Ptahmassu K.M. Nofra-Uaa is an internationally noted iconographer whose celebrated work has been featured in publications including best-selling author Nicki Scully's book Sekhmet: Transformation in the Belly of the Goddess. He is the founder of Icons of Kemet, dedicated to the crafting of unique God-images for use in worship of the ancient Gods of Egypt. A spokesperson for devotional polytheism, his poetic hymns have been published by Neos Alexandria/Bibliotheca Alexandrina. He is a priest of the Temple of Isis California, a legally recognized sanctuary of the Goddess Isis in the United States, and a Priest-Hierophant in the international Fellowship of Isis, whose aims include the celebration of the Egyptian Goddess Isis and related Goddess traditions from around the world. (Official websitewww.iconsofkmt.com, Official store www.store.iconsofkmt.com)

Center for Soft Power is privileged and grateful for this Interview with Master Iconographer Ptahmassu K.M. Nofra-Uaa

You say you have experienced the power of Kali ma and that you had a book of Sri Ramakrishna Paramhansa which helped you in your life. How did they come into your life?

Ptahmassu Nofra-Uaa: I first encountered the Goddess Kāli as a boy in a book on the religions of India given to me by one of my teachers, and I admit I was hooked. There is something captivating about Ma, and Hers is the power to split open the most resistant of hearts, to conquer the most adamant ego, to open up wide the most closed of spaces. She finds your sadness and walks with you through those terrible places which the human mind creates, the illusion of material life and suffering as permanent phenomena; and She tears down those illusions, revealing that it is the spiritual life, the non-physical state, that is the Ultimate Reality, the highest goal possible. It is through this realization that human beings can strive for union with the Divine, which can be achieved through bhakti yoga, the profession of one who thirsts for the Divine above all things.

As a young man I came into some misfortune and became homeless for a number of months. Sometimes I was offered a temporary place to stay by friends or friends of friends, and survived primarily on handouts from kind people who frequented the coffee shops I spent my daylight hours in. At this time I was very devoted to my meditations and spiritual studies exclusively, and my days were spent reading the cache of books I carried around in my backpack. I went into a used bookstore one afternoon and was perusing the religious philosophy section when I came across The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna published by the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center. I sat down with it for over two hours, utterly captivated by the life of Sri Ramakrishna and His devotion to Ma Kāli, and finally decided to spend the last bit of money I had on the Gospel of Ramakrishna, instead of saving it for food.

Though I was at that time familiar enough with the philosophy of bhakti, something about the personality and message of Sri Ramakrishna touched me in a way no other guru or teaching had. I was in a certain amount of intense emotional pain at that time, a profound loneliness and depression, and also a fair amount of physical pain from an abscessed tooth, so I poured that pain and loneliness and depression into my relationship with Divine Mother, Whom The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna inspired me to reconnect with. The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna spoke to me of a human soul compelled by intense, painful longing for a true vision of Divine Mother, the Ultimate Reality of the Universe. It spoke to me of a soul attracted to the Source of its own beingness, the Goddess Who reveals Herself to the bhakta as Ma Kāli. When Ramakrishna describes His heart "...being squeezed like a wet towel" during His first vision of the Mother, I understood that this is what it means to love the Divine so completely, so authentically that one becomes immersed in the very object of one's devotion, until there is no division between subject and object. This was the love I found for Divine Mother at this time in my life when real love was a chimera to me. Love as lust, desire, and attachment was something I knew all too well, but what I really wanted was a love not rooted in the ephemeral, a love not attached to that which is destined to dissolve. This is the kind of love Divine Mother wakes us up to, and it is such a shocking phenomenon when it happens, it can only come from the being of a Goddess with a sword that cuts through all attachment woven through the ego.

One of the great gifts of Sanātana Dharma to the world is this path of bhakti, the principles of which can be found in and applied to other religious/ spiritual paths; that is, the path in which the devotee gives over their heart wholly to the Divine, and places the Divine at the center of all activities and goals. This is something I post about constantly on social media, because I think it exemplifies how we as devotees of our Gods can experience the presences of the Gods directly in all our life, not just in temple, shrine, or during special ritual times. I think it's easier to think about the Divine when one is in a sacred environment, surrounded by incense, flames, and in the presence of beautiful mūrtis or idols. But what about the rest of the time? What about our busy workaday lives that consume so much of our time and energy? How can we experience our Gods then?

The path of bhakti- and in particular bhakti yoga - bridges the gap between Sacred and profane, spiritual and material, in that the bhakta trains their mind to bring itself back to the Gods at the center no matter what the devotee is doing- household chores, stuck in traffic, taking care of the kids, running errands, grocery shopping in a crowded store, sitting in class during a lecture. When the Gods are recognized as being the Source of all activity, worldly or spiritual, and when the world is recognized as being composed of the spiritual, as a vehicle for it, in fact, then there is no separation between the human soul and the Divine. There is no differentiation between the Personality of the Divine and the human condition. We see that all our life is directly connected to our Gods, that the Divine is the root of all life and activity in the material world, that there is nothing that is not the Divine. This realization in us transforms our "mundane" experiences into opportunities for Divine engagement, whether or not we are in a sacred space such as a temple or stuck in traffic in the middle of a congested city center. If our mindfulness is present with the Divine, then our most mundane actions can be filled with the Sacred.

Top - The Shrine of the Household Gods in the iconographer's home, Below: The Shrine of the Household Gods in the iconographer's home

Top - The Shrine of the Household Gods in the iconographer's home, Below: The Shrine of the Household Gods in the iconographer's home

Indians pray to a pantheon of deities called devas. Are there similarities to Egyptian gods?

