattam once you had entered the world of dance? Were there other dance forms you practised before?

I began learning dance with Bharatanatyam at the age four and continued learning the art form for more than 12 years. I stepped into the world of Mohiniyattam at 6 years of age, after completing a few years of practicing and learning Bharatanatyam.

As much as I liked and enjoyed performing both dance forms, at some point in my dance journey I decided to focus on one artform and go ahead to involve myself more deeply in its practice, performance and research. It was at the age of 16 that I decided to focus completely on Mohiniyattam. It would have been the richness of the form in both abhinaya and nritta, combined with a strong movement vocabulary that I received training in that got me closer to this artform. My body started responding to the music and essence of this form very organically, and naturally the transition into Mohiniyattam happened. My Guru in dance also happens to be a Mohiniyattam dancer, which also resulted in me being inspired to take up learning and practicing this artform further.

In your series Lāsya Mukharika, you documented the evolution of Mohiniyattam through interviews. Do you feel that Mohiniyattam is underrepresented in the world of classical and semiclassical dance? What are some misconceptions about this dance form that you wish to remove?

Yes, at some point Mohiniyattam was underrepresented or did not come to the forefront as much as other forms like Bharatanatyam, Odissi or Kathak. Probably because it did not have enough practitioners and performers until the late 1990s and early 2000s. The concentration of good performers of Mohiniyattam was in Kerala and the artform did not have much representation outside of Kerala.

Some of the misconceptions about Mohiniyattam for a long period of time used to be that it is performed only by women, it is slow and boring, and involves mostly the rasas of sringara and bhakti only. But these misconceptions have been wiped out with the efforts of serious practitioners of Mohiniyattam who contributed greatly to widen the scope of performance in Mohiniyattam. It was a combined effort by two to three generations of dancers to introduce new themes, ideas, movement systems to this artform. Lāsya Mukharika was an attempt to document and archive this evolution of the artform by interviewing some of the most important Mohiniyattam artistes in the history of this artform and understanding their journeys with dance.

What gave you the idea to unite several cultures from different parts of India into this project? Do you feel the multilingual nature of the compositions will be better to show the true spirit of the bhakta?

I have been interested in reading bhakti poetry for a couple of years now. It was a sudden idea to incorporate a melange of bhakti poetry in a Mohiniyattam production. The concept arose from the thought of showcasing bhakti with not just a spiritual approach to the divine, but also by portraying the intimate and close relationships many bhaktas had with God. God became family, and was humanized by the poetry of many bhakti saints. I was interested to bring this aspect to light through this dance production. To convey this I wanted to pick and choose compositions of different bhakti saints coming from completely different backgrounds of region, language, class and caste, but their journey was very similar in many ways. The spirit of bhakti overflows in every composition, and the fact that it is multilingual only adds on to the idea that bhakti remains a constant in every life as is universal.

How do you intend to represent the universality of Bhakti while retaining each unique flavour of the regional poems, and Mohiniyattam itself?

The poems will be musically composed in a style that suits Mohiniyattam. However the language it will be sung in will be from the original text it was composed in. The language used will not change, the musicality and cadence of the lyrics will be understood so as to retain its regional flavour while composing the music.

These poets come from different parts of India and wrote in their regional languages, thus making this work multilingual. All the poetry will be visualized in the movement language of Mohiniyattam, which in itself is lyrical and has a special importance for poetry in its repertoire. Being the classical dance form of Kerala, the traditional compositions in Mohiniyattam are mostly in Malayalam and Sanskrit. However, poetry and other music compositions in Tamil, Telugu and Hindi have been adapted to Mohiniyattam previously as well.

This project has been envisioned as a solo production of Mohiniyattam, which would be 60 - 90 minutes in duration. The music will be specially composed for this work, and the studio recording of the same will be done so as to create an opportunity for repeated presentations. The work will be premiered as part of the Soorya Festival in Trivandrum, Kerala.

Would this also in some ways expand the Mohiniyattam repertoire from only Jayadeva's compositions to other compositions.

The concept of bringing together the works of multiple bhakti poets in one presentation would be a novel one as far as the Mohiniyattam repertoire is concerned. Traditionally, Jayadeva’s Ashtapadis are widely performed in Mohiniyattam, but the works of the other poets are not much tapped into, hence making this an interesting as well as an important production to work on. The unhurried and lyrical nature along with the importance of taking the essence in a poem and visualizing it in its movement language with the help of stylised abhinaya and nritta is at the core of this dance form’s vocabulary. The challenge lies in bringing together the different languages and tonality in each of the selected poems to give it an appropriate musical composition that will not take away from its regional flavour but at the same time suit the spirit of Mohiniyattam.

The poems of Lal Ded, Andal, Mirabai, Namdev, Akka Mahadevi are all rarely or almost never been adapted into the style of Mohiniyattam. While some other Indian classical forms have adapted this poetry, it would be a new attempt as far as Mohiniyattam is concerned.

How do you think we can achieve a state of Anahata through our dance forms. You quote AK Ramanujan in saying we need to possess our deity. Are the two linked?

Anāhata in this context refers to the state of mind that has found an inner peace and silence. The point of finding one’s inner music where all other noise is silenced. The true spirit of all classical dance forms is also to find this inner peace or vishrānthi where all other externalities become blurred and only the dance exists. In a way, a bhakta also seeks such a silence, where he/ she can become one with the paramātma. Where one’s body, mind and soul is tuned to attain mukti or sayoojya. The process or experience may be different, but dance is also a prayer that is done with one’s body, mind and soul to attain that oneness.

As AK Ramanujan refers to the bhakta’s state of possession, a dancer’s state of being completely immersed in the dance is also definitely similar in philosophy. Only with complete immersion, the true spirit and power of our classical dance forms can be experienced.

What new insights will music lovers get who have heard these timeless songs scores of times when they see your performance? How will the music be transformed?

The music for this production is being planned and composed in such a manner that it suits the rhythm of Mohiniyattam as a dance form. Having said that, it is also important to keep the spirit of these songs and the cadence and rhythm of the poetry intact. Some of the music compositions are timeless pieces that are very widely heard, but the newness will be the form in which it is danced to. A Marathi abhang is not something one gets to see in the Mohiniyattam dance style. So the challenge is to create choreography that merges with the music and will be a different and fresh visual treat for the audience.

Some verses such as poetry from a famous work of Sree Narayana Guru will be rendered in a Carnatic raga and given a new voice when added with a traditional pure dance piece such as the Cholkettu in Mohiniyattam. Some of the poetry that we may have heard as a bhajan or kirtan, when taken for dance will have its own flavour and form. This would certainly be a fresh experience for viewers.