Pepita Seth has been in Kerala for over four decades. She says that people like her - British, female, foreign, are “not supposed to enter Kerala’s temples and should not even dream of doing so at Guruvayur.” However, in 1981, she was allowed in officially and otherwise. A permission which she says changed her whole life.

When she was awarded the Padma Shri she was listed as Pepita Seth, Kerala. When she went to Guruvayur after the announcement of the award, a ritual artist told her that this was the first award for Guruvayurappan, and for someone from Guruvayur! “For them, it was like a member of the family getting the award. Not untrue, when I consider all those who have, over the decades, done so much to help me,” says Pepita.

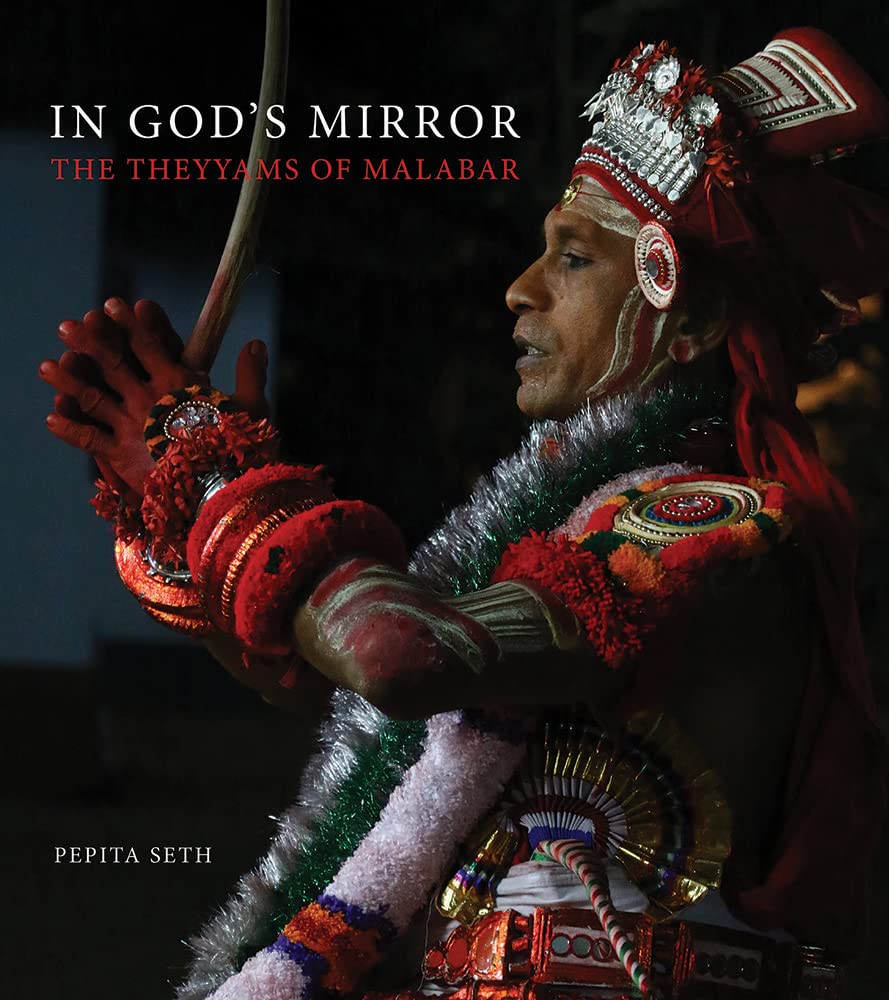

In this interview with CSP, Pepita talks about her second book - In God’s Mirror, The Theyyam Universe. See an ealier piece by her here: Theyyam - The Power to Call the Deities Down - Center for Soft Power (indica.in). Indica supported the publication of the book with a grant.

You have now published your second book. So how is working on In God’s Mirror, The Theyyam Universe different from Heaven on Earth: The Universe of Kerala's Guruvayur Temple in terms of documentation and experience?

While writing the book on Guruvayur, I had already worked on Theyyam and so I didn’t have to run around a lot this time. As a photographer, the main difference was that Guruvayur was in a contained space. My only problem was that one pooja looked exactly like another and so there was not going to be enough visual difference, but I learnt a lot from that experience. Theyyam is completely different, but you apply the same principles as when I started off as a film editor. I am now working on a series of costumes.