Ptahmassu Nofra-Uaa: There are definitely similarities between the devas of Sanātana Dharma and the goddesses and gods of Egypt. Firstly, one sees that iconographically the netjeru or Gods are visualized anthropomorphically, and that these forms remain consistent throughout Egyptian history. There are the cosmic Creators such as the God Ptah, Whose iconography in anthropomorphized form never changes over a period of four-thousand or more years. He is depicted with attributes that remain with Him- close-fitting skull cap, straight, squared beard, and hands protruding from form-fitting sheath carrying the ankh-djed-was (ankh=life+djed=stability+was=dominion) staff of creation. The God Ptah is always instantly recognizable because of His consistent iconography, which reminds one of Brahmā or Śiva, and in particular the triśūla-trident of Śiva representing His śakti-powers. The ankh-djed-was staff held by Ptah is a combination of three divine attributes associated almost exclusively with the God Ptah in His role of Creator of all life, material and spiritual. Likewise, the triśūla-trident of Śiva embodies His three powers of icçhā-will, kriyā-action, and jñāna-wisdom. Śiva's trident is so closely aligned with Him that the God's presence may be represented by the trident alone, just as the ankh-djed-was staff is recognizable as that instrument of Ptah's powers as Creator of the universe, Gods, and living creatures.

We find in taking a closer look at the forms of the devas that these correspond to the manner in which the Gods of Kemet- ancient Egypt- are depicted. Consider, for example, the bimorphic form assumed by Viṣṇu, Who transforms Himself into a boar in the Śiva Purāṇa, and of Gaṇeśa with His elephant head and plump, human child's body. Such combinations of human and animal are the well-known hallmark of the Egyptian netjeru, Who often appear in temple iconography as animal-headed and human-bodied. But we also have the strong presence of the vāhana-vehicle in the devas, which signify aspects of a deity's power, such as the lion of Durgā or bull of Śiva. The Kemetic- ancient Egyptian- netjeru have what are called uhemu, animal intermediaries like the Hap- or Apis- Bull of the God Ptah, and these animals are regarded as the living manifestations of a deity's sekhemu or powers. These animals or birds are believed to be the carriers of a deity's concentrated power, which becomes accessible to the material world through such a manifestation. Now, in the Kemetic tradition, the netjeru do not actually ride their uhemu as the devas ride Their vāhanas, but still, the Gods of Egypt are very closely tied to the manifold animal forms with which Their living powers are associated. In fact, the Kemetic Gods can also appear in completely zoomorphic guise, or be represented by the animal whose head They more often sport.

It is this reverence for the inherent sacredness - this inherent divinity- in the natural world that most closely ties the devas of Sanātana Dharma with the netjeru of Kemet. The Goddesses and Gods of Egypt demonstrate Their powers and qualities through the animal kingdom, and also in the plant kingdom, which exists prominently in the divine iconography of Sanātana Dharma. We also find the same type of iconographic determinations made in both cultures, such as the attitudes or postures/gestures of deities that act as identifying factors, specific regalia and weapons particular to both local and national deities that serves to embody how each deity's powers are demonstrated, and family units that form the core values presented in the sacred story cycles of each deity. In the Kemetic traditions, goddesses and gods are presented in tight-knit family groups often consisting of a male deity, his female consort, and a divine child or children, which become the specific focus of temple cultus. In Kemetic theology, for example, we have the divine family of the God Ausir (or Osiris), the Goddess Aset (or Isis), and Their son the God Heru (or Horus), Whose family tribulations and exploits became central to Egyptian religious thought and ritual. We might compare this with the family of Śiva Pārvatī, and Gaṇeśa.

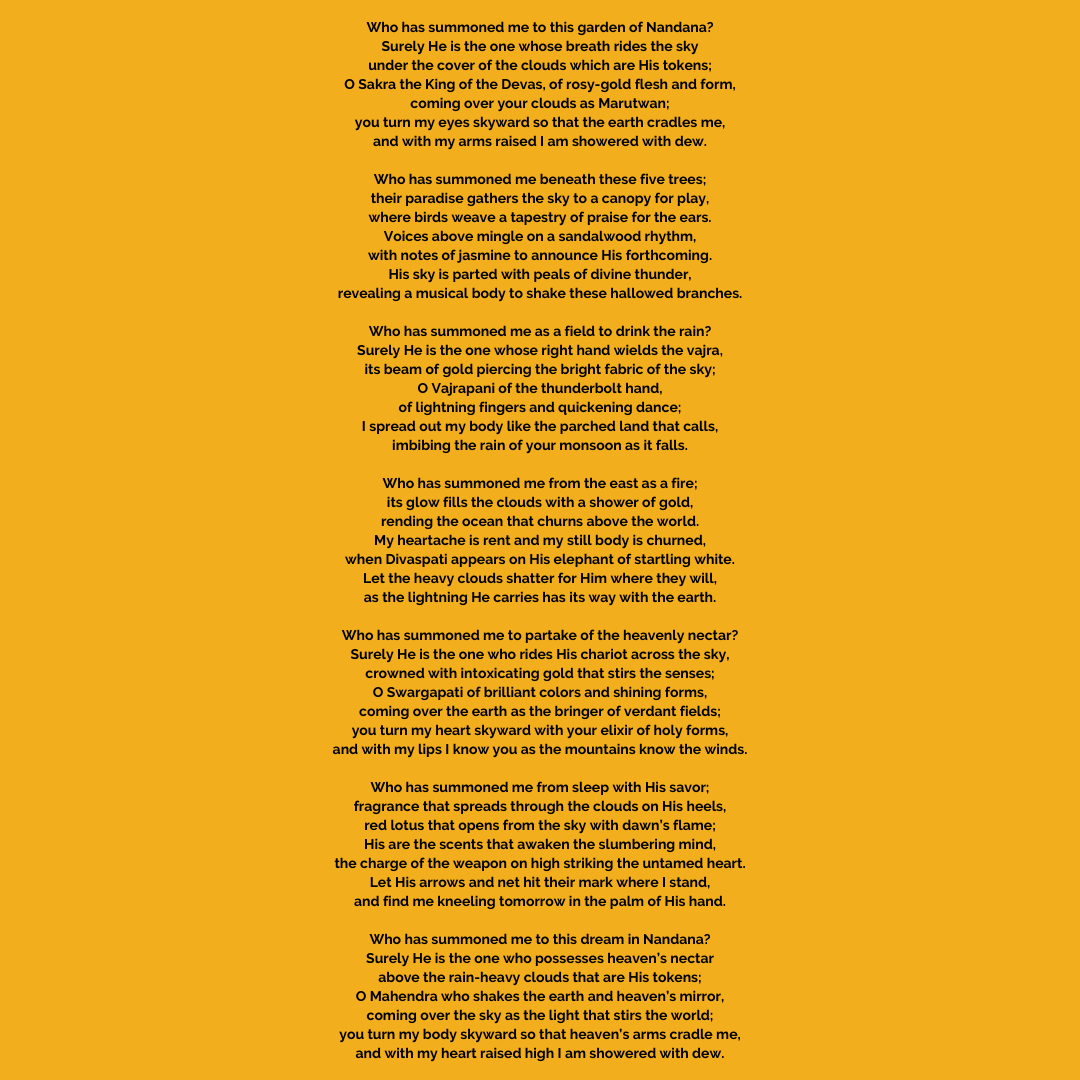

Goddess Kali watches over the iconographer in his studio

Lord Ganesha (middle) and Lord Indra (below)

You speak a lot about ancestral worship. Why do you think our ancient civilizations worshipped ancestors on par with the deities?

Ptahmassu Nofra-Uaa: Firstly, we recognize that our Ancestors have a vested interest in our success as human beings, that They want us to succeed in our endeavors, and that They understand what it means to live a human life fraught with all the difficulties and sufferings mortal life presents. Our immediate blood relations - those with whom we shared the closest familial ties while they were alive - are especially cognizant of the challenges we face on a day to day basis, and are more likely to lend us a compassionate ear once they have passed over into the spiritual world. Among these persons we might also choose to consider not only our blood relatives, but also very close friends who shared with us a deep spiritual connection. This would include peers in our religious communities, fellow devotees, teachers, gurus, satgurus, kulagurus, and āchāryas. We should understand that our karma has brought us into the presence of such persons, and that these ties will be passed down from lifetime to lifetime, meaning that they are also within our family of Ancestors and can be approached through prayer and devotion for the transmission of blessings.

In the Kemetic traditions we recognize the presences of the Akhu, "Shining Ones" or "Effective Spirits", Who embody all those Who have transmigrated the after death states and, because of Their virtuous deeds while alive, have received justification before the Gods and won a direct place in the domain of the Gods. While ones blood relations may be considered one's Akhu, it should be kept in mind that many Kemetics are non-Egyptians whose blood relations and family ancestors might be antagonistic to Kemetic beliefs, might be Christian, agnostic, atheist, or simply not on good terms with one, or for other reasons might not be responsive to the petitions of ancestor cultus. How does one maintain an ancestor practice under such conditions? Also, it is important to many Kemetics (practitioners of the ancient Egyptian religion) - who do not have blood ties to the native country of their faith - to establish spiritual ties with those who do, and the way in which this is achieved is through a sustained ancestor cultus to Egyptians who served the netjeru, that is, by petitioning those ancient Akhu or Blessed Dead with whom they feel a special connection. Kemetics who engage in this kind of Ancestor veneration often find themselves being "adopted" by ancient practitioners of their faith who are not related to them by blood, but become a source of spiritual strength and kinship nonetheless.

Why do our ancient traditions place such emphasis on Ancestor veneration? Because our Ancestors have already passed through the material world and entered the numinous spheres inhabited by the Gods, and it is through Their experiences that we too might gain insight and blessings from the Gods we share with Them. Our thread of connection with our Ancestors - be They Ancestors by blood or spiritual ties - is intimate due to our common humanity, our common emotions, needs, desires, and suffering of mortality. These are experiences our Ancestors understand from direct experience, including the affliction of mortality itself, which the eternal Gods, the devas and netjeru, do not share with us because Their state is numinous and not constricted by physical dissolution.