As soon as the Guruvayur book was released I went to Malabar to see the theyyakkarans - Lakshmanan Peruvannan and Murali Panikkar, their families, and other practitioners. Although they suggested that I continued working on Theyyam I refused, reasoning that I was now much older and no longer an innocent. I also knew, or thought I did, exactly how much stamina a long term commitment would demand. Yet since nobody took the slightest notice of my protestations, I sensed that my return was assumed. As a result I made a request: that the book would be a collaborative effort. What I never expected was their condition: that I stayed with them. It changed absolutely everything, giving me extraordinary access, taking me into their homes and being part of their lives. Furthermore, it meant that I saw how Theyyam impacts on their daily lives, what it actually means to ‘carry’ a deity, to be a practitioner and, above all, to hear their stories and catch some of the inner nuances. It took little time to realise I had wildly underestimated the stamina ultimately required. Yet as 15 years came and went, far exceeding the time I had expected to devote to Theyyam, I became tangibly aware of the role being played by Theyyam’s deities. My growing suspicions were clarified one morning when I approached Patamatakky Bhagavathi to make my offering and receive her blessings. After looking at me she took my hand, pulled me close and said: ‘You should never think it was your decision to do this work. It was not. It was our decision.’

Having worked in films, I was aware of different angles, close ups, longshots, big shots. I seldom photograph something from the same angle, unless I am boxed into it, which sometimes happens. The first time I covered any kind of ritual in Kerala was the initiation of a Velichappadu (oracles, or in Malayalam the Revealer of light). The temple was small, it was not only jam packed but it was also very clear who would sit where. I thought to myself that I couldn't shoot the same view the whole time, nor could I get up and move around, so I decided to do what I would have if I was shooting a movie. I took close ups of the priest’s hands with the flowers and things like that.

How do you know what is special? What is special both for the Indian seeing this day in and day out, and for the person who has not seen this at all? How do you capture something that is of interest for both of them?

The point of interest actually is not the deity. It is the man. The first part of the Theyyam performance known as Vellattam or Thottam is performed in a light manner without any elaborate costume. Here the man has really pale makeup, but you can see the face. The Thottam mudi (tuft) is very small. I thought to myself if this is what is going on the outside, what is going on on the inside. So of course I love the elaborate costumes and everything, but in a way I think the Thottam is really extraordinary because you see the disappearance of a human being.

You see a logic to the rituals, and there’s a 90 percent chance they will follow a pattern. If it was a new shrine, and if he’s moving the light this way, then that would be the best place to be. So I observe the set up of the shrine very carefully. Sometimes these happen in open fields and they would disappear for two hours.

After a time, and certainly after 15 years, I have a clear idea of what most deities that I saw would do. That did not mean that they always did it like that. They could go off the script as it were, but you get used to it and you also develop a sixth sense.

Two things you get a sixth sense about is knowing that they're not going to do what you think they're going to do and the second is which is the safest place to stand because they can move with tremendous speed. They are not bothered if you're standing right in front of them, they'll just roll right over you. The best and safest place to stand is right behind the chanda (cylindrical percussion instrument) players, because the one thing they're not going to do is crash into the chandas. The chanda players know exactly what is going to happen and they would do these little head movements. Sometimes I would run somewhere, not having a clue, but then there was this kind of backup which was fantastic.

All of Indian art is meant to elevate the audience to the same level of consciousness as the performer. So did you experience to some measure what he's experiencing?

Yes absolutely I couldn't and wouldn't do work on Theyyam if it wasn't affecting me. For me if the divine is in man, then, of course, when the divine is there there’s the man too, I suppose.

When I first went to Malabar, people told me I was wasting my time. They would say, ‘They will take the shirt off your back, they will bleach you white, they will not cooperate.’ Well, I finally came to the conclusion that there was something wrong with the people who made those statements because it's not true. At the same time, the Theyyam people do have very clear ways of literally tripping people up and you can see it coming. When they wear the big head dresses they know within a millimeter what the available space is, they really do. But I have seen people being knocked over by it. And then the chanda people will look and start laughing which means he had it coming.

How is it different from the Guruvayur experience, where you actually have the deity in front of you? Is there a difference between how you experience the divine?