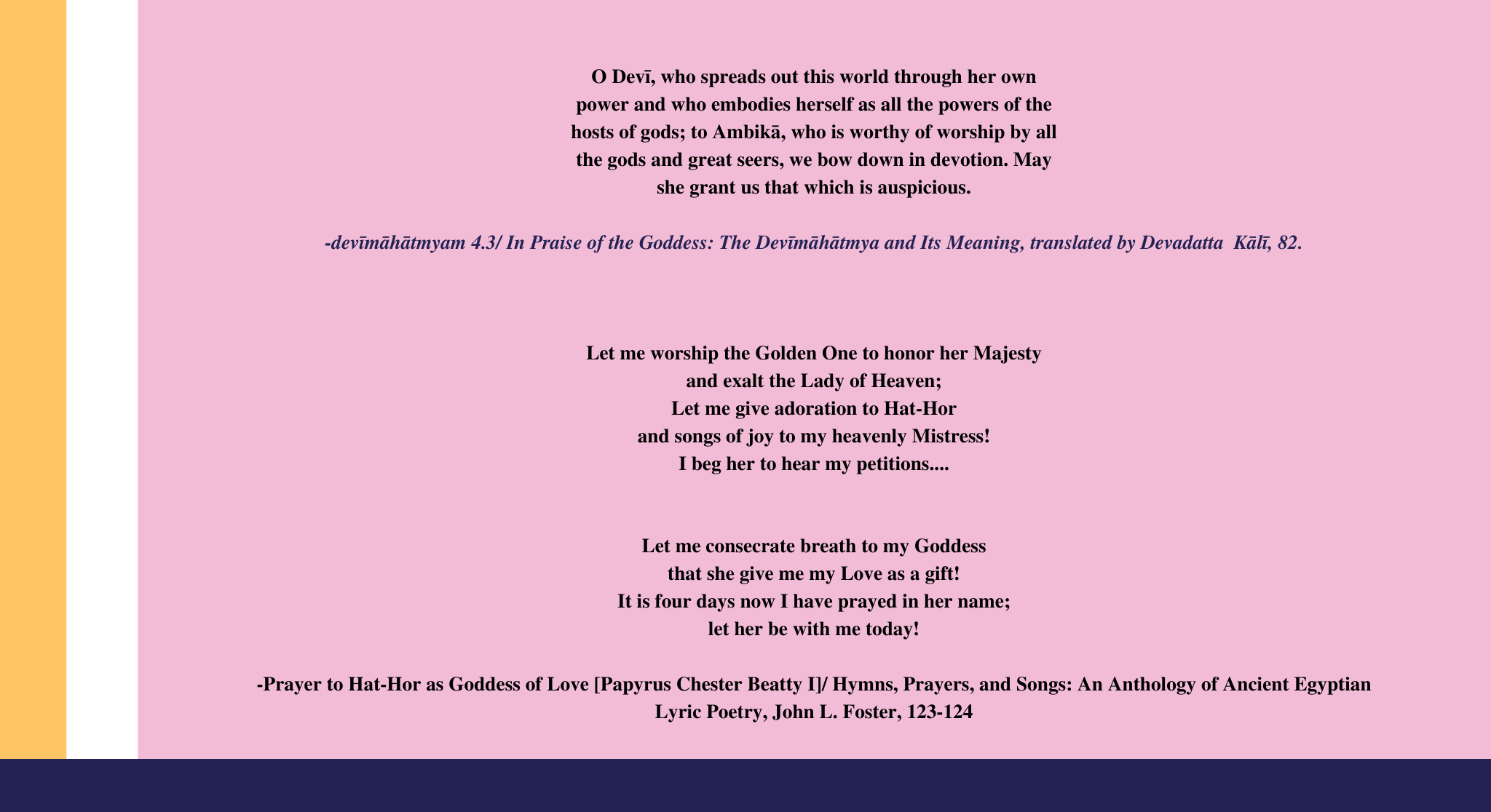

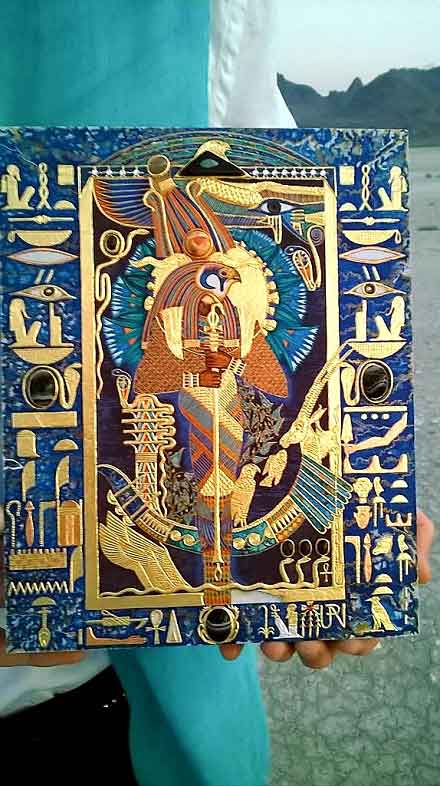

The Akem-Shield of Khnum-Ptah-Tatenen and the Egg of Creation

Have you been to India? Do you think our ways of worship are similar?

Ptahmassu Nofra-Uaa: I have never had the opportunity to make a pilgrimage to India, but this is something I yearn to do, for many reasons, the most important being that India is the oldest Dharmic civilization on our planet. She is the benchmark for how human beings can cultivate a direct relationship with the Divine and maintain that relationship without fail. The Sanātana Dharma of India gives us a more than 6,000-year-old record of what happens when human beings respond to the innate calling of the Divine, and develop their culture as a dialogue between the Gods and the human conscience.

As a devotional polytheist, my strongest inclinations are towards the actions that bring us into direct contact with our Gods, the active engagement of the Gods through the activities of prayer, worship, ritual, pilgrimage, meditation, the maintenance of cult images or idols, and the maintenance of sacred spaces such as shrines and offering places. I also live a tradition that has not had the fortune of being handed down in an unbroken chain since ancient times, as is the case with the Sanātana Dharma. Kemetics today have a difficult time in responding to the call of our ancient gods because we are not raised with an awareness of the authentic prayers, ritual forms, and modes of service native to the worship of our netjeru. We do not have an instantly accessible lineage of clergy or living temples to help us in the cultivation of our faith. These are all things Kemetics must uncover and study on their own, which means we need examples of how ancient polytheisms can be lived in the contemporary world.

This brings me to the answer to your question. Sanātana Dharma is in a unique position amongst the world's living belief systems in that it recognizes many Gods, devas or Mahādevas, thus its practitioners are raised with a strong sense of plurality in approaches to the Divine and in lifestyle choices rooted in these different approaches. It has maintained the same ritual forms for thousands of years, the same sacred architecture for temples, and the same sacred proportions and guidelines for mūrtis or Divine images. For devotional polytheists like me, striving to live a very ancient tradition rooted in the veneration of many gods, the milleniums-old practices of the Sanātana Dharma serve as living examples of how devotees today can engage the Gods through the maintenance of ancient ritual forms and modes of service. There are many layers of similarities one can detect between the sacred ideals and symbolism expressed in the worship of the devas of Sanātana Dharma and the netjeru of the Kemetic traditions.

One significant aspect that has thankfully remained from the ancient Egyptian religion is its temple record concerning the highly specialized ritual texts, offering procedures and types, ritual gestures, and iconography of different types of Divine images. These have all been preserved down to the intimate details, which give us a step-by-step record of how the netjeru are to be approached and venerated in Their Divine cultic temples. Something I should note is that while most Kemetics maintain some kind of shrine or sacred space for the veneration of Divine images and the presentation of offerings, the complex scale and sumptuousness of the ancient temples is a phenomenon relegated- for now- to the past. Kemetic priest/priestesshood does exist, and temple spaces are being established for the Kemetic Gods, but the scale of these spaces and the ritual observances taking place in them have been reduced considerably from those in existence in ancient times. However, there are still many simularities between modes of worship of the Sanātana Dharma and Kemetic traditions.

The mūrti is central to all places of worship in the Sanātana Dharma, whether in large temples or in private family shrines, and the procedures for maintaining and venerating mūrtis bears strong resemblance to the tradition of kau or sekhemu or cult images for the Egyptian Gods. In the Kemetic tradition, the cult statue, once enlivened through the correct ritual process, becomes the ka or visible aspect of the God, which is inhabited by the ba or spiritual essence of the God, making the image a tangible manifestation of the Deity's sekhem or power. For the Deity's essence and power to remain in the cult image, specific sacred acts and offerings must be presented to the sekhem perpetually (ideally every day), otherwise the Deity concerned will depart from the image and it will revert back to the status of inanimate object- meaning that the Deity's boons are no longer being transferred to the holy place or community via the tangible manifestation of the Deity's power on earth.

The experience of darśana in Sanātana Dharma certainly has correlations with concepts present in the traditional worship of the Egyptian Gods, and so too with the main elements of pūjā and āratī. Receiving darśana or a direct vision/sight of the Deity in Their mūrti is one of the primary aims of worship in Sanātana Dharma, which has an inner and outer, physical and spiritual meaning. In the worship of the Kemetic netjeru, the Daily Ritual performed for the Goddess or God is called Wen her, "uncovering (or revealing) the face", that is, disclosing the countenance or likeness of the Deity, which is either veiled or housed in a shrine with closing doors. The highlight of the Wen her is called ma'a netjer, literally "seeing the God", the moment the officiant actually beholds the God. But this is a two-way seeing, for just prior to seeing the God, the officiant makes a preliminary offering of purifying incense to appease the Cobra Goddess dwelling on the Deity's forehead; this is understood as being the dynamic protective power of the Deity which prevents the impure from having access to the Deity's physical presence. So there is an understanding here that the Deity is seeing the officiant of the Daily Ritual as much as the officiant is seeing the God. This is the most awe-inspiring and solemn moment of the entire ritual, and the officiant throws their body upon the ground in prostration before the majesty of the Deity.

One of the initial acts of the Kemetic Daily Ritual is the iret teka or making the torch, the striking of the Divine fire embodying the revelation of light on the two horizons at dawn, corresponding to the moment of cosmic creation when light pierced the darkness of the void for the first time. The presentation of the torch to the Deity fills not only the sanctuary with light, but also the material world with the light of creation, dispelling chaos and making way for the light-body of the God. This aspect of the ritual would correspond to the āratī for the devas of Sanātana Dharma. An elaborate series of purifications is carried out with incense, water infused with sacred natron-salt, and scented oils that resonates with the abhishekam and vibhūti/ kuṅkuma application. Kemetic deity images also receive adornment with necklaces and regalia corresponding to the alaṅkāram, and a series of food/beverage/flower offerings corresponding to the naiveydyam and mangalākshatān of Sanātana Dharma. In both traditions we find the bathing, anointing, ornamentation, and feeding of the Gods Who are spiritually present in Their material images, and both traditions have a very long, rich history of how Divine images are crafted, enlivened, and maintained in their respectice temple homes.