Well, in a sort of way, no. It's the same but different in Theyyam, which is the multiplicity of it. I spent an entire day with Lakshmanan and, one day, trying to find out exactly who Chamundi was as there are several theories. I asked him whether she was Annapurneshwari’s daughter or her sister. At the end of the day, he said, ‘I can’t give you a very clear answer. It all depends’. And really it does depend, you see what you want in the deity and I suppose the deity goes about its own routine. Visually and on some level it's completely different from Guruvayur, they couldn't be more poles apart but at the same time it's being driven by the same kind of power.

You have interacted with many scholars and practitioners. How do they all come together through your work? You have Lakshmanan on one hand and the Namboodiris on the other. Where do their worlds meet?

There was an occasion when Lakshmanan and some other people were discussing who is a Kshetrapalan. I don’t think anyone actually knew but there were various theories about how a Kshetrapalan is and what does the word mean -is he the guardian of the temples, the guardian of the land or something else. Lakshmanan is very knowledgeable and he said ‘What we need is a Brahmin’. Now, considering their caste difference, that was a very strange remark. I asked him is that really who you need. He replied, yes, but it has to be somebody who knows what he's talking about.

So I rang up Narayanan Chittor Namboodiripad, who I had known since 1984 when he was conducting a ritual in Trichur. At that time, he had called me and told me I should go to his house to learn more about the rituals for my book on Gurvayur. I used to go every Monday to his house and he would teach me about the rituals, the poojas and the best part was when he said one day, and ‘now we are going to talk about the nature of God’. That was incredible.

The thing is those people don't fudge it because they know, so they don't have to. I fudge things because I don't know, but they are so clear when they speak. Anyway, I said to Thirumeni (he already knew that I was working on this second book on Theyyam and had heard me talking about Lakshmanan) that I would hand over the phone to Lakshmanan. They spoke for more than an hour. I had to keep running and charging the phone and finally when it was all over Lakshman turned to me and said, ‘I have to meet him’. So we visited Thirumeni’s ancestral home. It was strange. Thirumeni sat on one side, Lakshmanan on the other and I was in the middle. They were both kind of leaning forward. They got on very well and though Thirumeni had said he could speak for only two hours as he wasn’t well, it was about three and a half when we left. The next day when I called Thirumeni, he said ‘that man knows what I know’.

Their apparent differences were extraordinary. Thirumeni was a Namboodiripad, not just an ordinary Namboodiri. He was frail and just short of 80 years and Lakshmanan must have turned 50. So you couldn't see where they connected, but it worked so well that Lakshmanan used to come down by himself to speak to Thirumeni and those conversations must have been incredible because actually they were equals. One day Thirumeni rang me up and said, like a child, that he had always wanted to hear one of the Thottam songs and Lakshmanan had rendered it.

(Narayanan Chittoor Namboodiripad belongs to the ancient family of Chittoor Mana who were the spiritual advisors to different rulers in the South Indian state of Kerala including the Zamorin of Calicut. Son of Sankaran Namboodiripad, the Yajurveda exponent and Uma Antharjanam, Namboodiripad is the descendant of Vasudevan Namboodiripad.)

You are very much part of their social milieu. In very traditional settings how did you fit in as it is generally male dominated as it is in Theyyam?

Yes, that is true, but it is a little more fluid with the Theyyam people as there are some very powerful women around here. Often, the men have a better view point than the women. But if you go to where the Theyyam stands, that is the best. They know that you know how you're supposed to behave so therefore you can stand there. I know how to behave in their world. So it's okay. Murali, a youngster, was very fond of me and would rush up and grab my hand and say ‘Amma Amma’.

What has this experience taught you about identities both in society as well as in the world of rituals?

Most societies have rules and it's an automatic thing to make things work or not work. Sometimes I don’t have a clue as to who I am. In Malabar, women can get away with anything if they are determined. It is as if they have a shakti.

There is one Theyyam artist Santosh Peruvanan and I've known him since he was 12 when his father had died. As there was no one to train him, he went to Lakshmanan and asked him if he would. I'm really very fond of Santosh because he's really done so much without the normal sort of family backup.

One day there was a deity performance under a big tree during Panguni. They draw a shape and you have to make sure you stand behind it. Suddenly someone came from the shrine to Santhosh and asked rudely - should she be here? So Santosh pointed over to the shrine and said, do you see that Amma and do you see this Amma (pointing to me)? They are the same Amma and don't ever question what she does because she knows exactly where she can stand, far better than people like you.”