We cannot overlook the similarity in how the Gods of Kemet exit Their temples or shrines in processions, and how the devas in India are placed on Their vāhana mounts to emerge from Their temples during auspicious festival occassions. The traditional vehicles for transporting the Kemetic Deities on holy occassions are the wiau or boat-shrines, which were in ancient times elaborate replicas of divine boats made of wood and sheathed in gold and precious stones. The sekhem or cult image of the Deity was placed in a shrine in the center of the wia, which was then hoisted on the shoulders of priests who carried the boat in public processions. Though this sacred phenomenon is not being replicated in the present day exactly as it was, my own household maintains the tradition of taking the divine images of the Gods out on pilgrimage during festival times or on holy days. This is something that would obviously strike a chord with practitioners of the Sanātana Dharma, who are used to taking part in ecstatic celebrations where the mūrtis of their devas are taken on pilgrimage by the community.

A final observation here would be the similarity between how devotees of the devas and devotees of the netjeru develop fiercly loyal, loving relationships with their Gods, which are expressed in daily life in some surprising ways. Something I've noticed in both traditions is how even pop music songs, secular films, and experiences in the secular world can be received by devotees as signs or blessings or messages from their Gods. All Kemetics I've met have these types of relationships with the netjeru, which are based on very deep engagement with the Gods as living beings Who utilize the material world in ways that devotees will understand and respond to.

Top: Ptah-Sokar-Ausir Lord of the Secret Shrine, the Cobra-Goddess Wadjet on the Shrine of the Household Gods (below);

Why are westerners attracted to ancient Egyptian polytheism, and how can they approach its Gods in traditional ways? How is your work as an iconographer representative of that?

Ptahmassu Nofra-Uaa: Speaking from my own experience and connections with other Kemetics, it is the netjeru, the Goddesses and Gods of Kemet, that spark a deep fascination and move people to investigate ancient Egyptian religion- called Kemeticism by many of its adherents. I think this comes from some primordial reaction to the iconographic forms Egyptian deities take in ancient images people are exposed to at a young age through the mediums of film and blockbuster exhibitions of Egyptian artifacts. The bimorphic- half-human, half-animal- representations of the netjeru provoke strong reactions that nonetheless attract as very natural ways these Gods communicate the scope of Their powers, and these are forms that touch upon people's attraction to the natural world, to its creatures and what these animals embody. One might think that the very alien appearance of ancient Egyptian deities would work against westerners being drawn to Them, seeing as how everything about the netjeru is so far removed from the mainstream Christianity prevelent in the west, but it is by virtue of Their unusual forms in iconography that people are intrigued on a very deep level, which makes them want to understand why that fascination is there in the first place.

As I said before, Kemetics tend to be fiercely attracted to their Gods, loyal to Them because there is a powerful sense that these Gods want to connect, want to be present in the lives of human beings, and intervene directly in the lives of Their devotees. I think many Kemetics felt those things quite lacking in their experience of monotheism growing up, and so many Kemetics I've talked to express this conviction that their Gods manifest tangible signs and messages through daily life experiences, and this is definitely nothing new in the history of humankind's interaction with these Gods. The historical record is full of monumental inscriptions, letters, stelae, and ex-votos describing encounters with the netjeru through life events or boons granted by the Gods as an answer to prayers. Something the netjeru are not is removed from Their creation, distant from humankind, or unconcerned with the maintenance of the material world.

My work as an iconographer has evolved from a number of factors present in my spiritual life. The first of these comes from the nature of my Patron deity and namesake Ptah, Creator of the material world, the Gods, and all living things, and patron of painters and craftspeople. Something that tends to happen in Kemeticism is that devotees are attracted to the deities that embody the prominent characteristics present in themselves, so my attraction to Neb (Lord) Ptah was most natural for me because of who He is, and how He manifests the excellence of divine craftsmanship in the arts. In what has been referred to as the Memphite Theology, recorded on the monument known as the Shabaka Stone, it is said that the Creator Ptah gave form to all things by speaking them into existence, and that He placed the Gods in Their bodies of wood, stone, and clay; so it was the God Ptah Who created the divine images of the Gods, Their cult statues or idols, and established the worship of the Gods as it should be conducted by human beings.

Fundamentally, one of the most traditional ways Kemetics can come to their Gods is through the veneration of the netjeru in Their traditional iconographic forms. These are forms that have a tremendous buildup of power in them due to their continuous use as cult images over a period of more than five-thousand years, and the same can be said for the ancient prayers, hymns, and ritual texts offered to the Gods in worship. These are tools for proper religious engagement that Kemetics use to maintain the sacred threads of connection established by the Gods Themselves at the very beginning of recorded history. But the iconography of the Gods is quite significant in our worship because these are the actual forms the Gods entered when They first entered material forms, and these are the forms They are attracted to. Since our religious life is grounded upon our connection with the Gods as living beings, it follows that maintaining the presences of the Gods in sacred spaces is to our benefit, and the way we accomplish this is through the maintenance of the sekhemu or power-images, the cult images or idols, our mūrtis.

One of the most important aspects of my work is the actual ritual process I have assembled from ancient sources as the cultic framework sustaining each part of a God-image's creation. These are the prayers, hymns, ritual utterances and gestures, offerings, and pilgrimages accomplished for every stage of the work, which is executed in a highly controlled ritual environment where standards of divine purity are maintained throughout. The work I do is not decorative art or art expressive of my personal ideas or experiences, but is rather a divine framework for receiving the actual spiritual essence and powers of the Gods, Who possess or inhabit sekhemu as the beneficiaries of the Divine cult. This concept of Divine images is instantly recognizable to practitioners of Sanātana Dharma, who would never refer to a mūrti as a mere work of art, but understand that idols are awake with an interior life provided by the presence of the deva inside it.