What was your research prior to your interactions with them? How much of your knowledge was from living with them and how much from books?

I've looked at stuff about Theyyam to know that I don't trust those books. That is not to say they're full of mistakes, but it's the same with the Guruvayur book. There's no list of books consulted or anything and people used to get very upset about this. But I haven’t quoted a thing because I had access to the people in the temple who knew. So why did I need to go and ask somebody who actually performed absolutely no role in the temple. I used to buy cheap books on Theyyam and I just stopped because I see now that if you don't have access to their lives or you don't know who they are it’s like going to a ballet and never talking to any of the dancers.

The luckiest thing that happened to me was the three months when Lakshmanan was making costumes. I didn't even have to get out of bed because, in the main room there was a bed and that's where I slept. I was just part of their lives.

You also talk about intuition and you say you always operate from a point where you do things based on gut feeling. So how did this workout for your two books?

I go by instinct. I don't know how that works and you can't question it. There was a wonderful man called Gurunathan who died five years ago. He doesn’t suffer fools, but he’s actually very kind. He asked me what I wanted to know and I told him Annapoorneshwari. Then he told me he had rights in the Annapoorneshwari shrine. He asked me to come to his house by 10 am and by that Sunday morning I had finished the chapter.

Also when I arrived in Malabar I went to the Chirakkal Kovilakam and met the royal family. Someone had given me the address of Ravi Varma and I didn’t realise that he was Royalty. So I went and met Thampuran and asked him the full story of the Bhagavathi. He asked me to come and stay with them and witness the festival when it happened in January. It was October and he asked me to stay on. When the Kaliyattam came up, he took me to the shrine and introduced me to everybody and left. Gurunathan told me a good 20 something years later, that when I had turned up, they knew.

There is a belief that when you want to know about Theyyam, you have to first see the Chirakkal Thampuran (royal) who takes you to a top performer, in this case Lakshmanan Peruvanan who would bring them to Gurunathan. I asked Gurunathan, ‘You've known all this time, but you never said anything’. He said they knew I was the right person to do this work, but at that time I knew absolutely nothing about Theyyam, so they thought they should let me get on with learning about it.

Can you tell us more about your love for elephants?

I used to have an elephant which actually belonged to my father and there used to be a variety of ink in the UK called Quink. So this elephant was called Quink. That is how I became interested in elephants. The first journey of India was to retrace my great grandfather's march from Calcutta to Lucknow in 1857 but I was obsessed with actually going to see elephants, which is what got me to Kerala.

How do you understand their role in temples today?

I remember the first day I went to Guruvayur, I was taken to where the elephants were. There were very few elephants and they were kept very near the temple. They told me not to go close. There was a beautiful elephant there but there were tears running down his face. Apparently all these elephants have three people with them and one of them, not the top guy but the second guy, was hitting him. The elephants were taken for a bath daily and they had chains but they were not attached to anything.

One day this cruel man came past the elephant, and it lunged at him. At exactly the same point, the good man crossed and the elephant got the wrong man. The problem was that they could not get the body, because the elephant was crying and waving its ears. Nowadays, everything has changed in Guruvayur. The main people are Government servants whose way of dealing with an elephant is hitting it. In the old days when I first came to Kerala I saw them wandering around people. Now they're chained when they go around the temple.

Do you think that any of these traditions and influences are at risk of dying due to lack of either interest or support?

Well, the answer is yes. When I first saw Theyyam in the 1980s, people said it would last for a maximum of 10 years. Now it is changing and there are young theyyakaras who don't know how to make the costumes and other things. The shrine people want to do everything fast and go home. One of the chapters deals with how the deity got furious with the shrine people telling them, “If you want me to hurry, why do you want me at all.”

Things are changing due to the market forces. The government is really pushing Theyyam for tourists, but Theyyams are not for tourists and it is not a performing art. I'm not saying it doesn't have elements of performance in it. It is a ritual just like going and standing in front of Guruvayurappan. In Theyyam, you have aged people prostrating at times before a 10 year old.

There are some amazing stories. Once a woman came up to the Theyyam, weeping because her husband was an alcoholic. He beat up children, there was no food on the table and everything was in a terrible state. The thing is that Theyyakaran was her husband. She was trying to get help from the Theyyam who gave it to her.