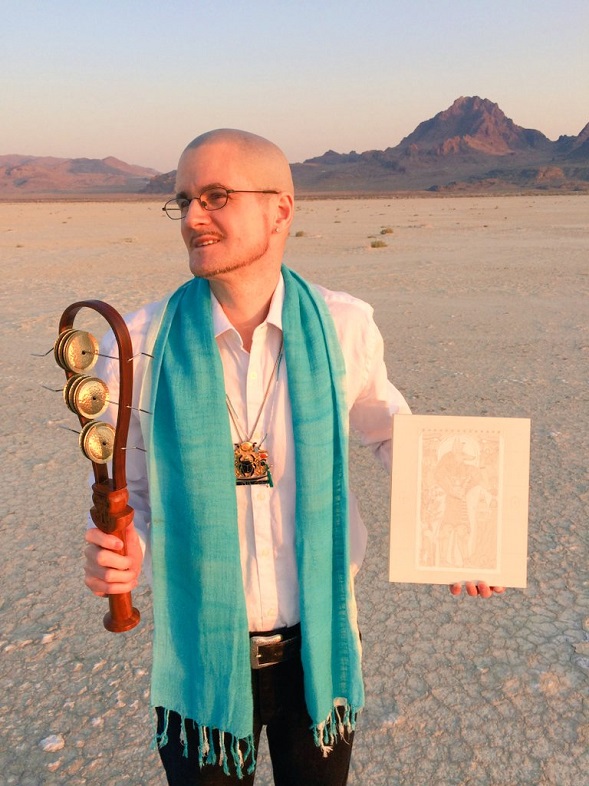

In the desert with the icon Anpu Lord of the Sacred Land in progress

What are the challenges to indigenous polytheism today? How can we preserve it?

Ptahmassu Nofra-Uaa: The biggest threat I see to indigenous polytheism is the missionary work of evangelical Christianity, which is just another form of colonialism; Christian organizations spending large sums of money to sustain the work of missionaries abroad, whose sole aim is to convert a populace from its indigenous traditions to Christianity. This is insidious, pervasive, and the most effective way to eliminate indigenous polytheisms from the face of the earth. There are any number of approaches one could take to heal the effects of this epidemic, but I'm going to answer this question from my own personal experience, from the point of view I have as a devotional polytheist and iconographer.

The strength of Sanātana Dharma in India is rooted in its strong religious communities, and these communities are sustained by their gurus and āchāryas, priestly traditions and ritual specialists. At the heart of this community network are the temples, and at the heart of the temples are the devas in Their mūrtis. It is India's intimate relationship with Her Gods that has sustained the power of the Dharma as a way of life passed down from generation to generation; these are the Goddesses and Gods Who have protected and nourished India from the beginning of history, and generated a line of enlightened teachers stretching down to the present day. Without its Gods, without its temple institutions, without its priestly traditions and ritual specialists, without the mūrtis that give a tangible home to the devas at the heart of religious communities, there is no hope for indigenous polytheism to continue in India. Indigenous religious communities can only be strong if their sacred institutions are strong, and their values are being supported by qualified teachers and specialists who carry out the worship of the Gods correctly. Correct worship of the Gods means establishing right relationship with the Gods through the activities required by the Gods in order to maintain Their bonds with a specific community. The maintenance of right relationship with the devas is essential for the legitimate operation of any temple, and a fully functioning temple is a requirement for carrying out the work of the Gods correctly. All of these things go hand in hand, and if any link in the chain is weak or functioning improperly, or missing altogether, the system will collapse.

What needs to happen for indigenous polytheisms to survive is a complete resistence to the spread of Christian evangelism by strengthening temple institutions and the religious specialists tied to those institutions. In the case of the Sanātana Dharma, this means the preservation of the temples and the resuscitation of defunct temples as the centers of community life and propagation of the Dharma. I was recently told by an Indian woman living in a small town in India that the once-thriving guilds of sacred craftsmen responsible for creating mūrtis were becoming lax in their specialist knowledge and devotion, and were beginning to disband. This is certainly a concern, because the creation of divine images according to strict ritual procedures is the only way a temple community can ensure the establishment and maintenance of right relationship with its gods. Without right relationship with the Gods, there is no divine life in a temple and no outpouring of boons as a result of sacred activities; so the crux of the matter is the preservation of the traditions responsible for sustaining religious communities the right way. This has to take priority for indigenous polytheism to survive.

Something I would like to see happen is the creation of some kind of support network- both online and offline- for sacred artisans, iconographers, and religious specialists of various polytheist traditions to share with one another, encourage one another's activities, and compile precious data concerning the materials, methods, and philosophies vital to the maintenence of right relationship with the Gods. Who is going to carry on these traditions in the next generation if this knowledge isn't preserved or prioritized for transmission? This means a willingness to cooperate and see traditions not as a luxury or cultural curiosity, but as a vital aspect of humankind's sacred development and relationship with its gods. Once this information is lost, it might be gone forever, and I know this only too well in the case of my own tradition because I am attempting to put back together the pieces of a very fragmentary puzzle in order to serve my Gods authentically and correctly. My work as an iconographer is grounded wholly in the purpose of establishing ties between the Gods and humankind, and to strengthen those ties through the correct ritual procedures and images. If our sacred relationships have any value, we must struggle to offer our best in each moment, and sustain our efforts not only for ourselves, but for those who come after us.

Idols representing forms of the God Ptah greet the sunrise in the Northwestern Utah desert, US

How does nature worship continue in these traditions? Is it among a minority?

Ptahmassu Nofra-Uaa: It is evident to me that India possesses a reverence for the Divine as expressed through the natural world that is virtually absent in the west. India has a very rich history of recognizing the powers of the devas in specific rivers, mountains, caves, and natural sites, and the experience of these is very much a part of the history of Sanātana Dharma as I have studied it. This kind of history exists in a similar way in Egypt in regards to the Nile River, the cataracts in the south, specific mountain peaks, and species of trees that were venerated by the ancient Egyptians as places where the Gods dwelt or places where the Gods were apt to demonstrate Their powers. One can see in the iconography of Egypt the predominant features of the natural world- plants and animals- utilized as embodiments of the Sacred, as manifestations of how the Gods transfer Their boons to the material world. These same features are very prominent in the Sanātana Dharma of India, which are also expressed in terms of pilgrimage to natural holy sites, such as the Gaṅgā Herself, Whose waters are venerated as being the divine source of purification from sin.

The majority of Kemetics today are practicing their faith outside a Nilotic context, which means that our sense of how the netjeru use the natural world to communicate Their presences to Their adorers has changed; because we are no longer in the physical environment native to our faith and its unique iconography. But something I've noticed in some Kemetics is the transference of the mindframe of sacred geography from a Nilotic to non-Nilotic context, as in seeing whatever natural environment they happen to live in as having qualities connected to specific gods- in a manner similar to how the ancient Egyptians viewed their landscape as sacred. This kind of transference of mindframe (which I call thinking Kemetically) is something I rely on heavily in my own spiritual practices and work as an iconographer. Since I live in the middle of the desert, in natural surroundings not unlike Egypt's Western Desert, it is easy for me to view the natural world around me through the ancient Egyptian lens that sees the mountains, sand, caves, and lonely stretches of barren land as imbued with the dynamic powers of the living Gods.

Through my work as a Kemetic priest, I have been able to recognize the patronage of specific deities resident in our landscape as local deities, and establish sites for pilgrimages and rituals where these deities may be venerated through Their traditional Kemetic rites. These are also places where the God-images I craft may be brought on pilgrimage to receive Divine empowerment, and absorb the sacred powers inherent to this holy landscape. Within this system I have developed over a period of many years, the veneration of nature is part and parcel of establishing right relationship with the Gods, Who move through nature without being subject to it or contained within it. The netjeru have always chosen specific plants, animals, and features of the natural world to demonstrate Their powers, and this includes rain, wind, storms, and changing weather patterns. These things show the human condition that the Gods are where we are, that They are living Powers that touch us directly and engage physically through the world we recognize as our own.

I would like to think that nature worship- veneration of the Sacred that transmits its boons through our natural landscapes- is not destined to be a passing footnote in the history of religion, especially when we consider how many of our natural resources we have destroyed because of our greed and shortsightedness. We have anihilated entire species, and laid waste to portions of our planet, which might in some cases be irreversible. There are some who feel, perhaps, that nature worship is part of superstitious practices that belong in the past, but something I recognize as the invaluable lesson of nature worship is the recognition of value beyond the human condition, that our earth and its species are our mother and father, the true custodians of our species, and the only chance we have for a future. What happens when we've decimated our planet and the delicate ecosystems that belong to it? Then we have murdered our own future. Sanātana Dharma has always championed the rights of the natural world by asserting the sacredness of all living things, not only human lives, but all life, all aspects of creation. From the smallest insects to the largest mountains, from massive river systems to seemingly insignificant streams, the Dharmic view is that these are sacred presences which require respect and preservation. Human beings are not the only precious lives.

Marigolds For Ganesha / I Offer At the Table of the Air by Ptahmassu K.M. Nofra-Uaa

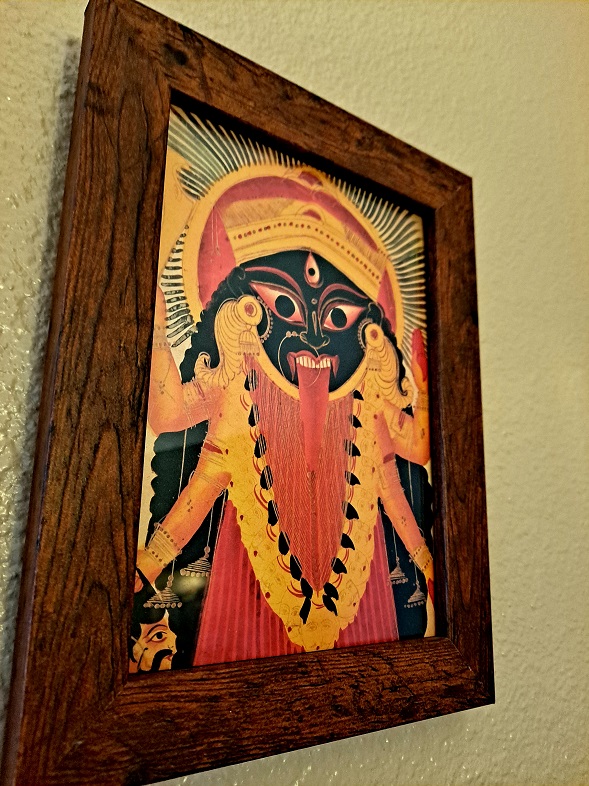

Who Has Summoned Me / Surely it is Mahendra By Ptahmassu K.M. Nofra-Uaa